Nobody Noticed Your Stain

We overestimate others' attention by 2x or more. Learn why the spotlight effect keeps you self-conscious and how small behavioral tests can free you from phantom judgment.

Why you’re convinced everyone saw you trip—and why they definitely didn’t

You spill coffee on your shirt before a meeting. The stain is there, right on the front, visible to anyone who looks.

You walk into the room and feel every eye on you. Or rather, on it. The stain. They must see it. They must be judging you. You spend the entire meeting distracted, convinced everyone is noticing, evaluating, remembering.

After the meeting, you ask a colleague: “Did you notice my shirt?”

“What about it?”

They didn’t see it. They weren’t looking. They were thinking about their own presentation, their own problems, their own stains.

You spent an hour in a spotlight that didn’t exist.

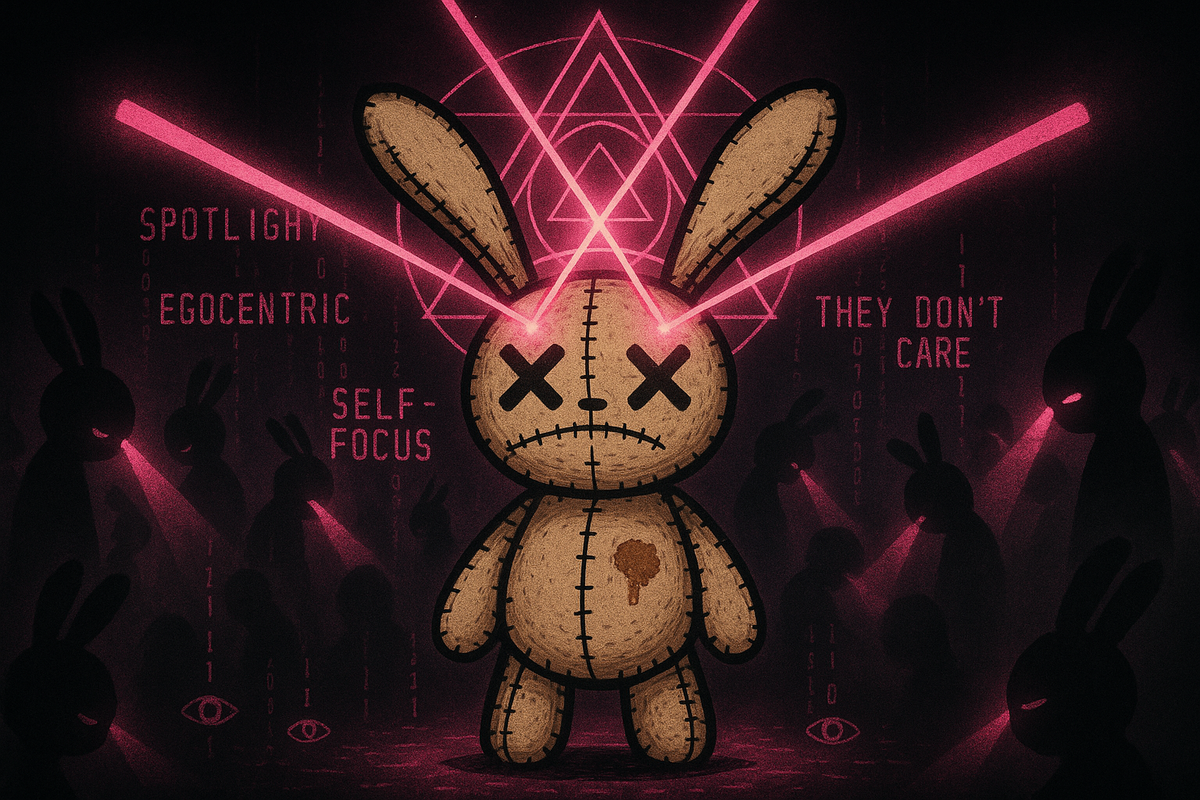

The Spotlight Effect

The spotlight effect is the tendency to overestimate how much other people notice, pay attention to, and remember about you.

You are the center of your own universe. Every moment, you experience yourself from the inside. Your appearance, your mistakes, your awkwardness—these are maximally salient to you. It feels impossible that others aren’t equally focused on them.

But they’re not. They’re focused on themselves. They have their own spotlights, pointed inward, illuminating their own concerns.

The spotlight effect isn’t just a minor miscalibration. In experiments, people overestimate by a factor of two or more. You think half the room noticed your stain; in reality, it’s closer to a quarter, or less.

Why It Happens

Your model of other people’s attention is built from one source: your own experience.

When you think about what others notice, you simulate their perspective using your mind. But your mind is saturated with awareness of yourself. Your embarrassments, your flaws, your stumbles—these are front-of-mind for you, so you project them as front-of-mind for everyone else.

This is called egocentric anchoring. You anchor on your own perspective and adjust to estimate others’. But like all anchoring, the adjustment is insufficient.

You know your stain is huge because you feel it constantly. You assume others see what you feel. But they don’t have access to your internal experience. They just see a person in a meeting—one of many, briefly, while mostly thinking about themselves.

The Evolutionary Logic

In small ancestral groups, social attention mattered intensely. Your reputation was survival. If the group turned against you, you could lose access to resources, protection, mates, everything.

In that context, an inflated estimate of how much others were watching might have been adaptive. Better to be too careful about your social image than not careful enough. The cost of being watched and not realizing it (reputation damage) was higher than the cost of thinking you were watched when you weren’t (unnecessary anxiety).

Your spotlight sensitivity is a leftover from environments where everyone actually did know everyone else’s business, where missteps actually were noticed and remembered, where social attention was tight enough that your errors were genuinely salient to others.

Now you live among strangers. Most people you encounter will never think about you again. The social monitoring that made sense in tribes of 150 is massively overtuned for cities of millions.

The Liberation

Here’s the flip side: nobody cares.

That sounds bleak, but it’s actually freeing. Your mistakes, your awkward moments, your bad hair days, your stumbles in conversation—they’re not being catalogued and judged. They’re not being remembered. They’re barely being noticed.

Other people are too busy worrying about themselves.

This means you can take more risks. Speak up in meetings. Ask the awkward question. Approach the stranger. Try the new thing in public. The downside you fear—social judgment, lasting embarrassment, people thinking less of you—is smaller than your brain insists.

The spotlight isn’t as bright as it feels. And even when people do notice, they forget almost immediately. Everyone’s main character is themselves.

Where It Constrains You

Public speaking. The fear of judgment is often worse than the judgment itself. Audiences are mostly rooting for you, or not paying close attention. The hostility and scrutiny you feel is self-generated.

Social anxiety. The conviction that everyone is watching, evaluating, waiting for you to fail. But they’re not. They’re thinking about their own performance, their own anxieties, their own spotlights.

Style and appearance. Hours spent worrying about outfits, hair, accessories—as if others were conducting detailed assessments. Most people won’t notice, and those who do won’t remember.

Asking for help. The reluctance to ask questions because “everyone will think I’m stupid.” Nobody is tracking your question-to-statement ratio. Nobody’s keeping score.

Recovery from failure. Believing that a mistake has permanently damaged your reputation, when in reality most observers have already forgotten and moved on.

The Companion Effect: Illusion of Transparency

There’s a related phenomenon. The illusion of transparency is the belief that your internal states—your emotions, your nervousness, your thoughts—are more visible to others than they actually are.

You feel your heart racing before a presentation. Surely everyone can see how nervous you are. Your voice must be shaking. Your hands must be trembling. They know.

They don’t know. Internal states are mostly invisible. Your nervous system is screaming, but your exterior is much calmer than you think. Others see a person giving a presentation. They don’t see the internal storm.

This illusion amplifies the spotlight effect. Not only do you think others are watching—you think they can see inside you. The exposure feels total. It isn’t.

The Move

The correction is both cognitive and behavioral.

Cognitively: When you feel the spotlight, remind yourself it’s an illusion. You are overestimating attention by a factor of two or more. Most people didn’t notice. Those who did won’t remember. Everyone is starring in their own movie.

Behaviorally: Test it. Do the thing you’re afraid to do—ask the question, wear the outfit, make the joke—and notice what happens. The reaction is almost always less than you feared. Each test provides evidence against the spotlight.

Reframe the worst case. Even if they notice, so what? Will it matter in a week? A year? The worst case in most social situations is momentary awkwardness, quickly forgotten by everyone including you.

Remember everyone else’s spotlight. The person you’re worried about impressing is worried about impressing someone else. The person you think is judging you is thinking about their own stain. It’s spotlights all the way down.

You’re not the center of anyone’s universe but your own.

That’s not sad. It’s freedom.

Nobody noticed your stain. And even if they did—they’ve already forgotten.

This is Part 9 of Your Brain’s Cheat Codes, a series on the mental shortcuts that mostly work—and the specific situations where they’ll ruin you.

Previous: Part 8: Pretty People Seem Smarter

Next: Part 10: They’re Lazy vs. Traffic Was Bad — The Fundamental Attribution Error