Long John Silver: The Redpill Savant Who Read Greene in the Bunk

Part 3 of 13 in the Black Sails: A Leadership Masterclass series.

Silver doesn't want power. That's what makes him terrifying.

He wants comfort. Safety. Maybe love, eventually. A place to settle down where no one's trying to kill him. These are modest goals. Reasonable goals. The goals of a man who just wants to survive long enough to stop surviving.

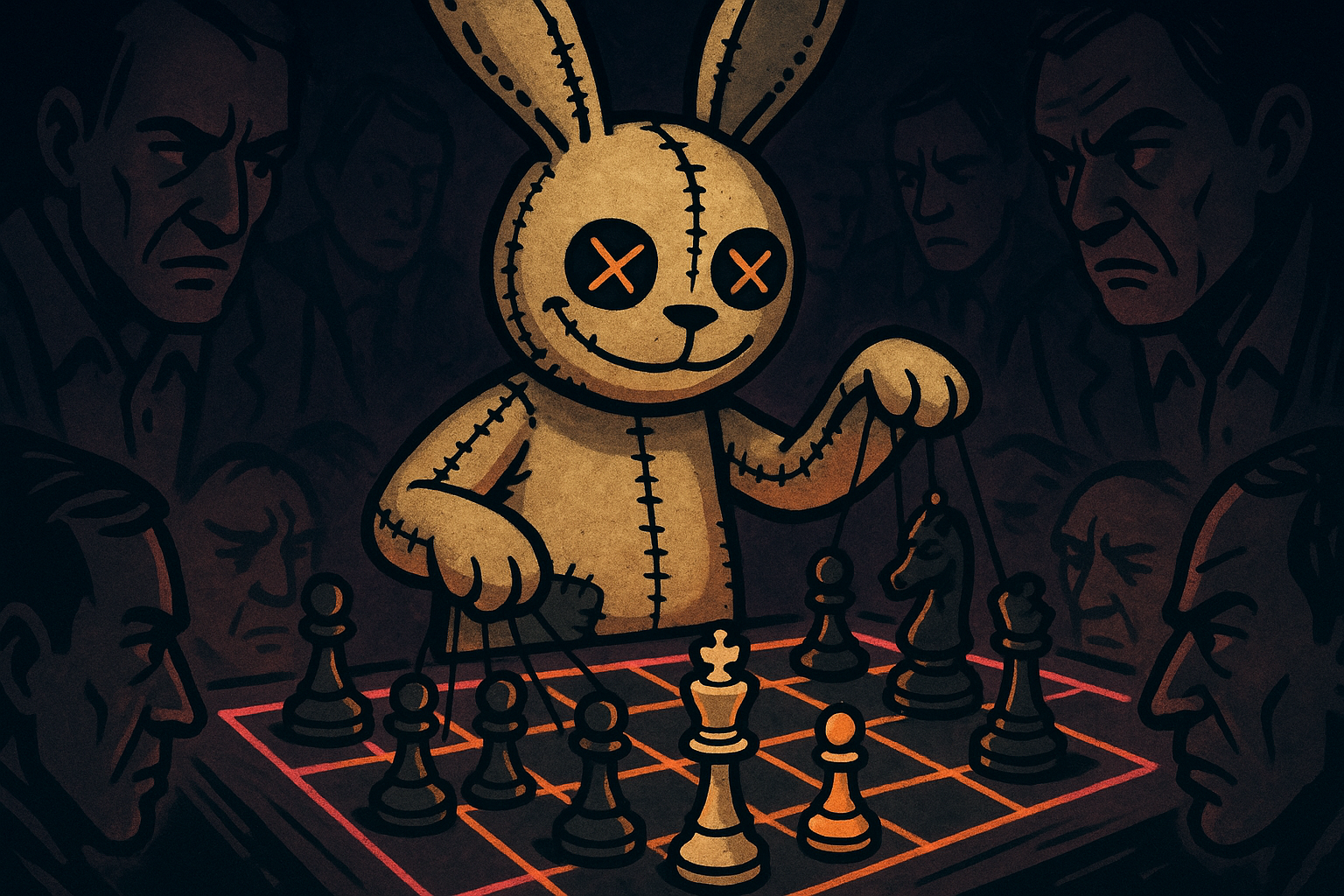

But he's so good at reading the room that power keeps accreting to him anyway. He sees the board. Everyone else is playing checkers while fixating on their pieces. Silver sees the whole game—who wants what, who fears what, which alliances are real and which are performance, where the fracture lines run, what happens next if no one intervenes.

He acquires power the way some people acquire debt: accidentally, incrementally, and then suddenly all at once.

By the end, the man who wanted nothing is the only one who got everything.

Let me tell you about Silver's starting position. It's important.

He arrives in Nassau with actually nothing. Not metaphorically. He's a liar who talked his way onto a ship, stole a page from a logbook he doesn't understand, and washed up in a pirate port with no money, no allies, no skills anyone values, and no plan beyond the next hour.

He can't sail. Can't fight. Can't navigate. He's bad labor at best. Known liar. The cook's assistant who talks too much.

Then he loses a leg.

In a world that runs on physical violence, he's at permanent disadvantage. He will never be the strongest person in any room again.

Four seasons later, everyone who started with advantages is dead, neutralized, or answers to him.

How?

Most origin stories start with hidden advantages. The protagonist seems disadvantaged but actually has secret wealth, or training, or connections. Silver has none of this. His disadvantages are real. The leg is gone. The skills don't exist. The reputation is negative.

What he has is one thing: the ability to read social dynamics better than anyone else in Nassau. Not charisma—Silver isn't particularly charming. Not manipulation—he's not a master schemer plotting ten moves ahead. Just accurate social perception. He sees what people want, what they fear, what they'll do to get the first and avoid the second.

This doesn't sound like much. In a world of swords and ships and treasure, reading the room seems like a parlor trick. But social dynamics are power dynamics. The person who sees them clearly can navigate them. The person who navigates them can eventually control them. Silver turns social intelligence into the only resource that matters: position.

Not through vision. Silver has no vision. No grand plan for Nassau, no ideology about freedom, no mission he's pursuing. When Flint delivers those stirring speeches about civilization's corruption, Silver's internal monologue is probably "can we speed this up, I'm hungry."

Not through force. He can fight if required—the crutch becomes a weapon, he adapts—but he's never the best fighter anywhere. The leg sees to that.

Not through resources. He controls no ships. Commands no crews. Holds no treasure.

Through reading the room.

Silver understands social dynamics the way mathematicians understand equations. He sees structure that others don't even know exists. He knows what you want before you've admitted it to yourself. He knows what you'll do to get it. He knows what you'll sacrifice to avoid losing something else.

He sees the whole game. You're playing your piece. He's playing the board.

Here's the thing about Robert Greene's 48 Laws of Power—people read it like a manual. Do these things, acquire power. Silver has never read Greene. Silver is Greene. The laws aren't instructions; they're descriptions of what Silver does naturally.

Never outshine the master. Silver makes himself useful to Flint. Necessary, even. But he never claims authority that would trigger Flint's defenses. He lets Flint be the visionary, make the speeches, take the captain's seat. Silver is the cook's assistant, the translator, the intermediary. Never the leader.

Until suddenly he is. But by then it's too late for anyone to stop him.

Get others to do the work. Silver rarely acts directly. He gives Flint information—Flint acts on it. He gives the crew perspective—they make choices based on it. He creates conditions where other people's natural moves serve his purposes. They're not being played. They're doing what makes sense. It's just that Silver built the situation they're making sense of.

Assume formlessness. Silver has no fixed position. No declared loyalty. No visible agenda. He shifts as circumstances shift. Flint is a hammer. Vane is a blade. Silver is water—flowing around obstacles, filling containers, finding cracks.

How do you fight someone with no fixed position? How do you predict someone with no visible plan?

You don't. You lose.

The mechanism behind this is threat modeling. Most people operate from fixed threat models: Flint sees everyone as either ally or obstacle to his war. Vane sees everyone as submission or resistance. These models make behavior predictable.

Silver has no fixed model. He assesses each situation independently. What do people want here? What do they fear? What moves are available? He doesn't bring predetermined answers. He reads the situation and adapts.

This makes him unpredictable—which makes him dangerous. You can prepare for the hammer. You can defend against the blade. You can't prepare for someone who changes shape based on what you're defending against.

But it also makes him exhausting. Silver is never off-duty. He's always reading, always adapting, always recalculating. The formlessness that makes him successful prevents him from ever resting. He can't relax into identity. He's always performing the next move.

The show stages a long conflict between Silver and Flint, and it's really a conflict between two operating systems.

Flint is the visionary. He has the mission, the ideology, the driving purpose. He will sacrifice anything—including himself—for the goal. This is his strength and his fatal flaw. The vision consumes him. When reality diverges from vision, Flint doesn't adjust the vision. He adjusts reality. Or tries to. Or burns things down trying.

Silver is the operator. No mission. No ideology. Just interests—and interests can be renegotiated. When circumstances change, Silver changes. When the terrain shifts, Silver shifts with it. He doesn't fight reality; he reads it and adapts.

In the end, the operator wins.

Not because operators are better than visionaries. The world needs people with missions. But visionaries are locked to their visions. They can't renegotiate. They can't adapt. When the vision becomes impossible, they break.

Operators just... continue. They flow around the new obstacle. They find the new opportunity. They survive.

Here's the tragedy: Silver doesn't want to win. He wanted to leave. Wanted to take Madi and disappear. Wanted out of the game entirely. But he was too good at playing it. His skills kept creating opportunities. Opportunities created obligations. Obligations created more opportunities. He got trapped in a success spiral he never wanted to enter.

This is the curse of competence. When you're good at something valuable, the world won't let you stop doing it. Silver is the best operator Nassau has ever seen. That skill is too valuable. Too many people need it. He can't exit without collapsing everything that depends on him—and by the time he realizes he's become load-bearing, extraction is impossible.

Flint chose his trap. Silver wandered into his. Both end up trapped. The difference is Flint knew he was choosing prison. Silver thought he was staying free and discovered too late that freedom requires being bad at things people need done.

Silver's ultimate move is beautiful in its simplicity: he becomes the voice of the crew.

Flint is the captain. Has the formal authority. Gives the orders. But Silver is the one the crew trusts. Silver speaks their language. Silver knows what they want. When Silver interprets Flint to the crew, they believe him. When Silver interprets the crew to Flint, Flint has to listen.

Silver becomes the interface.

Which means Flint can't move without him. Can't give orders without Silver translating. Can't maintain authority without Silver validating. The formal power is Flint's. The actual power is Silver's.

This is how operators work. They don't take the throne. They become the person the king can't king without.

The beauty of this position: plausible deniability. Silver never gives orders. He translates them. Never makes decisions. He explains them. Never claims authority. He validates it. This means he can't be held responsible. Can't be blamed. Can't be removed without collapsing the entire communication system that makes the ship function.

This is structural power rather than formal power. Formal power is visible—you have the title, the authority, the final say. Structural power is invisible—you're the layer through which all information flows, and information flow is what makes organizations work.

Flint has formal power. Silver has structural power. In any conflict between the two, structural wins. You can replace the person with the title. You can't replace the structure without rebuilding the organization from scratch.

By the time Flint realizes this, it's too late. Silver isn't his subordinate. Silver is the system. You don't beat the system by removing one node. You'd have to dismantle everything.

The final confrontation isn't a battle. It's a withdrawal.

Silver doesn't kill Flint. He doesn't have to. He just makes Flint's war impossible to continue. Withdraws the crew's support. Removes the resources. Reframes the narrative.

Flint is neutralized—not by violence but by politics. By the man who understood power better than the man who pursued it.

And Silver takes no throne. Doesn't want one. Never wanted one. He just wanted to be left alone, to live quietly with Madi, to stop fighting wars he didn't choose.

The reluctant king gets what he wanted—peace, love, exit—by winning a war he never entered voluntarily.

Here's the uncomfortable truth Silver teaches:

Power flows to the person who understands power, regardless of whether they want it.

You don't need the title. You need to be necessary.

You don't need the position. You need to understand all the positions.

You don't need to be the leader. You need to be the person the leader can't lead without.

Silver didn't pursue power. He pursued survival. But he was so good at surviving that everyone who pursued power lost to him.

The operators inherit the earth. Not because they're trying to. Because everyone else is too busy chasing things that don't matter to notice the guy without ambition who happens to see the whole board.

Previous: Captain Flint: The Founder Who Lies for the Mission Next: Charles Vane: Sovereignty as Leadership Style