The Complexity Barbell: A Physicist Just Proved Why "Balanced" Strategies Fail

New arXiv research proves moderate positions are mathematically unstable. Sustainable advantage requires either stable simplicity or specialized complexity—never moderate mediocrity.

A paper dropped on arXiv last month that should terrify anyone running a "diversified" portfolio, a "balanced" career, or a "well-rounded" skill stack. César Hidalgo and Viktor Stojkoski, working out of Toulouse and Budapest, just published the mathematical proof that moderate positions are structurally unstable.

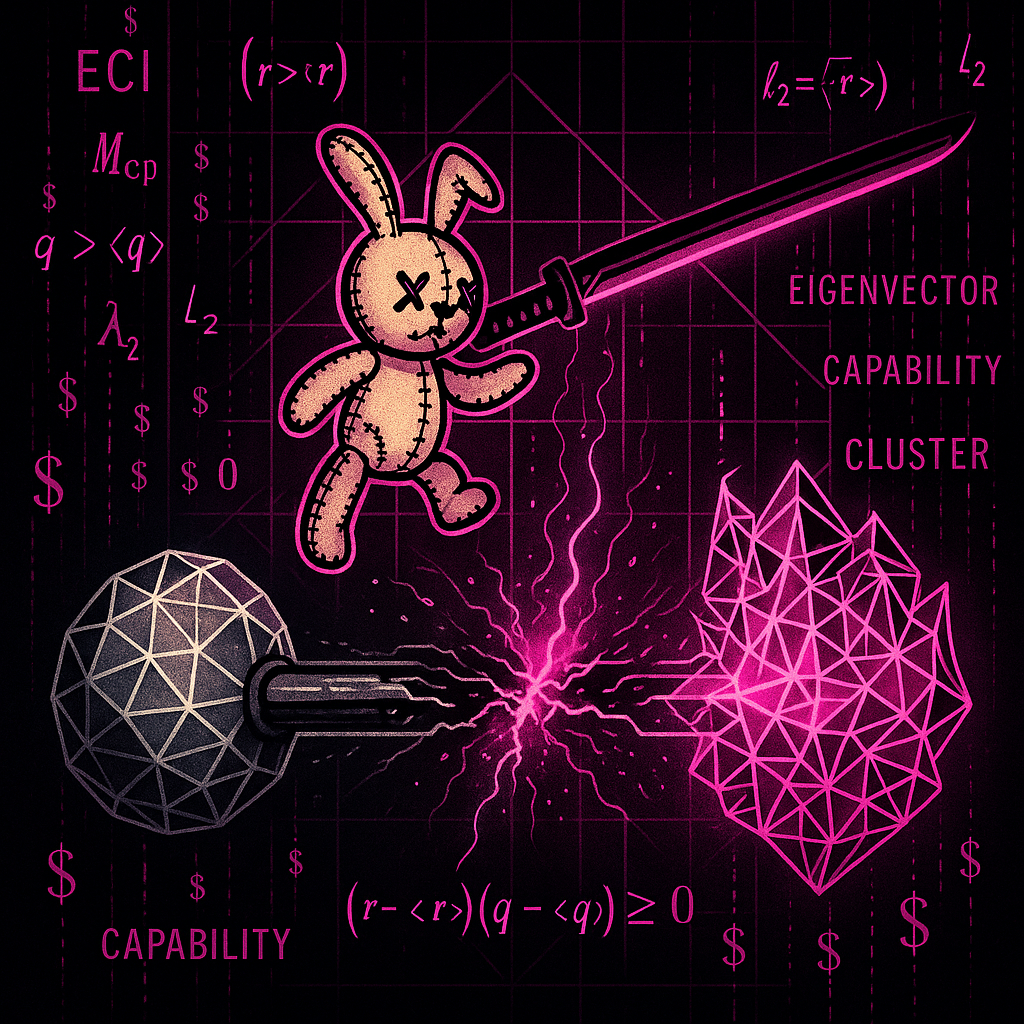

The paper is called "The Theory of Economic Complexity." It's 52 pages of linear algebra proving something Taleb has been screaming about for two decades: the middle gets competed out. Not sometimes. Not in certain market conditions. Mathematically. The geometry of capability-based production forces economies—and by extension, careers, portfolios, and organizations—into two clusters. High capability specializing in high complexity. Low capability specializing in low complexity. The moderate middle? It doesn't survive the eigenvalue decomposition.

This isn't metaphor. It's architecture.

The Setup

Economic complexity research has been around since 2009, when Hidalgo and Hausmann first proposed that you could measure an economy's "capabilities" without ever defining what those capabilities are. The trick was elegant: if two products tend to be exported by the same countries, they probably require similar capabilities. If a country exports many products that few other countries can make, it probably has lots of capabilities. You could infer the hidden structure from the visible pattern.

The method worked. The Economic Complexity Index they developed predicts GDP growth better than almost any other single variable. Countries converge toward an income level that matches their complexity score. The empirical results were robust. But the theory underneath was shaky. Why did this eigenvector method work? What was it actually measuring? Was it just a clever hack, or was there real structure underneath?

This new paper answers that question. And the answer has implications far beyond trade economics.

The Model

Hidalgo and Stojkoski start with a production function where output depends on capabilities. An economy produces a product if it has the capabilities that product requires. Simple enough. They model this probabilistically: economy c has capability b with probability r, and product p requires capability b with probability q.

The output matrix looks like this:

Y = A(1 - q(1 - r))

For multiple capabilities, you multiply these probabilities together. The more capabilities required, the more ways to fail. This is basically the O-Ring theory of development—the insight that complex production chains are only as strong as their weakest link, which is why rich countries make jet engines and poor countries make t-shirts.

But here's where it gets interesting. To connect this model to the empirical complexity metrics, they had to calculate something called the Revealed Comparative Advantage matrix—a normalization that shows what an economy specializes in relative to global averages. And when they worked through the algebra, a clean condition fell out.

The condition for specialization is:

(r - ⟨r⟩)(q - ⟨q⟩) ≥ 0

Read that carefully. An economy specializes in a product when both are on the same side of their respective averages. High-capability economies specialize in high-requirement products. Low-capability economies specialize in low-requirement products. Cross-quadrant positions—high capability in low-requirement activities, or low capability reaching for high-requirement activities—show up as non-specialization.

The world divides into two clusters. Not gradually. Not on a spectrum. Two clusters, separated by the average.

The Eigenvalue Truth

When they compute the complexity matrix from this specialization pattern and extract its eigenvectors, the second eigenvector—the one used to calculate economic complexity—does exactly one thing: it separates the high-capability cluster from the low-capability cluster.

In the single-capability model, it's literally a step function. ECI = 1 if you're above average capability. ECI = -1 if you're below. The intermediate values you see in real data come from having multiple capabilities with different distributions, but the fundamental structure remains: the eigenvector is a monotonic function of your average capability endowment.

And here's the result that should haunt anyone with a "balanced" strategy: diversity peaks below maximum complexity.

The most diverse economies—the ones specialized in the largest number of activities—are not the highest-capability economies. They're the ones slightly below the top. The truly high-capability economies specialize in complex activities, which makes them less diverse than moderately complex economies.

Diversification is a phase. You diversify on the way up. When you hit escape velocity, you specialize.

Why the Middle Dies

The paper doesn't just show that the middle is unpopulated. It shows why the middle is unstable.

Think about what happens in a world where capabilities compound. An economy with high probability of having any given capability has exponentially higher probability of having all the capabilities a complex product requires. If each capability has an 80% probability, a 10-capability product has a 10.7% chance of being producible. If each capability has a 40% probability, that same product has a 0.01% chance.

The capability function is multiplicative. Small differences in the underlying probability create enormous differences in the output space. This is fat-tail dynamics applied to production.

Now imagine you're a moderately capable economy trying to compete. You can't make the complex stuff—the probability math kills you. But you also can't compete on the simple stuff, because low-capability economies with lower wages can undercut you. You're stuck in the middle, where the margins are thin and the competition is fierce.

The paper formalizes this with wage dynamics. In equilibrium, wages are proportional to capability endowment. Economies out of equilibrium experience pressure to adjust. If your wages are higher than your complexity justifies, you face downward pressure. If they're lower, upward pressure. The system has an attractor, and it's determined by your capability level.

You can't will your way to higher complexity wages. You have to actually accumulate the capabilities.

The Network Geometry

One of the paper's most striking results explains why different networks of related activities have different shapes.

The product space—the network connecting products that tend to be co-exported—has a core-periphery structure. Complex products cluster in a dense core. Simple products scatter around the periphery. This structure emerges naturally from correlated capability endowments: if economies that have capability A also tend to have capability B, you get a hierarchy. Some economies have everything. Some have nothing. The products requiring more capabilities cluster together because only the high-capability economies can make them.

But the research space—the network connecting academic fields based on citation patterns—has a ring structure. Physics connects to chemistry connects to biology connects to medicine connects back around. No dense core. No clear hierarchy.

The paper shows this comes from a different capability structure. Academic fields don't require a universal set of capabilities that some universities have more of. They require different capabilities. A molecular biologist and a polymer chemist need overlapping but distinct skill sets. The capability matrix is circulant rather than correlated—each field connects to its neighbors because adjacent fields share capabilities, but there's no global ranking.

Same model. Different capability geometry. Different emergent structure.

The Career Barbell

So what does this mean if you're not a country?

The math applies anywhere capability-based production meets competitive dynamics. Which is everywhere that matters.

Consider your career as an economy. You have capabilities—skills, knowledge, relationships, credentials. Activities—jobs, projects, roles—require certain capabilities. The same multiplicative logic applies: complex roles require many capabilities simultaneously, and your probability of qualifying drops exponentially with complexity.

The moderate career strategy—"be pretty good at several things"—puts you in the middle quadrant. You're competing against specialists in every domain. You don't have the depth to command premium rates on complex work. You don't have the cost structure to compete on simple work. You're the economic equivalent of a middle-income country: too expensive for low-value-add, too thin for high-value-add.

The barbell career strategy inverts this. One end: a boring, stable capability that pays the bills and never threatens ruin. The other end: a deep specialization in something complex enough that few can compete. The middle—being moderately good at moderately complex things—is exactly where the geometry predicts you'll get squeezed.

The paper even provides the mechanism for why this feels so frustrating. The wage equation shows that income converges to capability level. If you're earning less than your complexity justifies, you'll feel the upward pull. If you're earning more, the correction is coming. You can't fake complexity. The market eventually figures out what you can actually produce.

The Escape

The hopeful reading of this paper is that it shows a path.

Capability accumulation is possible. Countries do move up the complexity ladder. The product space research shows how: you acquire new capabilities by leveraging adjacent ones. You don't jump from t-shirts to jet engines. You move from t-shirts to textiles to industrial fabrics to technical materials to aerospace components, each step adding capabilities that share overlap with what you already have.

The career equivalent is obvious. You don't go from junior analyst to CEO. You build adjacent capabilities, each one requiring slightly more complexity than the last, each one adding to your cumulative probability of producing high-complexity output.

But the paper also shows why this is hard. The eigenvalue structure creates sticky equilibria. Once you're in a capability cluster, the dynamics tend to keep you there. Low-complexity economies stay low-complexity not because of bad luck but because their current capability portfolio predicts their future capability portfolio. Path dependency isn't a bug. It's the geometry.

Breaking out requires deliberately acquiring capabilities you don't currently use. It requires accepting lower returns in the short term to build the portfolio that justifies higher returns later. It requires understanding that diversification is a phase, not a destination—you diversify to build capabilities, then specialize to exploit them.

The middle is where you pass through. Not where you stay.

The Geometry Was Always There

Taleb has been making a version of this argument since Antifragile. The barbell strategy—safety at one extreme, risk at the other, nothing in the middle—was presented as a heuristic, a way to survive fat-tailed environments.

Hidalgo just gave us the production function that generates it. The barbell isn't a strategy. It's the shape that survives the capability geometry. Moderate positions get competed out because the math of multiplicative capability requirements creates two basins of attraction. You're either accumulating capabilities toward the complex end or you're not.

The same structure appears everywhere this geometry applies. Portfolios. Careers. Organizations. Relationships. Anywhere that complex outcomes require the simultaneous presence of multiple factors, the moderate position is unstable.

The paper runs 52 pages and includes more linear algebra than most readers will want to parse. But the punchline fits in one equation:

(r - ⟨r⟩)(q - ⟨q⟩) ≥ 0

You're either above average in a domain that requires above-average capabilities, or you're below average in a domain that requires below-average capabilities. The cross-quadrants don't stabilize.

The middle is where you pass through. Fast.

The barbell is the shape that survives the capability geometry. Same structure. Different substrates. The math was always there.