The Roulette Wheel Has No Memory

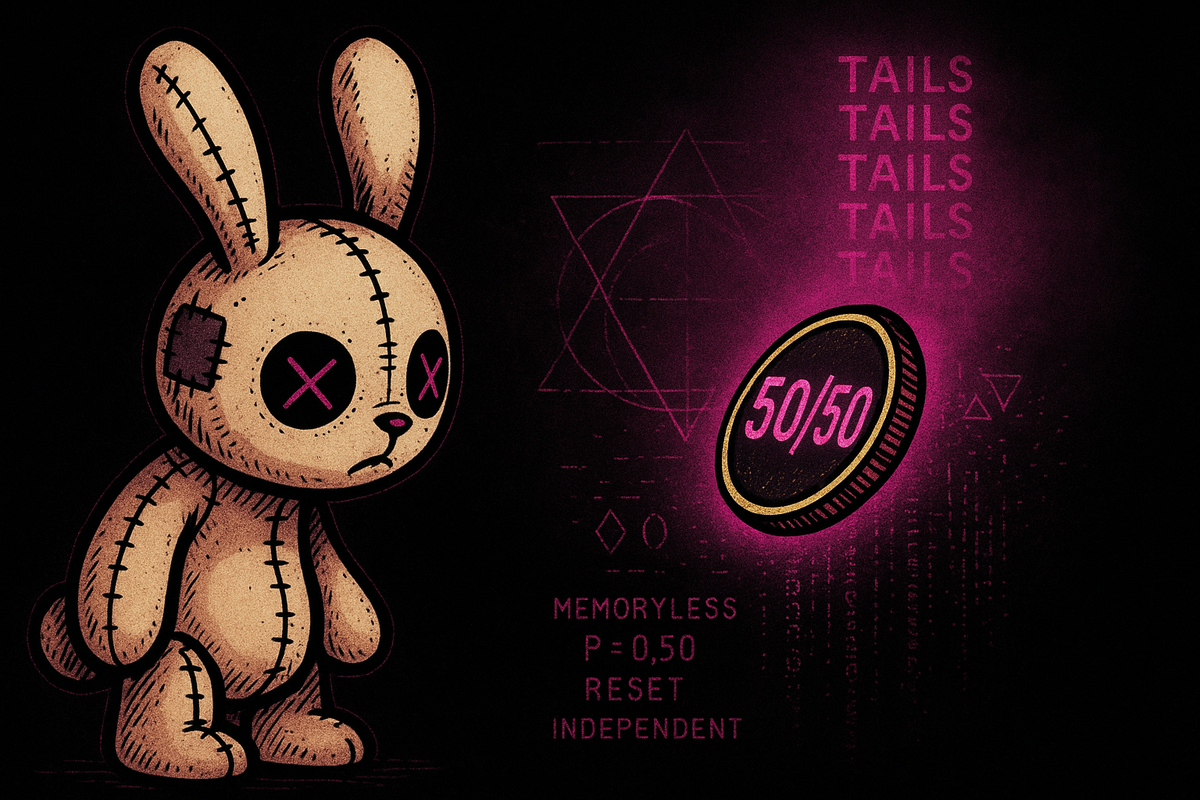

Our evolved pattern-recognition instincts systematically mislead us in memoryless systems. The diagnostic question: Does this system have memory?

Why your brain sees patterns in randomness—and when that instinct will ruin you

You’re at the roulette table. Not a casino person, maybe, but stay with me. Black has come up seven times in a row. You watch the wheel spin, the ball bounce, and something in your gut tightens.

Red is due.

You feel it. The universe owes you balance. Seven blacks is a streak, and streaks end. You push your chips toward red, confident in the correction that’s coming.

The wheel doesn’t care. The ball lands on black again.

Here’s the thing: you weren’t being stupid. You were being human. Your brain did exactly what it evolved to do—and that’s the problem.

The Pattern Machine

Your brain is a pattern-completion engine. It’s arguably the thing brains are for.

For millions of years, your ancestors survived by detecting regularities in chaos. Seven identical animal tracks meant a herd went that way. Seven days of rain meant the wet season had started. Seven times the russling in the bushes preceded a predator meant get the fuck out of there.

Pattern recognition kept them alive. The ones who didn’t see patterns got eaten.

So here you are, heir to a hundred thousand generations of survivors, with a brain that compulsively finds structure in sequences. It sees seven blacks and screams: the pattern must break. Red is coming. Bet on the correction.

But the roulette wheel doesn’t know what happened before. It has no memory. Each spin is independent of every other spin. The ball doesn’t know it landed on black seven times. It doesn’t know anything. It’s a ball.

Your pattern-matcher is firing at noise.

What’s Actually Happening

The Gambler’s Fallacy is the belief that past random events influence future ones. It feels like probability should “balance out”—that a string of one outcome makes the opposite outcome more likely.

It doesn’t.

Here’s the math, stripped bare: A fair roulette wheel (ignoring the green zero for simplicity) has a 50% chance of black on any given spin. That probability is reset every single time. The wheel doesn’t accumulate debt. There’s no cosmic ledger tracking what’s “owed.”

After seven blacks, the probability of the next spin being black is still 50%. After seventy blacks—which would be extraordinary but not impossible—the probability of the next spin being black is still 50%.

Your gut screams that this can’t be right. Seventy blacks in a row? That’s insane. Surely red has to come up.

And here’s where the confusion lives: You’re conflating two different questions.

Question 1: What’s the probability of getting seventy blacks in a row before you start?

Answer: Incredibly low. About 1 in 2^70, which is a number so large it might as well be impossible.

Question 2: Given that you’ve already seen sixty-nine blacks, what’s the probability of the seventieth being black?

Answer: 50%. The past spins already happened. They’re not competing probabilities anymore. They’re history.

The sequence is unlikely. The next event is not.

When This Instinct Is Actually Correct

Here’s what makes the Gambler’s Fallacy so pernicious: in most of life, your instinct is right.

Streaks usually DO mean something. If your partner has been distant for seven days straight, something is probably wrong. If a restaurant has had seven bad reviews in a row, there’s likely a real problem. If your car has made that noise seven times, it’s not going to spontaneously fix itself.

In the world your brain evolved for, sequences carried information. Repeated events were usually connected. The seventh rustle in the bushes was caused by the same predator that caused the first six.

Your pattern instinct isn’t broken. It’s miscalibrated for a specific type of situation: systems with no memory.

Dice don’t remember their last roll. Coins don’t remember their last flip. Lottery balls don’t remember their last draw. Roulette wheels don’t remember their last spin. These are what statisticians call independent events—each one is causally disconnected from the ones before.

The problem is that memoryless systems are rare in nature but common in casinos. Your brain never needed to evolve protection against slot machines because slot machines didn’t exist in the ancestral environment. You’re running savanna software on Vegas hardware.

Where This Gets Expensive

The roulette table is the obvious example, but let’s talk about where this actually costs people money.

The stock market “correction” fallacy. The market has dropped for five days straight. It HAS to bounce, right? Surely the selling is overdone. Time to buy the dip.

Sometimes this is true—but not because five down days make an up day more likely. Markets aren’t roulette wheels; they have memory, sort of. But the Gambler’s Fallacy leads people to assume mean-reversion when what’s actually happening is a trend. Five down days might be the start of five hundred down days. The market doesn’t owe you a bounce.

The “hot hand” inverse. This one cuts both ways. If you believe streaks must end, you might sell a winning stock too early because you feel like its run “can’t continue.” Meanwhile, the stock was winning for real reasons—competitive advantage, growing market, strong management—that persist regardless of how many green days it’s had.

Lottery number selection. People avoid numbers that came up recently, as if the lottery balls remember and will therefore avoid repeating. They won’t. Every drawing is independent. The numbers that hit last week have exactly the same probability of hitting this week.

Trading the “reversion” that doesn’t come. Entire trading strategies are built on the assumption that extreme moves must reverse. Sometimes they do—but not because probability demands it. When they don’t revert, the losses can be catastrophic. Ask anyone who shorted Tesla because it was “obviously overextended” in 2020.

The Deeper Trap: “Unlikely” Feels Like “Impossible”

Here’s another layer to this. Even when you intellectually accept that each spin is independent, the Gambler’s Fallacy sneaks back in through your sense of what’s “reasonable.”

Eight blacks in a row seems so unlikely that it feels wrong. Like the universe shouldn’t allow it. Like something must be broken—the wheel is rigged, or your understanding of probability is flawed, or something.

But unlikely things happen constantly. At any given roulette table, eight-in-a-row sequences occur regularly—not to you specifically, but somewhere, to someone. Across millions of spins in thousands of casinos every day, the “impossible” happens all the time. You just happened to be watching when this particular improbability landed.

This is related to survivorship bias (Part 3 in this series). You notice the streaks that seem crazy. You don’t notice the thousands of unremarkable sequences that happen around them. The crazy streak feels significant because you’re paying attention to it. But the universe isn’t paying attention. The universe doesn’t track which sequences are interesting to you.

The Diagnostic Question

So how do you protect yourself from your own pattern-matching brain?

One question: Does this system have memory?

If the past physically cannot influence the future—if each event is causally independent—then your pattern instinct is lying to you. Trust the math, not the gut.

- Roulette? No memory. Each spin is independent.

- Blackjack? Slight memory—card counting works because removed cards change the deck composition. But the effect is small and carefully managed by casinos.

- Stock market? Complicated memory. Past prices influence future prices through momentum, sentiment, and technical trading. But not in the simple “what goes down must come up” way the Gambler’s Fallacy suggests.

- Your relationship? Memory. Patterns of behavior persist for reasons. Seven days of distance probably does mean something.

- Coin flips? No memory. Fifty-fifty every time, forever.

The instinct to see patterns is a feature, not a bug. It’s kept your ancestors alive for millions of years. But features have domains of applicability. Your pattern-matcher works beautifully in a world of connected events. It fails catastrophically in systems where events are independent.

The roulette wheel has no memory. The ball doesn’t know it should land on red. The cosmos doesn’t track what you’re owed.

And the next spin, like every spin, starts from zero.

Next: Your Risk Model Is Your News Feed — Part 2: The Availability Heuristic

This is Part 1 of Your Brain’s Cheat Codes, a series on the mental shortcuts that mostly work—and the specific situations where they’ll ruin you.

Next: Part 2: Your Risk Model Is Your News Feed — The Availability Heuristic