The Dead Don't Write Memoirs

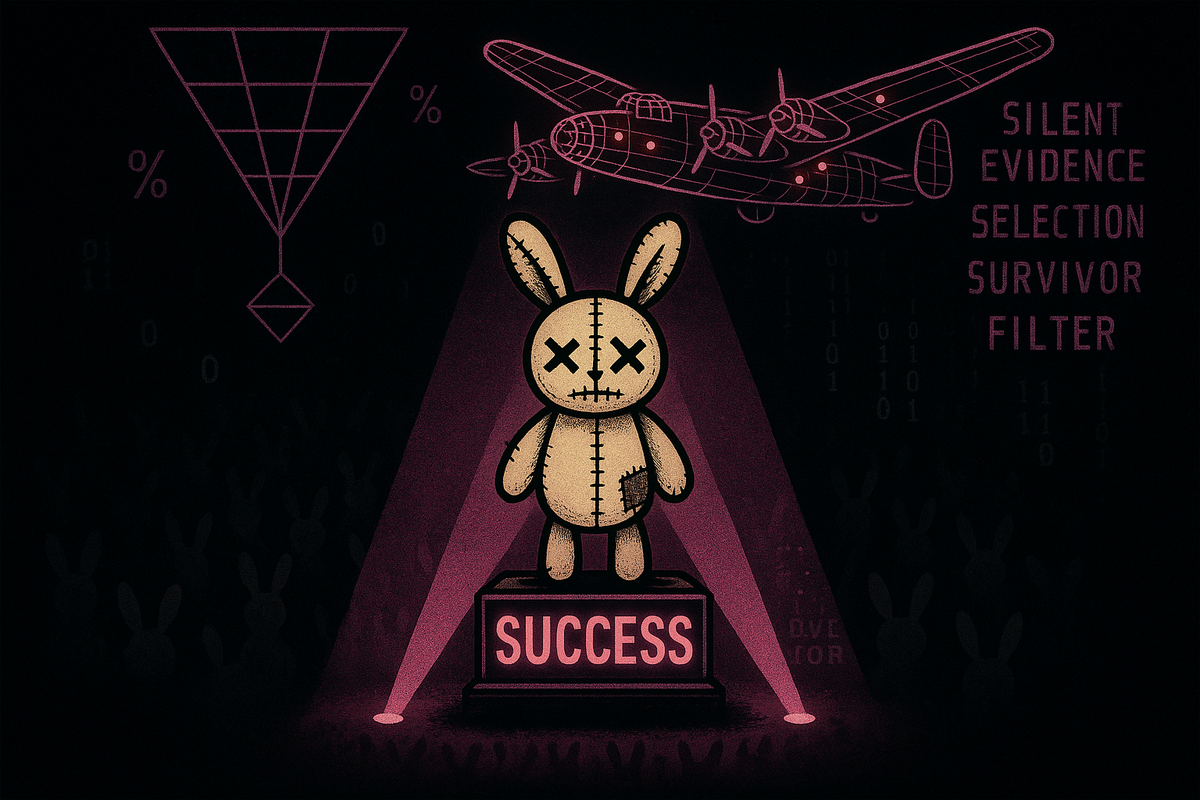

We build flawed mental models because our examples are pre-filtered to include only winners. Abraham Wald's WWII bomber analysis reveals how to spot the invisible data that changes everything.

Why you only hear from the winners—and why “college dropouts become billionaires” is a trap

Bill Gates dropped out of Harvard. Steve Jobs dropped out of Reed. Mark Zuckerberg dropped out of Harvard. The pattern is obvious: drop out of college, become a billionaire.

Except that’s insane.

For every dropout billionaire, there are tens of thousands of dropouts working jobs that don’t require a college degree, earning less, with fewer options. You’ve just never heard of them. They don’t give commencement speeches. They don’t write memoirs. They don’t get profiled in Forbes.

The winners are visible. The losers are silent. And your brain builds its model from the visible.

The Bullet Holes

The most famous illustration of survivorship bias comes from World War II.

Allied bombers were getting shot down at alarming rates. The military wanted to add armor, but armor is heavy—you can’t armor everything. So they studied the planes that returned from missions, mapping where the bullet holes clustered.

The data was clear: bullet holes concentrated on the wings and fuselage. The tail and cockpit had fewer holes. The obvious conclusion: armor the wings and fuselage, where the planes are getting hit.

Abraham Wald, a statistician, saw the error immediately.

The planes they were studying were the ones that came back. The bullet holes showed where a plane could take damage and survive. The places with no holes—the tail, the cockpit, the engines—those were the places where damage was fatal. Those planes weren’t in the sample. They were scattered across Europe in pieces.

The military was about to armor the wrong parts of the plane. They were looking at survivors and inferring what caused survival. But the survivors were survivors because they weren’t hit in the critical areas.

The missing planes were the data that mattered. And they were invisible.

The Pattern

Survivorship bias is what happens when you draw conclusions from a filtered sample without accounting for the filter.

The filter removes failures. What remains are successes. You study the successes and infer what made them succeed. But you’re missing the failures who did the exact same things and failed anyway.

The successful dropped out of college. But so did the unsuccessful—you just don’t hear about them.

The successful took a huge risk on a startup. So did thousands of others whose startups cratered.

The successful followed their passion. So did the people now struggling to pay rent.

Whatever pattern you find in the winners, you’ll also find in the losers. The difference between them might be luck, timing, network effects, or factors that have nothing to do with the visible pattern.

But the losers aren’t giving TED talks. The dead don’t write memoirs.

The Mechanism

Your brain builds models from available examples. That’s just how induction works—you see instances, you extract patterns, you generalize.

The problem is that your sample of instances is pre-filtered in ways you don’t see.

The filter might be: - Fame (only the successful become visible) - Media selection (only the dramatic stories get told) - Social proximity (you only know people who made it into your social sphere) - Survival itself (failed companies don’t have alumni networks)

The filter operates silently. You don’t experience it as a filter. You just experience “the examples I’m aware of.”

And from those examples, you infer rules: “Dropouts become billionaires.” “Following your passion leads to success.” “Risk-taking pays off.”

These rules might be true. They might be false. You can’t tell from the visible sample, because the visible sample is precisely the set that survived the filter. It tells you what survivors look like. It tells you nothing about the base rate of survival.

Where This Costs You

Career decisions. You model success by looking at successful people in a field. But you’re not seeing the much larger pool who entered that field and failed. Acting seems viable because you know famous actors. You don’t know the thousands who waited tables for years before giving up.

Investment strategy. You see the funds that beat the market over 20 years. You don’t see the funds that closed after 3 years of underperformance. The survivors look like geniuses. But if you flip enough coins, some sequences will look like skill.

Business advice. Successful founders write books about what they did. But many failed founders did similar things. Without seeing both groups, you can’t isolate what actually mattered versus what was incidental or even harmful but offset by other factors.

Historical reasoning. The civilizations you study are the ones that left records. The ones that collapsed completely, the ones that were conquered and erased—they’re underrepresented in history. You’re modeling “how civilizations succeed” from a sample that excludes the failures.

Health and longevity. You hear about the 95-year-old who smoked and drank daily. You don’t hear about all the people who smoked and drank daily and died at 60. One vivid survivor makes the risk seem lower than it is.

The Finance Version

This one is worth its own section because it’s expensive.

Mutual funds advertise their track records. But only the funds that survived long enough to have good track records are still around. The funds that underperformed got closed, merged, or quietly discontinued.

So when you look at “funds with 15-year track records,” you’re looking at the winners of a survival tournament. The losers aren’t in the sample. This makes the average visible performance look much better than the average actual performance of all funds that existed 15 years ago.

Studies estimate that survivorship bias inflates average fund returns by 1-2% annually in historical data. That’s enormous over time.

Similarly, when you backtest a trading strategy using historical stock data, you’re using a database of stocks that still exist. The companies that went bankrupt and got delisted aren’t in the data. Your strategy looks better than it would have performed in real-time, because you’re implicitly avoiding the catastrophic losses.

The technical term is “survivorship bias in backtests,” and it’s one of the main reasons strategies that look great in historical testing fail in live markets.

The Move

When you find yourself extracting a pattern from successful examples, ask: What would I see if the failures were visible?

The dropouts who became billionaires followed their gut. Would the dropouts who became baristas say the same thing?

The successful fund managers were concentrated and bold. Were the unsuccessful fund managers also concentrated and bold?

The visible pattern is real. The question is whether it’s causal or just correlated with being visible.

Here’s a heuristic: The more filtered your sample, the less you can trust pattern extraction. When you’re looking at a population that has been heavily selected—the famous, the successful, the survivors—assume that most of what you see is the selection effect, not the cause.

The dropout billionaires aren’t proof that dropping out helps. They’re proof that conditional on becoming a billionaire, dropping out didn’t hurt enough to prevent it. That’s a very different statement.

The dead don’t write memoirs. The failed don’t give advice. The silent majority is silent.

Any model built only from voices you can hear is a model of what it takes to be heard, not what it takes to succeed.

This is Part 3 of Your Brain’s Cheat Codes, a series on the mental shortcuts that mostly work—and the specific situations where they’ll ruin you.

Previous: Part 2: Your Risk Model Is Your News Feed

Next: Part 4: The First Number Wins — Anchoring