Your Risk Model Is Your News Feed

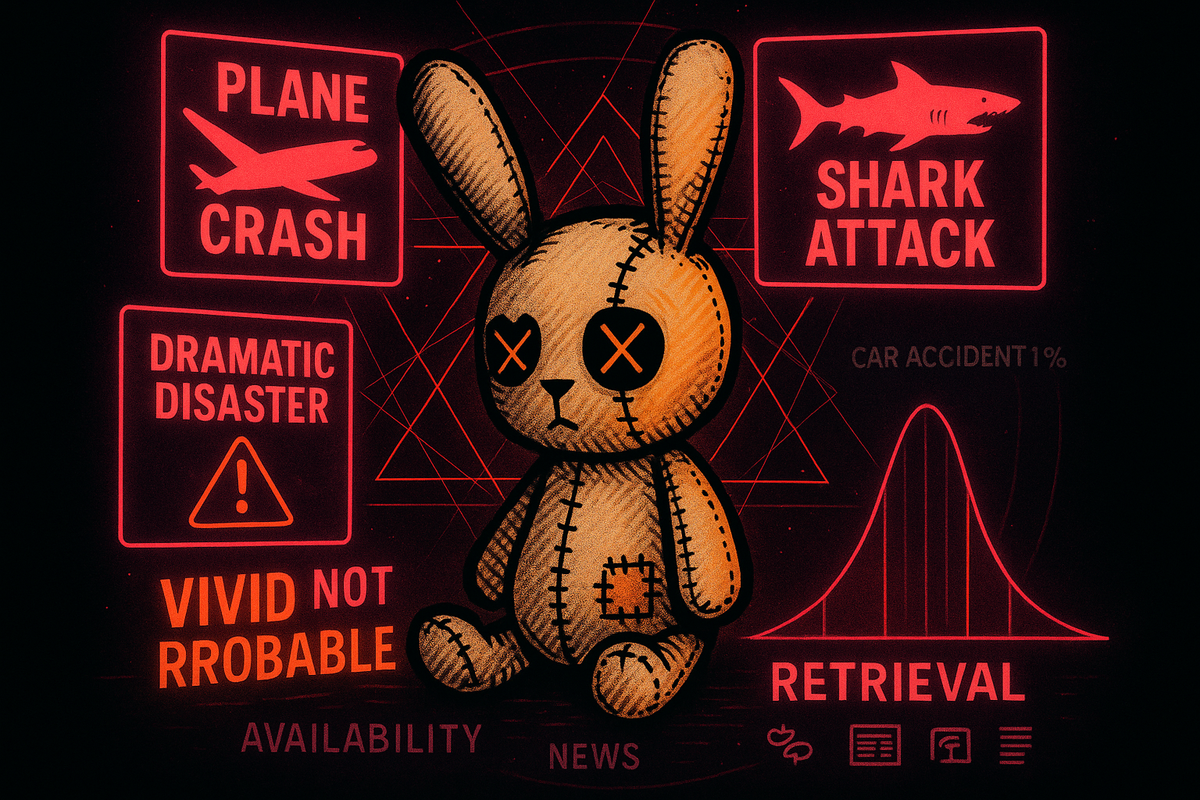

The availability heuristic makes your brain estimate risk by vividness, not frequency. Ask: Is this memorable because it's common, or because it's dramatic? The truly dangerous risks rarely make headlines.

Why plane crashes feel more dangerous than car accidents—and why your fear is a function of what you recently saw

You’re afraid of the wrong things.

Not because you’re stupid. Because you’re informed. Informed by a news environment that has no interest in calibrating your risk perception and every interest in capturing your attention.

The result: you worry about shark attacks and plane crashes while texting behind the wheel. You fear terrorist events and ignore heart disease. You obsess over rare catastrophes and sleepwalk through common ones.

Your brain is doing exactly what it’s supposed to do. And it’s getting the answer wrong.

The Shortcut

When your brain needs to estimate how likely something is, it doesn’t do statistics. It does recall.

How easily can I remember an example of this thing happening? How quickly does an instance come to mind? How vivid is the memory?

The easier the recall, the higher the estimated probability.

Psychologists call this the availability heuristic. Likelihood feels like fluency. If examples flow easily, the thing must be common. If you have to dig for examples, the thing must be rare.

This is fast. This is frugal. And in the environment your brain evolved for, this was remarkably accurate.

When It Works

Think about the ancestral environment. No newspapers. No internet. No global information network.

The only events you knew about were events you witnessed, events that happened to your tribe, or events memorable enough to become stories passed down.

In that world, availability was an excellent proxy for probability. If you could easily remember three people getting sick from those berries, those berries were probably dangerous. If attacks from the northern tribe came to mind readily, attacks from the northern tribe were probably common.

Your sample size was limited, but it was your sample—representative of your actual environment and the actual risks you faced.

Availability worked because memorable events were usually local events, and local events were the ones that mattered for your survival.

What Changed

Now you have access to every dramatic event on the planet.

A shark attack in Australia makes your news feed. A plane crash in Indonesia leads the evening broadcast. A terrorist attack in a country you’ll never visit dominates headlines for days.

Your brain processes these events the same way it processed local tribal information: as evidence about the world you live in, weighted by how easily they come to mind.

But the filter has changed catastrophically.

News is not a random sample of events. News is a curated selection optimized for attention capture. And what captures attention? The vivid. The dramatic. The rare. The visually spectacular. The emotionally activating.

The plane crash makes the news precisely because it’s unusual. If planes crashed all the time, it wouldn’t be newsworthy. But your availability heuristic doesn’t adjust for this. It just registers: plane crash, easy to recall, must be common.

Meanwhile, the car accidents that kill over 40,000 Americans every year almost never make national news. They’re too common. Too routine. Too boring.

So your brain encodes: plane crashes, easily available, high risk. Car accidents, hard to recall, low risk.

The reality is inverted. You’re about 95 times more likely to die in a car accident than a plane crash, mile for mile. But it doesn’t feel that way, because feelings are built from availability, and availability is built from media exposure.

The Mechanism

Here’s what’s happening computationally:

Your brain maintains something like a probability distribution over possible events. When you need to make a decision involving risk, you sample from this distribution.

But the distribution isn’t built from actual frequency data. It’s built from memory retrieval fluency. Events that are easier to retrieve get higher probability estimates.

What makes something easy to retrieve?

Recency. Events that happened recently are more available than events from years ago.

Vividness. Dramatic, visual, emotionally intense events are more available than mundane ones.

Personal relevance. Events that happened to you or people you know are more available than events that happened to strangers.

Narrative coherence. Events that fit a good story are more available than statistical abstractions.

News media optimizes for all four. Recent, vivid, pseudo-personal (“this could happen to you”), narratively satisfying. Your availability system lights up. The probability estimate inflates.

The base rate—how often this actually happens—never enters the computation.

Where This Costs You

Fear allocation. You spend emotional resources worrying about terrorism while underweighting heart disease, car accidents, and falls. The boring killers don’t make headlines.

Financial decisions. Whatever crashed recently feels like the biggest risk. After a market downturn, equity feels dangerous and cash feels safe—often at exactly the wrong time. Your risk assessment is a lagging indicator built from recent headlines.

Health anxiety. Rare diseases with dramatic presentations capture attention. After reading about a unusual diagnosis, you pattern-match every symptom. Meanwhile, the lifestyle factors actually killing people—diet, exercise, sleep, stress—are too boring to stick in memory.

Political reasoning. Vivid anecdotes overwhelm statistical realities. One dramatic story about a crime or a policy outcome lodges in memory and becomes “what’s really happening,” regardless of whether it’s representative.

Travel decisions. You avoid places with recent dramatic events while ignoring the baseline risks of staying home. Post-terrorist-attack tourism drops even when statistical risk remains negligible.

The Mismatch in a Sentence

Your brain estimates probability by asking: “How easily can I remember this happening?”

The modern information environment answers: “Here’s every dramatic thing that happened on Earth today.”

The result is a risk model calibrated not to reality, but to whatever your news feed decided was attention-worthy.

The Move

You can’t turn off the availability heuristic. It’s running below conscious access, shaping your intuitions before you’re aware of having them.

But you can ask a corrective question: Is this memorable because it’s common, or memorable because it’s dramatic?

If you’re estimating risk and the examples come easily—especially if they come with vivid imagery, emotional charge, and narrative structure—that’s a signal to distrust your intuition.

The boring risks are the real risks. Heart disease. Car accidents. Falls in the elderly. Metabolic syndrome. Depression. The stuff that doesn’t make headlines because it kills people quietly, routinely, uncinematically.

Your availability system can’t see them. But they’re what’s actually likely to matter.

When the news gives you something vivid to worry about, ask: “What’s the base rate?” How often does this actually happen, per capita, per year, compared to the mundane risks I’m ignoring?

The answer almost always recalibrates your fear in the right direction.

Toward the boring. Toward the probable. Toward the things that don’t come easily to mind—which is exactly why they’re the most important to remember.

This is Part 2 of Your Brain’s Cheat Codes, a series on the mental shortcuts that mostly work—and the specific situations where they’ll ruin you.

Previous: Part 1: The Roulette Wheel Has No Memory

Next: Part 3: The Dead Don’t Write Memoirs — Survivorship Bias