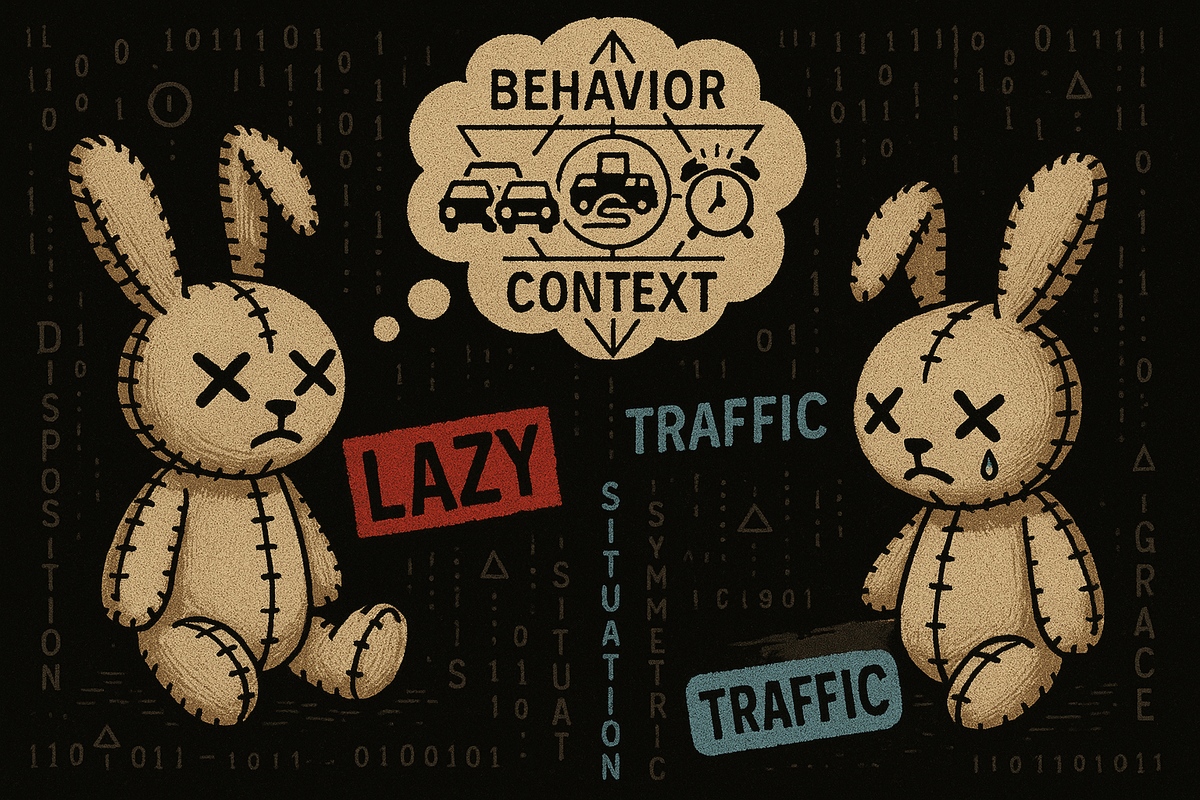

They're Lazy vs. Traffic Was Bad

You judge others by their actions but yourself by your intentions. This cognitive bias—the fundamental attribution error—damages relationships, careers, and understanding. Here's how to break the pattern.

Why you judge others by their actions but yourself by your intentions—and why this destroys relationships

Someone cuts you off in traffic. Asshole.

You cut someone off in traffic. Sorry, I was late for an emergency, didn’t see them, had to make that exit.

Same behavior. Different explanations. When others do it, it reveals their character. When you do it, it’s the situation.

This asymmetry has a name: the fundamental attribution error. And it’s quietly wrecking your relationships, your workplace, and your understanding of other humans.

The Error

The fundamental attribution error is the tendency to explain others’ behavior in terms of their character while explaining your own behavior in terms of your circumstances.

Someone is late → they’re unreliable. You’re late → traffic was bad.

Someone snaps at you → they’re rude. You snap at someone → you were stressed.

Someone fails → they’re incompetent. You fail → the task was impossible.

The error is fundamental because it shapes how you interpret almost all human behavior. It’s not a occasional mistake—it’s the default mode of social cognition.

Why It Happens

The asymmetry comes from information access.

When you act, you have full context. You know your intentions. You know the pressures you’re under. You know the situational constraints. You know that normally you wouldn’t do this, but given the circumstances…

When others act, you see the behavior. That’s it. You don’t see their internal experience. You don’t know their pressures. You don’t know they’re running on two hours of sleep, just got terrible news, are having the worst day of their year.

All you see is what they did. And behavior is easier to attribute to character than to invisible situational factors.

There’s also a cognitive efficiency argument. Inferring stable character traits is more useful than tracking every situational factor for every person. If someone is “rude,” you know what to expect. It’s a compression—lossy, but efficient.

The problem is that the compression throws away exactly the information that would generate empathy: the context that explains why someone is behaving this way right now.

The Actor-Observer Asymmetry

Psychologists call this the actor-observer asymmetry. When you’re the actor, you attribute your behavior to the situation. When you’re the observer, you attribute others’ behavior to their disposition.

You’re the actor in your own life. You have complete access to your intentions, your context, your mitigating factors. Of course your behavior makes sense given all that.

Everyone else you observe from outside. You see their actions, but not their inner experience. So their behavior seems to reflect who they are, not what they’re dealing with.

The asymmetry generates a world of generous self-interpretation and harsh other-interpretation. You are complex; they are their actions. You have reasons; they have personality flaws.

Where This Destroys Things

Intimate relationships. This is where the error is most destructive. Partners who make the fundamental attribution error interpret every transgression as evidence of character. “You forgot the milk” becomes “you’re inconsiderate.” “You didn’t text back” becomes “you don’t care about me.”

Research shows that happy couples do the opposite. They attribute negative behaviors to situations (“you’re stressed”) and positive behaviors to character (“you’re generous”). Unhappy couples reverse this: negative behaviors reveal character, positive behaviors are situational flukes.

Same events. Different attributions. Wildly different relationships.

Workplace conflict. A coworker misses a deadline. Your brain says: unreliable, uncommitted, probably lazy. But they might be underwater on three other projects, dealing with a family crisis, or blocked by another team’s failure.

The attribution shapes your response. “They’re unreliable” leads to distrust, micromanagement, resentment. “They’re overwhelmed” leads to support, assistance, problem-solving.

Political polarization. People on the other side of political issues are seen as morally defective, stupid, or malicious. Their positions reveal their character. Your positions, of course, are reasonable responses to the facts as you understand them.

It’s much harder to hate the other side if you attribute their beliefs to the information environment they’re in, the communities they’re part of, the experiences they’ve had—rather than to innate stupidity or evil.

Management and leadership. Managers who make the fundamental attribution error treat underperformance as a character issue. “They’re not smart enough” or “they’re not motivated.” Better managers ask: “What situational factors are causing this? What support, resources, or obstacles are involved?”

The first approach blames. The second approach solves.

The Mechanism

Here’s the computational story:

Behavior is visible. Situations are mostly invisible. Character is a stable summary that lets you predict future behavior.

So your brain does what’s efficient: it infers stable traits from observed behavior and uses those traits to predict. This is fast and often useful. Character traits exist, they do predict behavior, and inferring them from observation is reasonable.

The error is in the weighting. Situations explain more variance in behavior than traits do. People are more variable across contexts than the fundamental attribution error assumes. The same person can be kind in one setting and cruel in another, not because they’re “really” one or the other, but because situations pull different behaviors out of people.

But situational factors are invisible, so they get underweighted. What you see is behavior. What you infer is character. The gap between observed and inferred is filled in by the fundamental attribution error.

The Move

You can’t eliminate the error. The asymmetry is built into the structure of experience—you always have more context for yourself than for others.

But you can compensate:

Extend the grace you give yourself. When someone behaves badly, ask: “What would I have to be going through to act that way?” There’s probably an answer. Maybe they’re having their worst day. Maybe they’re carrying something you can’t see.

Assume context you can’t see. Before concluding someone is rude, inconsiderate, or incompetent, ask: “What situational factors might explain this?” The answer isn’t always exonerating—sometimes people really are assholes—but it’s often more illuminating than immediate character judgment.

For important relationships, ask. Don’t infer—inquire. “That was unlike you. What’s going on?” treats the behavior as data to be understood rather than a verdict on character.

Apply the asymmetry consciously. When you’re about to make a character attribution about someone else, try attributing it to situation first. When you’re about to make a situational excuse for yourself, try attributing it to character. See if the forced inversion reveals anything.

The fundamental attribution error turns complex humans into flat caricatures. They’re not rude—they’re struggling. They’re not lazy—they’re overwhelmed. They’re not malicious—they’re frightened.

You know this about yourself. You know you’re more than your worst moments.

Everyone else is too.

This is Part 10 of Your Brain’s Cheat Codes, a series on the mental shortcuts that mostly work—and the specific situations where they’ll ruin you.

Previous: Part 9: Nobody Noticed Your Stain

Next: Part 11: Beginners Feel Like Experts — The Dunning-Kruger Effect