PART 4: Non-Ergodic Adoption

AI skill acquisition follows non-ergodic dynamics where delayed adoption creates permanent disadvantage. Early engagement triggers multiplicative capability gains that late adopters cannot recover.

The Prudent Mistake

“Wait and see” feels responsible. Let the early adopters hit the bugs. Let the hype cycle settle. Let best practices emerge. Then adopt—carefully, strategically, when the path is clear.

This is how sensible people approach new technology. It’s how you’ve approached most things in your career. And in most technological transitions, it’s exactly right. The patient adopter avoids the bleeding edge, skips the failed experiments, and enters when the cost-benefit is clear.

In this transition, it’s the riskiest position on the board.

Not because AI is special. Not because “this time is different” in the breathless way tech evangelists always claim. But because of a specific mathematical property that most people have never encountered—and that changes everything about how adoption timing works.

The property is called non-ergodicity. And once you understand it, “wait and see” stops looking prudent and starts looking like slow-motion ruin.

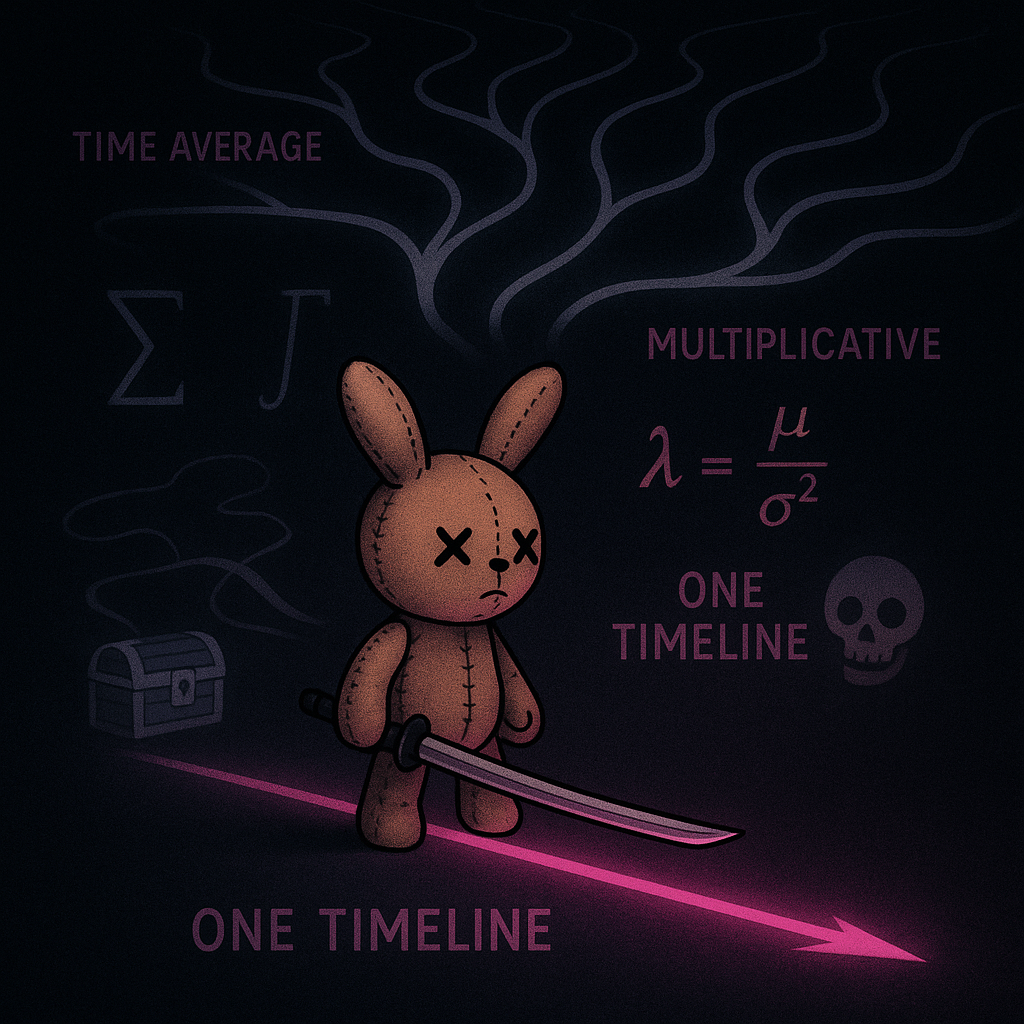

The Ergodicity Problem

Here’s a bet. You flip a coin. Heads, your wealth increases by 50%. Tails, it decreases by 40%. Expected value positive. Any economist would tell you to take this bet.

Take it repeatedly. Expected value says you should get rich. You won’t. You’ll go broke. Not unlucky-broke—mathematically certain broke.

How? Run the numbers. Start with $100. Win first (heads): $150. Lose second (tails): $90. You’re down 10% after one win and one loss. Win again: $135. Lose again: $81. Down 19% after two wins and two losses. The wins and losses are equal in number, but you’re losing—because wealth dynamics are multiplicative, not additive. You don’t add 50% and subtract 40%. You multiply by 1.5 and then by 0.6. And 1.5 × 0.6 = 0.9. Every round, you lose 10% regardless of order.

This is the ergodicity problem, identified by physicist Ole Peters and now published in Nature Physics. It’s not fringe theory. It’s a correction to a foundational error that economics has carried since the 1700s.

The error: assuming that the average outcome across many people (the “ensemble average”) equals the average outcome for one person across time (the “time average”). For some processes, these are equal. For multiplicative processes—which includes almost everything involving wealth, skills, and compounding—they catastrophically diverge.

Expected value calculations assume you can sample across parallel universes. Take the bet in a million parallel worlds, average the outcomes. But you don’t live in parallel universes. You live one life, in sequence, through time. Your outcome after bet one becomes the input for bet two. Losses compound against smaller bases. The sequence matters.

Ergodic process: Time average = ensemble average. Flipping coins for fixed dollar amounts. Sampling with replacement.

Non-ergodic process: Time average ≠ ensemble average. Flipping coins for percentages of current wealth. Almost everything that actually matters in life.

Here’s why this matters for AI adoption: skill acquisition is non-ergodic.

Skills Compound Multiplicatively

When you learn a new capability, you’re not adding a fixed unit of value to your career. You’re multiplying your existing capabilities by a factor. The new skill compounds on everything you already know. It opens doors that open other doors. It creates possibilities that create other possibilities.

This is why early career decisions matter so much—not because they’re inherently more important, but because they have more time to compound. A capability acquired at 25 has 40 years to multiply. The same capability at 55 has 10 years. Same skill, radically different lifetime value.

AI fluency is a multiplicative skill. It doesn’t add a fixed bonus to your work—it multiplies what you can produce, how fast you can learn, what problems you can solve. Someone who develops AI fluency now isn’t six months ahead of someone who starts in six months. They’re compounded ahead. Their fluency has been multiplying against everything they do, every project they complete, every adjacent skill they acquire.

This is the non-ergodic trap of “wait and see.” You’re not choosing between “adopt now” and “adopt later with same outcome.” You’re choosing between “start compounding now” and “start compounding later with permanently less time for the compounding to work.”

Every month you wait is not a month delayed. It’s a month of compounding you never get back.

The Time-Average Math

Let’s make this concrete.

Assume AI fluency provides a 20% productivity multiplier that itself grows 10% monthly as you get better. (These numbers are illustrative—the actual multiplier varies by domain. But the structure holds.)

Start now:

Month 1: 1.20x baseline

Month 6: 1.20 × (1.10^5) = 1.93x baseline

Month 12: 1.20 × (1.10^11) = 3.43x baseline

Start in 6 months:

Month 6: 1.00x baseline (still waiting)

Month 12: 1.20 × (1.10^5) = 1.93x baseline

By month 12, the early adopter isn’t 6 months ahead. They’re at 3.43x versus 1.93x—nearly twice the multiplicative output. And this gap keeps widening. The late adopter never catches up because they can never get those compounding months back.

This is why ergodicity matters. The ensemble average—“average outcome across all people who eventually adopt AI”—might look similar. But the time average—“your outcome, in your single timeline, given when you started”—diverges radically based on adoption timing.

Wait-and-see isn’t choosing a different path to the same destination. It’s choosing a permanently lower trajectory.

Ruin as Absorbing State

There’s a darker version of this math.

In non-ergodic systems, ruin is an “absorbing state.” Once you hit zero, you can’t recover. The game is over. And any strategy with non-zero probability of ruin, repeated enough times, approaches certainty of ruin.

Applied to careers: if your skills become obsolete faster than you can adapt, you don’t get to try again from the same position. The jobs you could have gotten are gone. The network you could have built has formed without you. The reputation you could have developed belongs to someone else. You can rebuild, but you’re rebuilding from a lower base against people who never had to.

This isn’t alarmism. This is the structure of non-ergodic competition. The cost of falling behind isn’t linear—it’s compounding and potentially absorbing.

“But surely I can catch up later if I need to?”

This is the ensemble-average fallacy speaking. Yes, in the abstract, people can learn new skills at any time. But you’re not “people in the abstract.” You’re one person on one timeline. Your later self will be catching up while your peers are compounding their lead. Your later self will be learning basics while others are developing advanced capabilities. Your later self will be entering a job market where AI fluency is baseline expectation rather than differentiating advantage.

The window isn’t closed. But the window has a different value at different times. And the value is declining.

The Kelly Criterion for Attention

If non-ergodic dynamics govern skill acquisition, what’s the optimal strategy?

The Kelly Criterion, developed for optimal bet sizing, tells us: allocate a fraction of your bankroll proportional to your edge. Never bet so much that ruin is possible. Never bet so little that you’re not capturing positive expected value.

Applied to attention and learning:

Your bankroll: Time and cognitive capacity available for learning

Your edge: AI’s leverage on your existing capabilities

The bet: Hours invested in developing AI fluency

Kelly says: the higher your edge, the more you should bet. AI fluency has asymmetric payoff—the downside is hours spent learning tools that might change, the upside is multiplicative amplification of everything you do. That’s a high-edge bet.

But Kelly also says: don’t over-bet. Don’t abandon your core capabilities to chase AI fluency exclusively. The stable core matters. The foundational skills that AI amplifies need to remain strong.

This is the neuropolar allocation from Part 3: 80% to stable core (the capabilities that compound, the judgment that guides AI use, the domain depth that AI leverages), 20% to adaptive edge (aggressive AI experimentation, learning by using, building with new tools).

The forbidden middle—10% here, a careful pilot there, wait for the enterprise version—fails the Kelly test. It captures neither the stability of committed expertise nor the compounding of early adoption. It’s the worst of both positions.

The Neuropolar Response to Non-Ergodicity

Non-ergodic dynamics reveal why the neuropolar stance is the only coherent response to this transition.

Stable core protects against ruin. If your identity, regulatory capacity, and foundational skills are solid, you can experiment aggressively without existential risk. A failed AI project doesn’t threaten who you are. A tool that doesn’t work out doesn’t collapse your value. The core is the floor you can’t fall through.

Adaptive edge captures compounding. By experimenting now—actually using tools, building with them, failing and iterating—you start the compounding clock. Every month of genuine practice multiplies against everything you learn next. The edge is where the multiplicative gains live.

Forbidden middle guarantees slow loss. The moderate position—some interest, occasional use, waiting for clarity—captures neither benefit. Not stable enough to provide identity security. Not aggressive enough to compound capability gains. Just slow drift toward obsolescence while feeling responsible.

The math doesn’t care about your reasons for waiting. Your timeline continues. The compounding continues (or doesn’t). The relative positions crystallize.

Practical Non-Ergodic Strategy

Given all this, what do you actually do?

Start the clock now. Whatever domain you work in, whatever tools are relevant, begin actual usage today. Not evaluation. Not research. Usage. The compounding doesn’t start until you’re actually practicing.

Accept early inefficiency. Your first months with AI tools will feel clumsy. You’ll be slower than your old methods. You’ll make mistakes. This is the dip every skill acquisition goes through. But on the other side of the dip is multiplicative capability. The people who quit in the dip never reach the compounding phase.

Protect the core while extending the edge. This isn’t either/or. Maintain and deepen your foundational capabilities—they’re what AI amplifies. But carve out protected time for aggressive experimentation. The 80/20 allocation is a guideline, not a prescription. Find your ratio and hold it.

Track trajectory, not position. In non-ergodic competition, where you are matters less than how fast you’re compounding. Someone “ahead” of you but stagnating will be passed by someone “behind” you but compounding. Focus on your learning velocity, not your current skill level.

Find compounding communities. Skills compound faster in environments where others are also developing them. The insights, the shortcuts, the failure patterns—all shared. This is why “learning in public” works. The community accelerates everyone’s compounding.

The Uncomfortable Truth

There’s no comfortable version of this math.

If non-ergodic dynamics govern skill acquisition—and they do—then the timing of adoption isn’t a preference or a personal choice. It’s a strategic variable with compounding consequences. “Wait and see” isn’t a neutral option. It’s an active choice with predictable outcomes.

This doesn’t mean panic. Panic is a nervous system state that prevents learning. It doesn’t mean abandoning judgment. Many AI tools are overhyped and not worth learning.

It means: understand what you’re choosing. Every month of waiting has a cost measured in compounding months not captured. That cost may be worth paying for specific reasons. But it should be a conscious choice, not a default.

The neuropolar stance isn’t about risk tolerance. It’s about understanding which risks are actually risky.

In a non-ergodic game, the biggest risk isn’t moving too fast.

It’s moving too slow and running out of time to compound.

This is Part 4 of Neuropolarity, a 10-part series on navigating the AI phase transition.

Previous: Part 3: The Neuropolar Stance

Next: Part 5: The Competence Vacuum — What happens when experts fail