Same Data, Different Decision

Identical information, opposite decisions. How frames set psychological reference points before conscious thought. Learn to spot manipulative framing in negotiations, medicine, and politics.

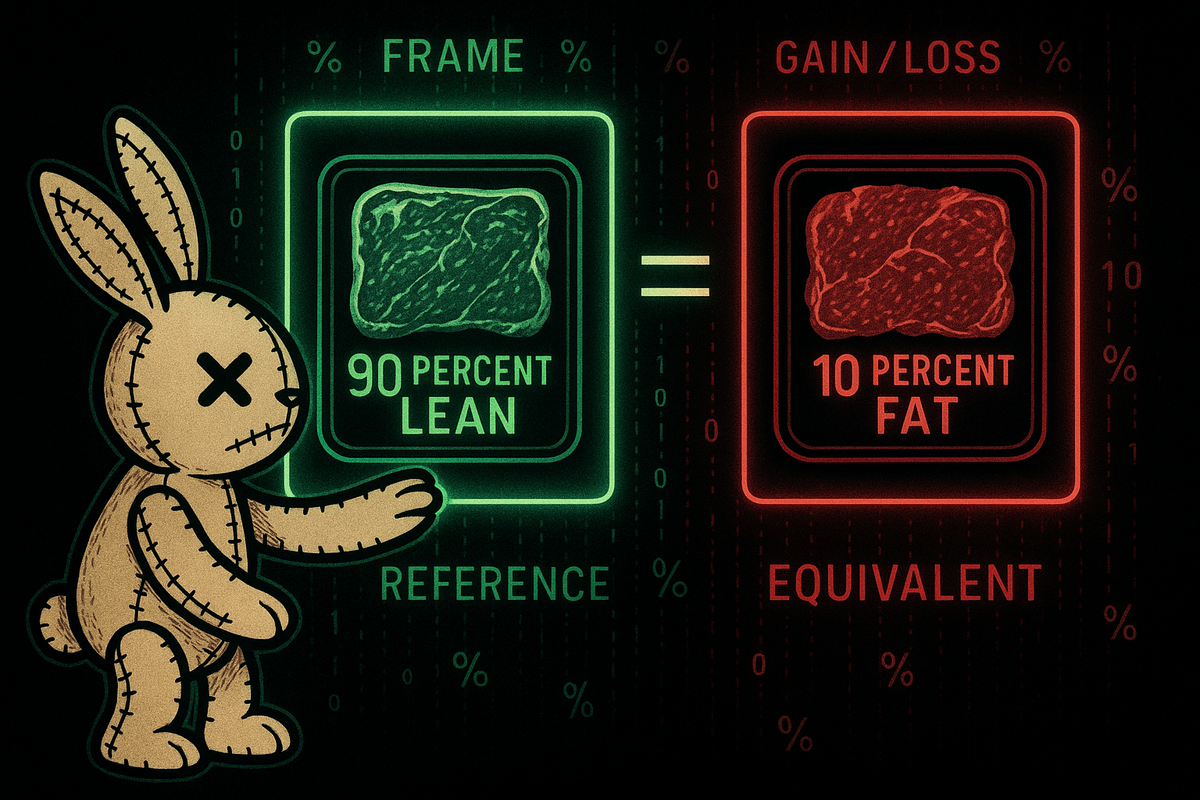

Why “90% fat-free” sells better than “10% fat”—and how presentation hijacks your choices

Two packages of ground beef sit on the shelf.

One says “90% lean.” One says “10% fat.”

Same beef. Same nutritional content. Same product.

But people reach for the 90% lean. They rate it as higher quality, healthier, more appealing. They’ll pay more for it.

Nothing changed except the frame. The information is mathematically identical. But the feeling is different, and the decision follows the feeling.

This is the framing effect. And it’s manipulating you constantly.

The Phenomenon

The framing effect is when the way information is presented—not the information itself—changes decisions and judgments.

Logically equivalent options produce different choices depending on whether they’re described in terms of gains or losses, positives or negatives, survival or mortality.

The classic demonstration comes from Kahneman and Tversky. They gave people a scenario about a disease outbreak:

Scenario A (gain frame): “Program A will save 200 people. Program B has a 1/3 chance of saving 600 and a 2/3 chance of saving no one.”

Scenario B (loss frame): “Program A will result in 400 deaths. Program B has a 1/3 chance of no deaths and a 2/3 chance of 600 deaths.”

These are the same outcomes. Program A saves 200 out of 600 either way. Program B is the same gamble either way.

But when framed as gains (lives saved), people preferred the sure thing—Program A. When framed as losses (deaths), people preferred the gamble—Program B.

Same options. Same outcomes. Different frames. Different choices.

Why It Happens

Framing exploits reference dependence. You don’t evaluate options in absolute terms. You evaluate them relative to a reference point.

The frame sets the reference point. “90% lean” sets the reference at fat-free, and 90% feels like almost there—a gain. “10% fat” sets the reference at no fat, and 10% feels like a loss from the ideal.

Once the reference point is set, loss aversion kicks in. You feel losses from the reference more intensely than equivalent gains. So the frame that emphasizes what you’re “keeping” (90% lean) feels better than the frame that emphasizes what you’re “getting” (10% fat), even though they’re identical.

This is automatic. Below conscious access. The frame shapes perception before you’re aware of perceiving.

The Shapes It Takes

Gain vs. loss framing. The most studied version. “Keep $30 out of $50” vs. “Lose $20 out of $50.” Same outcome, different feelings.

Positive vs. negative attribute framing. “95% success rate” vs. “5% failure rate.” Same surgery. Different levels of consent.

Risky vs. sure option framing. Gambling vs. sure thing preferences flip depending on whether options are framed as gains or losses.

Temporal framing. “$5 per day” vs. “$150 per month” vs. “$1,800 per year.” Same cost. Different psychological weight.

Relative vs. absolute. “Save 33%!” vs. “Save $5!” The percentage sounds better on cheap items; the absolute sounds better on expensive ones.

Anchored comparison. “Only $99!” (compared to an original price of $199). The $199 sets the frame; the $99 feels like a gain.

Where This Costs You

Negotiations. Whoever sets the frame controls the reference point. “We’re asking for a 10% reduction in your proposal” feels different from “We’re offering to accept 90% of your proposal.” Smart negotiators frame first.

Medical decisions. Surgeries presented with survival rates (positive) get more consent than surgeries presented with mortality rates (negative). Same data. Different decisions. Your doctor’s framing might be shaping your choices without either of you realizing it.

Financial products. “No annual fee” frames the baseline as having a fee and positions this card as a gain. “Low 2.9% interest” frames the baseline as higher interest. The frames are all designed to make the product feel better than neutral.

Political persuasion. “Tax relief” frames taxes as a burden being lifted. “Revenue cuts” frames the same policy as reducing resources. “Estate tax” sounds administrative; “death tax” sounds cruel. The frame carries the argument before any facts enter.

Personal relationships. “You always do this” frames current behavior as loss from an ideal. “I’ve noticed this pattern” frames it as observation. Same concern. Very different reception.

The Mechanism

Here’s the computational story:

Your brain doesn’t process raw information. It processes information relative to context. Context includes comparison points, expectations, and the linguistic frame.

This is actually efficient. Absolute evaluation is expensive—it requires knowing the full range of possibilities and your utility function across all of them. Relative evaluation is cheap—it only requires comparing to a reference point.

The shortcut is: evaluate relative to whatever reference point is available. This works well when reference points are meaningful. It fails when reference points are strategically chosen to manipulate you.

In the ancestral environment, frames were usually set by reality. The reference point for food abundance was recent experience of food. The reference point for danger was actual environmental threat.

Now frames are set by marketers, politicians, negotiators, and anyone else who benefits from shaping your reference point before you make a decision.

The shortcut hasn’t changed. The environment around it has.

The Move

You can’t perceive without a frame. That’s just how perception works. But you can swap frames.

When you’re about to make a decision, deliberately reframe:

Flip the valence. If it’s presented as a gain, describe it as a loss. If it’s presented positively, describe it negatively. “90% lean” → “10% fat.” Does your feeling change? That’s the frame talking, not the facts.

Ask: “What’s the reference point?” Every frame implies a baseline. What is this being compared to? Who chose that comparison? Is it meaningful, or was it selected to make this option look better?

Generate multiple frames. A raise of $5,000 is a 5% increase, $400/month, $100/week, $2.50/hour. Each frame creates a different intuition. Which intuition should you trust? Probably the one that matches how you’ll actually experience it.

Be suspicious of emphasis. When someone emphasizes certain information, ask what they’re de-emphasizing. The information they highlight is framed to help them. The information they minimize might be more important.

You can’t escape framing. Every description is a frame. Every presentation implies a reference point.

But you can choose your own frames. And sometimes that’s enough to break the manipulation.

This is Part 7 of Your Brain’s Cheat Codes, a series on the mental shortcuts that mostly work—and the specific situations where they’ll ruin you.

Previous: Part 6: Don’t Finish Bad Movies

Next: Part 8: Pretty People Seem Smarter — The Halo Effect