Pretty People Seem Smarter

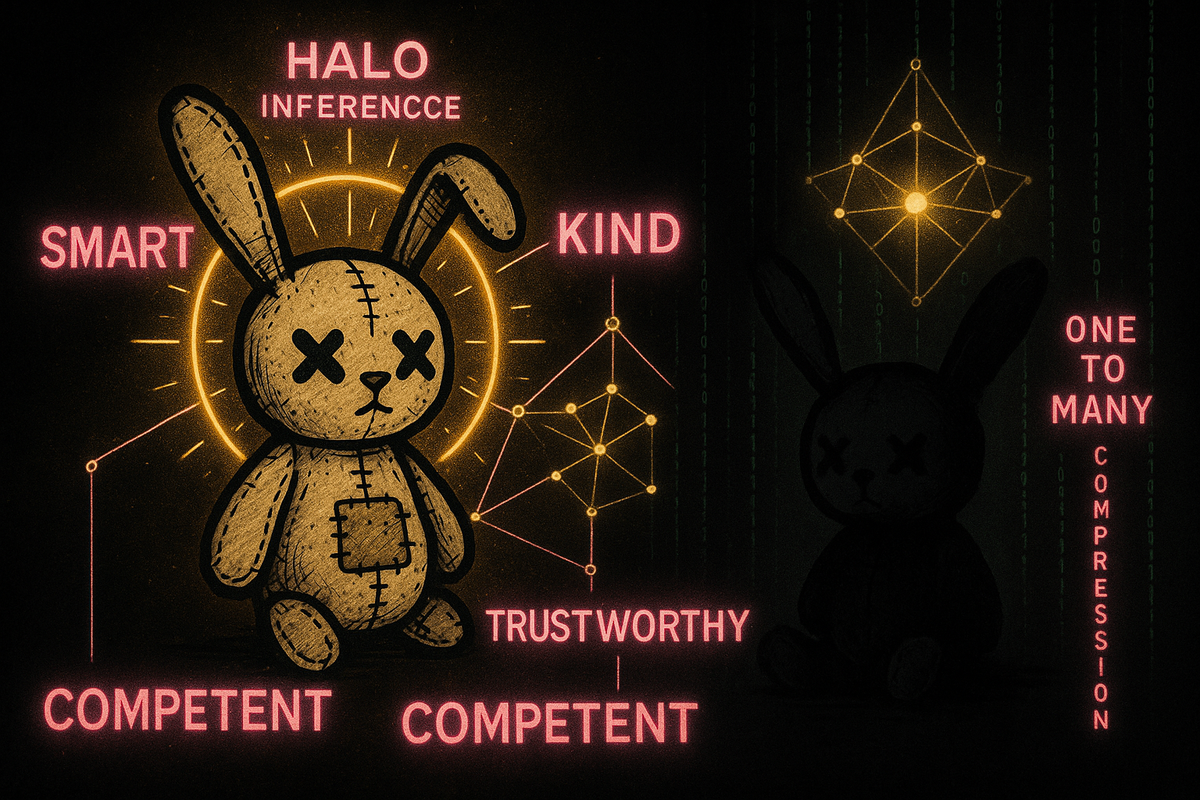

The halo effect makes one positive trait color everything else. Attractiveness creates false intelligence signals — and it's distorting your decisions right now.

Why one positive trait colors everything—and why first impressions are even more dangerous than you think

A defendant walks into a courtroom. She’s attractive—symmetrical features, well-dressed, put together.

Studies show she’ll get a lighter sentence. Not because judges are consciously biased toward pretty people. But because attractiveness activates a cascade of unconscious assumptions: she’s probably intelligent, probably kind, probably trustworthy, probably not the type to commit serious crimes.

One trait—physical attractiveness—has spread its glow across every other dimension of judgment. A halo effect.

And it’s warping your decisions every day.

The Pattern

The halo effect is when a single positive trait influences how you perceive everything else about a person.

It’s not limited to attractiveness. Any strongly positive (or negative) first impression can create a halo:

- Attractive → assumed to be smart, kind, competent

- Confident → assumed to be capable, trustworthy, successful

- Prestigious → assumed to be wise, ethical, correct

- Warm → assumed to be intelligent, skilled, honest

- Famous → assumed to be expert, qualified, insightful

The first strong impression becomes a lens through which all subsequent information is filtered. Positive traits assumed; ambiguous information interpreted charitably; flaws minimized or explained away.

The halo doesn’t just influence snap judgments. It persists. It resists contradictory evidence. It shapes how you process new information about the person for a long time.

Why It Happens

Humans are complicated. Learning everything about someone would take forever. Your brain takes a shortcut: sample one dimension, infer the rest.

This is dimensional compression. Instead of evaluating someone on twenty independent dimensions (intelligence, warmth, competence, honesty, creativity…), you evaluate on one or two salient dimensions and let them predict the others.

Evolutionarily, this made sense. In small groups with repeated interaction, people who were good on one dimension often were good on others. Traits correlated. Someone who was skilled, healthy, and socially adept probably was someone worth allying with.

The shortcut: if one thing is good, assume other things are good too. It’s fast. It’s frugal. And in environments with genuine trait correlation, it’s reasonably accurate.

What Changed

In the modern world, you encounter people outside any prior correlation structure.

The confident speaker might be incompetent. The attractive person might be cruel. The famous expert in one domain might have no expertise in others.

But your brain doesn’t know this. It sees one positive signal and generalizes, just like it always has. The halo lights up regardless of whether the underlying traits actually correlate.

Worse: people have learned to hack the halo.

Politicians hire image consultants. Executives take presentation coaching. Influencers optimize for exactly the signals that trigger halo effects—attractiveness, confidence, warmth—regardless of underlying substance.

The signals have been decoupled from what they used to signal. But the heuristic still fires.

The Inverse: The Horn Effect

The same mechanism works in reverse. One negative trait creates a “horn effect”—a spreading shadow that darkens everything else.

Someone who is unattractive, awkward, or low-status gets the opposite treatment: assumed to be less intelligent, less competent, less trustworthy. Ambiguous behavior is interpreted uncharitably. Achievements are attributed to luck or external help.

First impressions cut both ways. A negative first impression is as sticky as a positive one, and just as often wrong.

Where This Costs You

Hiring. Interviewers form impressions within seconds. If the first impression is positive—confident handshake, attractive appearance, warm demeanor—everything else is evaluated through that lens. Qualifications seem stronger. Weaknesses seem minor. The interview becomes a ceremony confirming the initial judgment rather than a genuine assessment.

Investing. Charismatic founders get funded. Confident pitches get capital. The halo around presentation obscures the business fundamentals. How many investors backed a charismatic vision that turned out to be hollow?

Leadership evaluation. When things are going well, leaders get halos—they’re brilliant, visionary, strategic. When things go poorly, the same leaders get horns—they’re arrogant, short-sighted, out of touch. The person didn’t change. The outcome changed the frame.

Relationships. Early attraction creates a halo that can persist for months or years. Red flags get dismissed. Concerning behavior gets rationalized. “They’re so smart/attractive/successful—surely they didn’t mean it like that.” The halo protects the image of the person against disconfirming data.

Expert evaluation. Famous experts in one field get assumed expertise in other fields. The Nobel Prize in physics creates a halo that makes their opinions on economics, politics, and nutrition feel weighty. But expertise is domain-specific. The halo generalizes illegitimately.

The Mechanism

Here’s the computational story:

Evaluating someone on every dimension is expensive. You don’t have unlimited time or attention. So your brain looks for predictive signals—traits that correlate with other traits you care about.

When you find a strong signal, you anchor on it and let it inform your other estimates. This is efficient. One good reading tells you something about the whole person.

The problem is that the inference is automatic and implicit. You don’t experience “I see she’s attractive, therefore I’ll assume she’s competent.” You just experience her as competent. The inference happens below awareness.

And because it’s implicit, it’s hard to check. The conclusion feels like perception, not inference. She doesn’t seem competent—she is competent. The uncertainty is hidden.

The Move

You can’t turn off the halo effect. First impressions will keep forming, and they’ll keep generalizing.

What you can do:

Name the trait that’s glowing. When you have a strongly positive impression of someone, identify the specific trait creating it. Is it their appearance? Their confidence? Their status? Their warmth?

Ask what else you’re inferring. Once you’ve named the glowing trait, ask: “What else am I assuming because of this?” Am I assuming they’re smart? Trustworthy? Ethical? Good at their job? Make the inferences explicit.

Check if the inferences are justified. Does attractiveness actually predict competence in this domain? Does confidence actually indicate capability? Does fame in one area translate to expertise in this area?

Often the answer is no. The inference is running on autopilot, generalizing from a trait that has no real predictive power in this context.

Delay important judgments. The halo is strongest in the immediate aftermath of the first impression. If you can wait—gather more data, observe more behavior, get independent assessments—the halo weakens and the real picture emerges.

Invert deliberately. Ask: “What would I think if this person were less attractive/confident/famous?” If the answer is “I’d be more skeptical,” that’s the halo talking. The skepticism is probably warranted.

First impressions lie. They feel like perception, but they’re projection.

Pretty people aren’t smarter. Confident people aren’t more capable. Famous people aren’t right about everything.

The halo is a lens. And sometimes you need to take it off.

This is Part 8 of Your Brain’s Cheat Codes, a series on the mental shortcuts that mostly work—and the specific situations where they’ll ruin you.

Previous: Part 7: Same Data, Different Decision

Next: Part 9: Nobody Noticed Your Stain — The Spotlight Effect