Non-Ergodic Reality: Why Your Expected Returns Are a Lie

Ole Peters, the death of expected value, and the math that actually keeps you alive

Pillar: MONEY | Type: Pattern Explainer | Read time: 9 min

The Lie You Were Taught

Here's a bet. Flip a coin. Heads, you gain 50% of your wealth. Tails, you lose 40%. Expected value positive. A finance professor would tell you to take this bet. An economist would call you irrational if you refused.

Take it a hundred times. Expected value says you should be rich. You won't be. You'll be broke. Not unlucky-Loss—mathematically certain broke. The same calculation that says "take this bet" leads to ruin with probability approaching one.

This isn't a paradox. It's not behavioral bias. It's not about risk aversion or utility curves. It's a 300-year-old error at the foundation of how we calculate value—and Ole Peters, a physicist at the London Mathematical Laboratory, finally diagnosed it. Published in Nature Physics, not some heterodox blog. The error is fundamental, and correcting it changes everything about how you should manage money.

Expected value is a lie. Not sometimes. Not for some people. For everyone who lives a single life in sequential time.

The Pattern: Ensemble vs. Time

The error goes back to Daniel Bernoulli in 1738. He was solving the St. Petersburg paradox—a game with infinite expected value that no sane person would pay infinite money to play. His solution: people have diminishing marginal utility for wealth. They're "risk averse."

Bernoulli was wrong about why his solution worked. He got the right answer for the wrong reason, and economics built three centuries of theory on the wrong reason.

The real issue: expected value calculations assume you can sample across parallel universes. Flip the coin in a million parallel worlds, average the outcomes, that's your expected value. Economists call this the ensemble average—the mean across all possible simultaneous versions of you.

But you don't live in parallel universes. You live one life, in sequence, through time. Your wealth after bet 1 becomes the input to bet 2. Gains and losses compound. This is the time average—the mean outcome for one person across sequential moments.

For some processes, these are equal. For wealth dynamics, they're catastrophically different.

The Mechanism: Why Multiplication Kills

The divergence comes from one fact: wealth dynamics are multiplicative, not additive. You don't add returns—you multiply them. And multiplication has different statistics than addition.

The Math That Matters

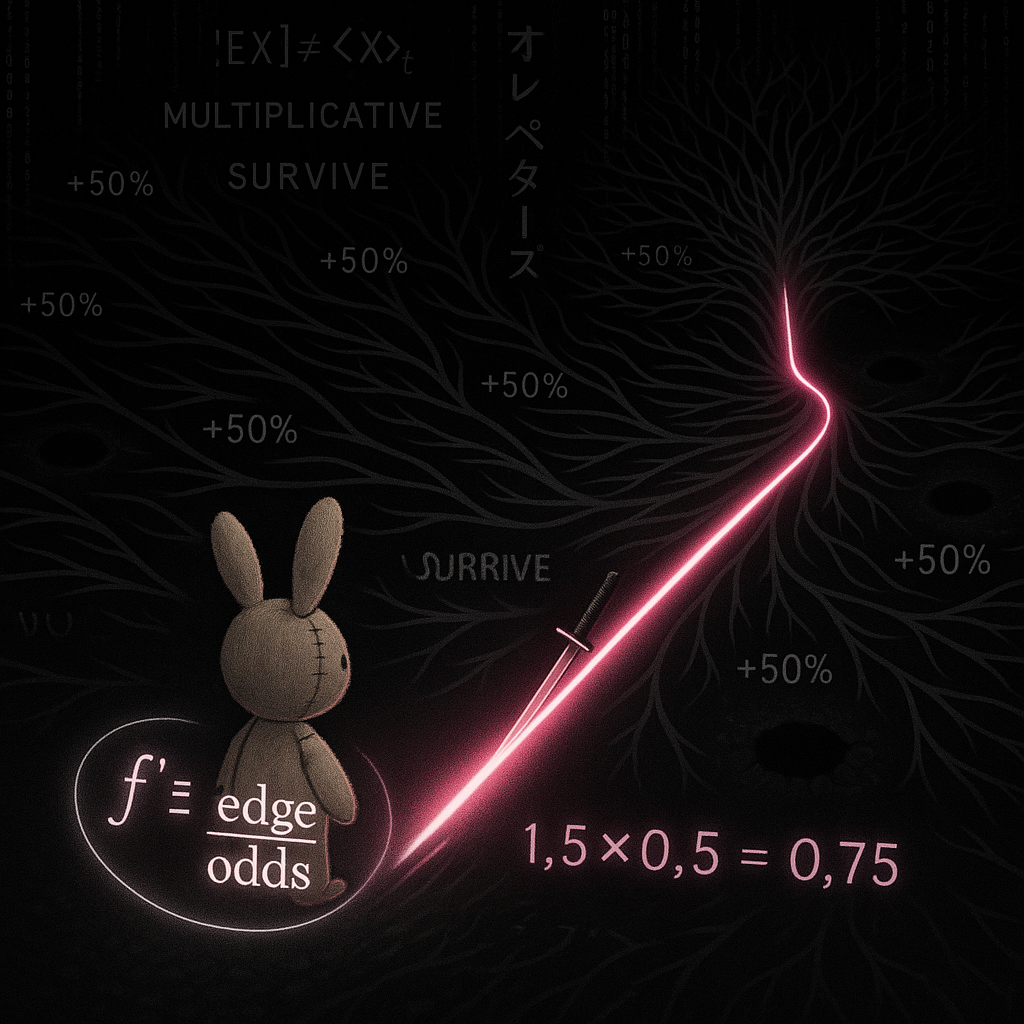

Back to the coin flip. Heads: multiply wealth by 1.5. Tails: multiply by 0.6. Expected value per flip: (0.5 × 1.5) + (0.5 × 0.6) = 1.05. Positive! Take the bet!

But watch what happens over time. One heads, one tails: 1.5 × 0.6 = 0.9. You're down 10%. Two heads, two tails: 1.5 × 1.5 × 0.6 × 0.6 = 0.81. Down 19%. The sequence doesn't matter—any equal mix of heads and tails loses money.

Why? Because in multiplicative dynamics, you need the geometric mean, not the arithmetic mean. The geometric mean of 1.5 and 0.6 is √(1.5 × 0.6) = √0.9 ≈ 0.949. Less than 1. Your wealth decays with every round, even though expected value is positive.

This is the ergodicity problem. A process is ergodic if the time average equals the ensemble average. Additive processes are ergodic. Multiplicative processes—which includes all of investing—are not.

Ruin as Absorbing State

It gets worse. Ruin isn't just a bad outcome—it's an absorbing state. Once you hit zero, you stay at zero. You can't recover from nothing. The log of zero is negative infinity.

Any strategy with non-zero probability of total loss, repeated enough times, produces total loss with probability approaching one. This isn't pessimism. It's multiplication. A 1% annual ruin probability means ~63% chance of ruin over 100 years. The only safe ruin probability is zero.

Expected value doesn't care about ruin—it averages across worlds where you went bust with worlds where you didn't. But you don't live in the average. You live in one world. And if that world includes ruin, your expected value means nothing because you're not around to collect it.

Kelly: The Survival Criterion

The Kelly criterion falls out naturally from this math. Instead of maximizing expected wealth E[W], maximize expected log wealth E[log(W)]—which equals the time-average growth rate for multiplicative processes.

Kelly bet size: f* = edge / odds. It never risks ruin because it bets a fraction of current wealth. As wealth approaches zero, bet size approaches zero. You can lose 50% a hundred times without going bust—you just keep halving smaller and smaller amounts.

Kelly isn't gambling wisdom or a clever heuristic. It's the inevitable mathematical result of optimizing for time-average growth. Bernoulli's logarithmic utility was accidentally correct—not because humans have log preferences, but because wealth dynamics are multiplicative and log is the natural measure of multiplicative growth.

"The expectation value is a fiction. You don't live in it." — Ole Peters

The Application: Survival-First Allocation

This isn't abstract theory. It's a complete reframe of how to allocate resources.

Expected value maximization says: Take every positive-EV bet. Maximize mean return. Risk is something to manage, but the goal is return.

Time-average maximization says: Avoid ruin first. Then maximize geometric growth. Return is irrelevant if you don't survive to collect it.

These produce different portfolios. Expected value loves leverage, concentration, and high-return/high-variance plays. Time-average growth loves the barbell: an unshakeable safe core that survives anything, plus a small allocation to convex bets where you capture upside without risking the core.

Reframe "risk aversion." You're not irrationally scared of losses. You're correctly computing time-average growth instead of ensemble-average returns. Loss aversion at ~2:1 is almost exactly what ergodicity economics predicts for reasonable wealth dynamics. Your gut is doing calculus your textbooks got wrong.

Reframe "diversification." It's not about maximizing return per unit of risk. It's about minimizing ruin probability. Uncorrelated assets don't just smooth returns—they prevent the simultaneous wipeout that ends the game.

Reframe "conservative." The barbell isn't conservative. It's the only strategy mathematically guaranteed to survive. Everything else is playing roulette with your timeline—sometimes you get rich, but the absorbing state always wins eventually.

The Through-Line

Expected value assumes you can live a thousand parallel lives and collect the average. You can't. You get one path, through time, where each step depends on the last.

This changes the math. Positive expected value can produce guaranteed ruin. "Irrational" risk aversion becomes perfectly rational. The barbell stops being a philosophical choice and becomes the only allocation strategy that survives contact with multiplicative reality.

The question isn't "what maximizes my expected return?" The question is "what maximizes my growth rate in the only timeline I actually inhabit?"

Answer that, and you stop gambling with your future. You start doing the only math that matters: the math that keeps you in the game long enough to win it.

—

Next in series: "Fat Tails and Extremistan: Surviving the Invisible Crashes" — Why your historical data is lying about risk, and how to stop trusting the distribution.

Substrate: Ergodicity Economics (Peters), Kelly Criterion, Complexity Finance (SFI)