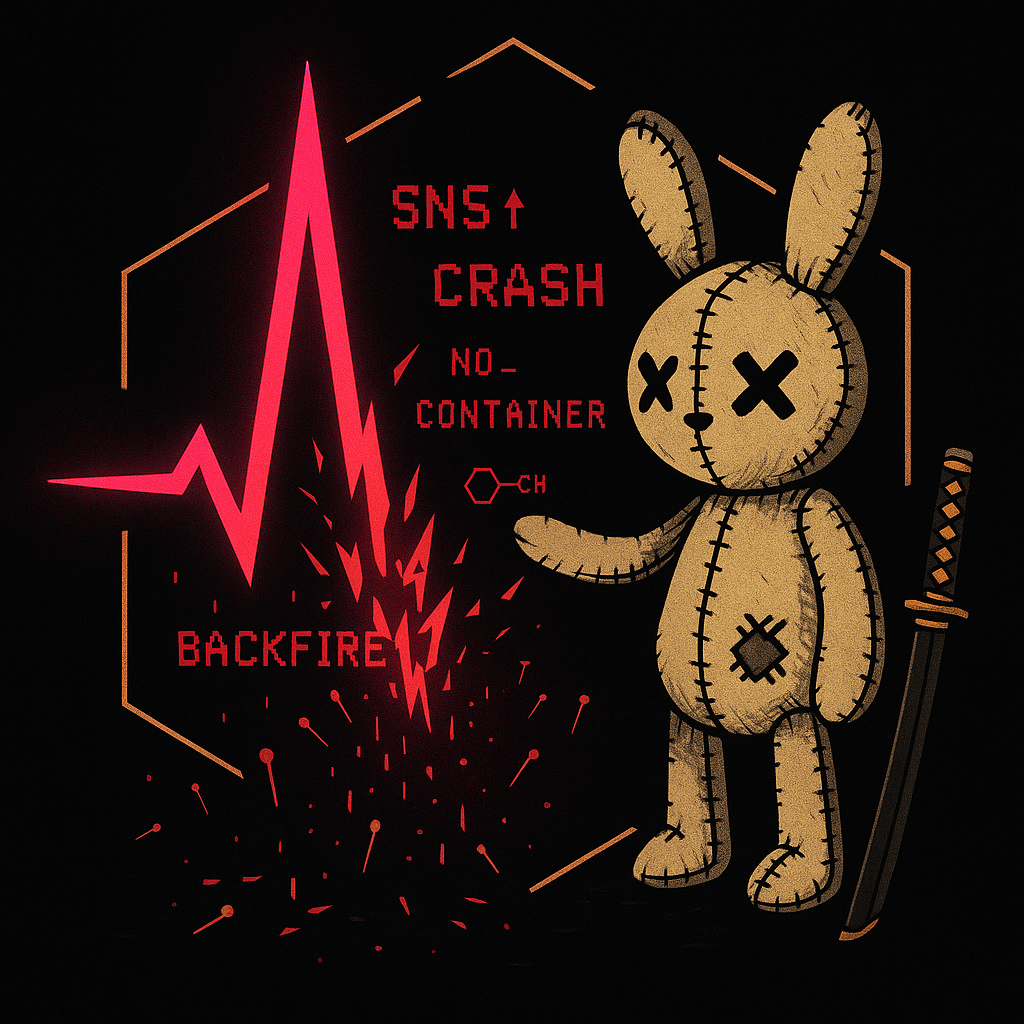

The Pleasure That Backfires

Sadists experience genuine hedonic spikes during aggression, followed by proportional crashes. Intensity requires negotiated boundaries to be sustainable.

Why Cruelty Feels Good (Until It Doesn't)

There's a particular kind of person who watches someone else get hurt and feels something light up inside them. Not guilt. Not empathy. Something closer to satisfaction.

We call this sadism, and we've been telling ourselves a comforting lie about it: that it's rare, that it lives only in prisons and psychiatric wards, that normal people don't carry this particular darkness. The research says otherwise. Sadistic tendencies exist on a spectrum that runs through the general population. The capacity to enjoy another's suffering isn't aberration—it's distribution.

But here's what makes this genuinely interesting, beyond the obvious horror: the pleasure is real, and it backfires. That's the finding from Chester, DeWall, and Enjaian's "Sadism and Aggressive Behavior: Inflicting Pain to Feel Pleasure" (Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2019; DOI: 10.1177/0146167218816327). Sadists experience more positive affect during the aggressive act—and more negative affect after. The hedonic spike is measurable. So is the crash that follows.

This isn't moral commentary. It's mechanism. And the mechanism reveals something important about why certain patterns of behavior persist even when they make us miserable.

The Pattern: Pleasure Contingent on Suffering

A team at Virginia Commonwealth University ran eight studies on this, total N of 2,255. They measured trait sadism and gave participants opportunities to act aggressively—noise blasts, hot sauce allocation, voodoo doll pins, the standard toolkit for studying harm in the lab without actually harming anyone.

The findings form a coherent shape:

Sadism predicted greater aggression across every measure. This held after controlling for impulsivity, poor self-control, trait aggression, and the full dark triad of Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy. Sadism isn't just psychopathy in a different hat. It's doing independent work.

The aggression wasn't purely reactive. Sadists didn't need provocation. They harmed innocent targets at the same rate as provocateurs—sometimes more. The usual situational amplifiers that make most people more aggressive barely moved the needle for sadists. They were already there.

And crucially: the pleasure was contingent on perceived suffering. When researchers manipulated whether participants believed their victim actually experienced pain, the sadism-pleasure link strengthened with perceived suffering and disappeared without it. The aggressive act alone wasn't rewarding. What lit up the reward circuitry was the knowledge that someone was hurting.

The Mechanism: A Scene Without a Container

To understand why this pattern exists and why it fails, you need to think about intensity and containment.

The nervous system doesn't distinguish cleanly between arousal states. Sympathetic activation—elevated heart rate, adrenaline surge, narrowed attention—feels similar whether it's coming from fear, anger, sexual excitement, or the thrill of dominance. What determines whether that activation becomes pleasurable or threatening is the container around it.

BDSM practitioners figured this out centuries ago. A scene can push participants into extreme autonomic states—states that would be traumatizing in an uncontrolled context—because the intensity is held within negotiated boundaries, explicit consent, safewords, and aftercare protocols. The container makes the intensity navigable. The exit makes the depth possible.

What the sadism research describes is intensity without the container. The hedonic spike during aggression is real—dopaminergic reward, the same circuitry that makes winning feel good and gambling addictive. But there's no negotiated boundary. No explicit consent from the target. No aftercare. No transition protocol to bring the nervous system back to baseline.

So the system crashes. The positive affect during aggression doesn't carry over. Instead, sadists show elevated negative affect afterward—and this holds even after controlling for baseline negative affect. The pleasure is borrowed from a future that arrives angry and wanting repayment.

The Geometry: Why the Middle Kills

There's a shape that keeps appearing across domains where humans seek intensity. Call it the barbell: extreme safety on one end, extreme intensity on the other, and a forbidden middle that looks moderate but is actually where you die.

In finance, Nassim Taleb made this famous: ultra-safe assets plus asymmetric bets outperforms the "balanced" 60/40 portfolio that quietly bleeds during normal times and collapses during tail events. The middle isn't moderate—it's where you take all the risk with none of the upside.

In sexuality, the barbell is safety-core plus intensity-peak. Secure attachment, established trust, clear boundaries, predictable repair—that's the anchor. And from that anchor, you can extend into edge experiences that would be destabilizing without it. The container enables the intensity. Skip the container, and the intensity becomes its own kind of violence.

The sadism pattern sits in the forbidden middle. It's seeking intensity—the research confirms the pleasure is genuine—but without the structural supports that would make intensity sustainable. No negotiation, no consent, no aftercare. Just the hit and the crash.

And like the gambler who keeps chasing the high despite the mounting losses, the pattern persists because the during-state feels good enough to override the after-state. The nervous system is optimizing for immediate reward, not integrated wellbeing.

The Feedback Loop: Why It Persists

The researchers note something important: sadists may "perceive aggression as an effective means to improve their mood, despite its contrary results."

This is the emotion regulation illusion. The same pattern shows up in revenge-seeking, substance abuse, compulsive eating, rage-scrolling. The behavior produces a short-term hedonic spike that the brain codes as "this worked." The negative aftermath gets attributed to other causes or simply forgotten by the time the next opportunity arises.

What makes sadism particularly sticky is that the reward is contingent on suffering—on the knowledge that you've actually hurt someone. This isn't a victimless loop. Each iteration requires a target, and each target's pain becomes the fuel for a pleasure that doesn't last.

The curvilinear finding is telling: the sadism-aggression link actually weakens at the highest levels of sadism. Even this "reward" has diminishing returns. The hit loses potency. The crash stays the same. The system runs itself toward exhaustion.

The Application: What This Means

If you recognize this pattern in yourself—the pleasure of cruelty, the attraction to others' discomfort, the jokes that cut too deep—the research offers a specific kind of clarity. The pleasure is real. You're not imagining it. And it's costing you more than it's giving you.

The nervous system wants intensity. That's not pathology—it's biology. But there are ways to get intensity that don't require someone else's suffering as fuel. The BDSM community has spent decades developing protocols for consensual intensity that doesn't crash the system. Athletes know this. Artists know this. Anyone who's pushed into a flow state knows that intensity and wellbeing can coexist—but only within the right structure.

The barbell applies: build the safety infrastructure first. Established trust, clear communication, explicit consent, repair protocols when things go wrong. From that foundation, intensity becomes sustainable. Without it, you're just chasing a high that leaves you worse than it found you.

The Shape Beneath

The sadism research reveals something that extends far beyond its specific subject. Pleasure without structure collapses. Intensity without container crashes. The hit is real, but the bill is realer.

This is the geometry of sustainable flourishing: not the elimination of intensity, but the construction of forms that can hold it. Safety isn't the opposite of excitement—it's what makes excitement possible without destruction.

The sadist's error isn't wanting to feel powerful. It's believing that someone else's pain is the only path to that feeling. The research shows exactly where that path leads: a pleasure that backfires, a high that crashes, a pattern that persists despite making everyone involved—including the sadist—worse off.

The nervous system is trainable. The same circuitry that lights up for cruelty can learn to light up for other things. But it won't happen by accident. It takes structure, intention, and the willingness to build containers before you chase intensity.

The pleasure is real. The backfire is also real. Choose your architecture accordingly.

—

Source: Chester, D. S., DeWall, C. N., & Enjaian, B. (2019). Sadism and aggressive behavior: Inflicting pain to feel pleasure. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(8), 1252-1268. DOI: 10.1177/0146167218816327