The Metamour Relationship: Your Partners Partner

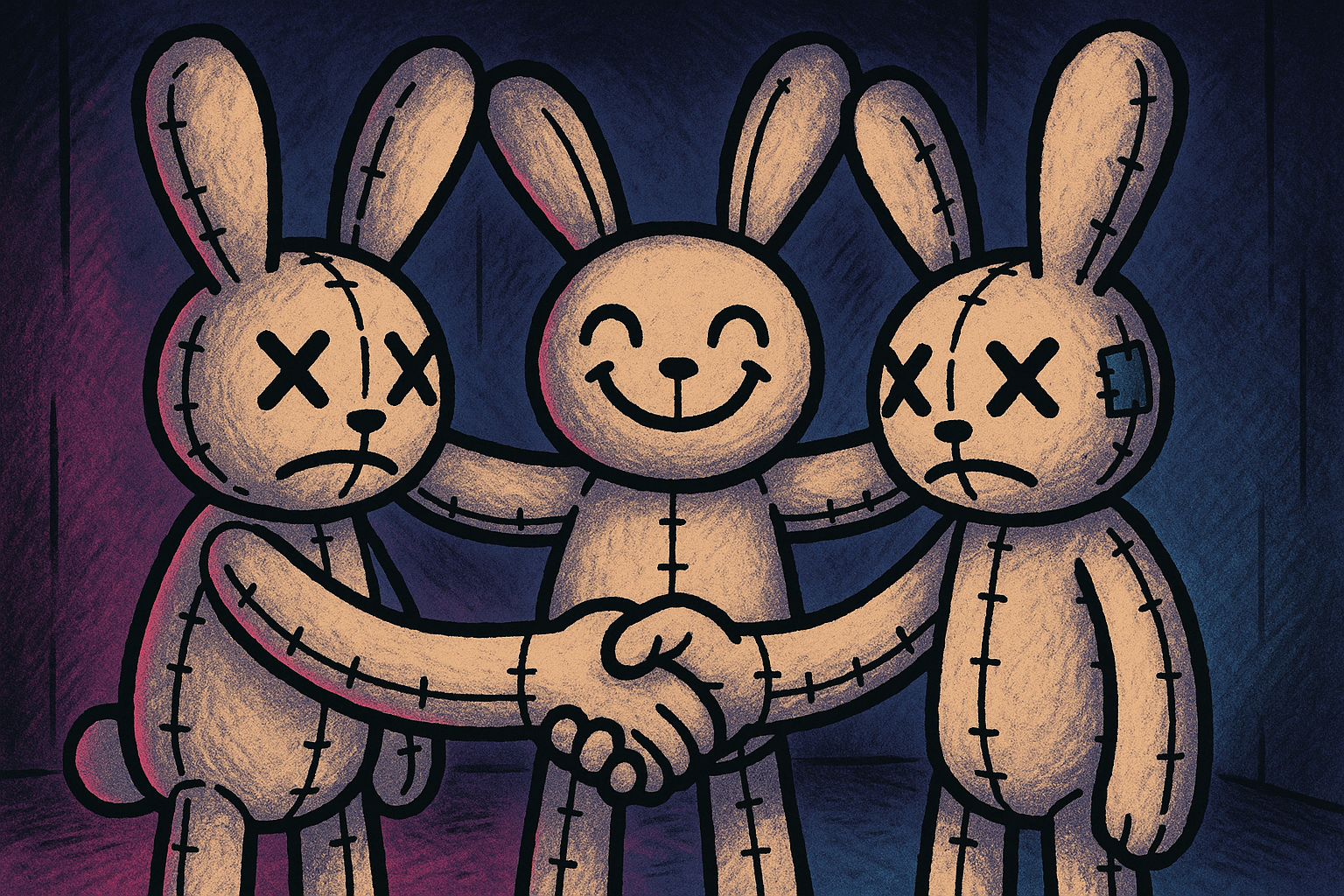

Your metamour is your accidental in-law. No wedding invited them into your life. Your partner's affections did—and now you're connected to someone you didn't choose, might never have met, and have to navigate without any cultural script.

In monogamy, this person would be a rival. Someone to eliminate. In polyamory, they're... what exactly? Family? Acquaintance? Friend? Competitor?

How you answer shapes whether poly feels like abundance or chaos.

The Forced Intimacy Problem

You and your metamour are intimate whether you want to be or not.

You know things about each other. You affect each other's lives. Your partner's time with them is time not with you. Their needs compete with yours for the same finite resource: a person you both love. When they're sick, your partner cancels plans with you to care for them. When they have a crisis, your partner's emotional bandwidth gets consumed. When they're happy, your partner glows in ways that have nothing to do with you.

You didn't choose this intimacy. You didn't choose this person. And yet here you are, entangled. Sharing someone. Affecting each other. Potentially for years.

In monogamy, this person would be eliminated. You'd demand they disappear. In polyamory, they're a permanent fixture in your emotional landscape—someone you have to make peace with, avoid, or actively befriend, but can't simply erase.

There's no template for this. In-laws at least have wedding traditions and cultural scripts. Metamours have nothing. You're improvising a relationship with someone who could be a stranger, a friend, or a rival depending on how this goes. The stakes are high and the instructions are nonexistent.

The Spectrum

Best friends. Some metamours become genuinely close, independent of the shared partner. They text about things unrelated to their mutual love. They hang out without the hinge present. They prefer each other's company. The shared partner is how they met, not the limit of their connection.

This is rarer than kitchen table poly advocates suggest, but it does happen. Usually when the metamours have genuine compatibility—similar interests, values, sense of humor. The relationship to the shared partner brought them together, but the actual friendship sustains itself.

Friendly acquaintances. Warmth without depth. You like them. You're glad they exist. You don't need more than that. You can share a meal, make pleasant conversation, and genuinely mean it when you say "good to see you." But you're not texting them when something funny happens. The relationship exists in the context of the shared partner and doesn't extend much beyond that.

This is probably the most common functional metamour relationship. Enough goodwill to make group events pleasant. Not so much intensity that anyone feels obligated to maintain connection they don't naturally have.

Cordial strangers. Polite, minimal contact. You know they exist. You might exchange pleasantries at events. You're civil when paths cross. Fine for parallel poly where you're not expected to build relationship anyway.

The cordiality is genuine but the interest isn't there. They're your partner's partner. That's the extent of the connection. Nobody's pretending otherwise.

Tense coexistence. You don't get along. Personality clash, value differences, or just bad chemistry. You manage it for the shared partner's sake, but it's work. Every interaction requires emotional labor. You're polite because blowing up would hurt someone you love, not because you feel warmth.

This is sustainable if the structure allows distance. In parallel poly, tense coexistence barely matters—you don't see them. In kitchen table poly, it's a constant low-grade stressor.

Active conflict. Hostile. You actively dislike each other. Being in the same room creates tension. The shared partner is caught in the middle, constantly managing the conflict, unable to have both of you in the same space. This usually destroys something—either one of the relationships ends, or the stress fractures the whole polycule.

Most metamour relationships land in the middle. The goal isn't forcing any particular level—it's finding the level that actually works and not demanding more intimacy than exists naturally.

The Baseline Requirement

You need goodwill.

Not friendship. Not closeness. Just genuine hope that your metamour's life and relationship go well. If you're actively wishing them harm—hoping they break up, hoping your partner stops loving them, hoping they move away—you're in an untenable position. That level of hostility poisons everything it touches.

The person you both love isn't a prize to compete for. They're a person making their own choices. Treating them as the object of competition makes everyone miserable—including, eventually, them. Your partner isn't choosing between you. They're choosing both of you. Or they're not, and the relationship will end for other reasons. But framing metamours as competition creates the very instability you fear.

Goodwill means: when your metamour has good news, you don't secretly hope it falls through. When they're struggling, you don't feel satisfied. When your partner talks about them with affection, you don't feel personally attacked. You can hold space for your partner to love someone else without feeling like it diminishes you.

This is harder than it sounds. The zero-sum thinking of monogamy—if they win, you lose—is deeply installed. Shifting to abundance thinking—their relationship thriving doesn't threaten yours—takes conscious work.

The Attachment Filter

Anxious attachment often struggles with metamours. The very existence of the metamour feels threatening. Every interaction gets analyzed: Did they laugh longer at their joke? Does my partner prefer them? Are they better than me? Is my partner going to leave me for them?

The anxious person watches their partner's face when the metamour texts. They notice when their partner seems excited about plans with the metamour. They compare themselves constantly—body, personality, sexual performance, everything. The metamour becomes the evidence that they're not enough.

The metamour becomes a screen for projection of abandonment fears. The problem is rarely the actual metamour. The problem is what they represent to the anxious nervous system: proof that love is conditional, proof that they could be replaced, proof that "not enough" was always true.

Even when the metamour is lovely, even when they're actively trying to build goodwill, the anxious person can't fully relax. The threat isn't what the metamour does. The threat is that they exist at all.

Avoidant attachment might dismiss metamour relationships as unimportant—which reads as cold. "I don't need to meet your other partners" sounds like healthy boundaries but can actually be dismissal of people who matter to someone you supposedly love. Or they prefer parallel poly specifically to avoid metamour entanglement. The work of relationship-building feels like too much intimacy. More people to show up for. More emotional labor. Better to just not engage.

Avoidants sometimes use parallel poly as an excuse to not do the work of being in community. They want the benefits of polyamory without the actual relating to multiple people it requires.

Secure attachment can approach metamours with genuine curiosity. They're not threatened by existence. They can appreciate what the metamour brings to their partner's life—maybe the metamour shares interests they don't, provides support they can't, offers perspectives they lack. This isn't threatening. It's complementary.

They can build whatever level of connection makes sense without anxiety driving the relationship. If friendship develops, great. If not, cordial acquaintance is fine. The relationship with the metamour gets to be what it actually is, not what anxiety or avoidance demands.

Disorganized attachment may cycle between wanting closeness with metamours (polycule as found family) and perceiving them as threats (intimacy as danger). One week they're texting the metamour about getting drinks. The next week they're convinced the metamour is trying to steal their partner.

The relationship destabilizes as the attachment pattern fluctuates. The metamour has no idea what they did wrong. The answer is usually: nothing. The disorganized nervous system just cycled from "come here" to "go away" and the metamour got caught in the wave.

Compersion Isn't Mandatory

Compersion is feeling joy in your partner's other relationships. Watching them be happy with your metamour and feeling glad rather than jealous. Seeing your partner light up talking about a great date with someone else and feeling warm about their happiness.

It's real. Some people genuinely experience this. They see their partner thriving in another relationship and feel genuine happiness about it. Not gritted-teeth tolerance. Actual joy.

It's not mandatory.

The poly community sometimes treats compersion as the goal—the sign you've "evolved" past jealousy, the mark of enlightened non-monogamy. This is bullshit. Compersion is a feeling some people have sometimes. It's not a requirement for ethical polyamory.

You don't have to feel joy about your partner's other relationships. Tolerating them, respecting them, not sabotaging them—that's enough. You can feel neutral. You can even feel jealous while still honoring the agreements you made. Feelings and actions are different.

Compersion, when it happens, is a bonus. Enjoy it. But don't beat yourself up for not feeling it.

And compersion can coexist with jealousy. You can feel both about the same situation. You can be glad your partner is happy AND feel a pang of jealousy. You can experience warm feelings toward your metamour AND feel threatened by them. Humans are complicated. Emotions don't come in neat packages.

Don't let anyone tell you that you're doing poly wrong because you feel jealous sometimes. Jealousy is a feeling. What matters is what you do with it. Process it. Talk about it. Don't weaponize it. That's the work.

The Failure Modes

Metamour as enemy. If you're treating them as a rival to be defeated, you've missed the point. They're not trying to take your partner. They're trying to have their own relationship. The zero-sum thinking—if they win, you lose—creates the very competition that destroys polycules.

When you're actively trying to make the metamour look bad, sabotaging their relationship, hoping for their failure—you're not protecting yourself. You're guaranteeing misery for everyone, including your partner who's watching you try to destroy someone they love.

Forced friendship. Kitchen table poly expectations can pressure metamours into performing closeness they don't feel. "Why won't you just be friends with them?" becomes a judgment. Authentic distance beats fake intimacy. If you genuinely don't click with your metamour, pretending otherwise helps no one.

The forced friendship becomes a performance everyone can see through. It creates resentment—you resent being pressured, they resent the obvious fakeness, your partner resents having to manage the tension everyone's pretending doesn't exist.

Triangulation. Using the shared partner to communicate things you should say directly—or using them against the metamour. "Tell them I can't make it" instead of texting yourself. "Did they say anything about me?" instead of asking directly. This makes the hinge's life hell.

They become a messenger service instead of a partner. Every communication has to route through them. They're responsible for managing a relationship between two other adults who won't talk to each other. It's exhausting and it's unfair.

Comparison spiral. Constantly measuring yourself against your metamour. They're thinner. They're funnier. They're better in bed. Your partner smiles more when talking about them. The comparison never stops and you always come up short.

There's no winning because the comparison itself is the problem. Even if you "win" some comparison, you'll find another metric where you're losing. The problem isn't that you're objectively worse. The problem is that you're making everything a competition.

Veto as control. Using veto power not to protect yourself but to eliminate a metamour you don't like. This is weaponizing structure. Veto exists for when a relationship is genuinely damaging you. Using it because you're jealous, or because you don't like the metamour's personality, or because you want your partner's full attention—that's abuse of power.

The veto becomes a weapon to control your partner's relationships instead of a safety valve for genuine harm. Once used this way, trust evaporates. Your partner knows you'll eliminate anyone who makes you uncomfortable, which means they can never fully invest in anyone else.

The Honest Navigation

The metamour relationship is genuinely hard. You're connected to someone you didn't choose, through someone you love, without social scripts. No one teaches you how to do this. There's no Miss Manners guide to metamour etiquette. You're building the plane while flying it.

What works: goodwill, appropriate boundaries, communication proportional to the level of connection, and enough security to not project all your fears onto this convenient target.

Goodwill means genuinely hoping they thrive. Appropriate boundaries means neither forcing friendship nor treating them as invisible. Communication proportional to connection means: if you're kitchen table, talk directly; if you're parallel, you barely need to communicate at all. Don't force intimacy that doesn't exist. Don't avoid necessary communication out of discomfort.

Security means recognizing that your partner loving them doesn't diminish their love for you. That their relationship can be beautiful without threatening yours. That there's not a finite supply of love to compete over. This security might not come naturally. You might have to build it through therapy, through processing, through repeated exposure to your partner being happy with someone else and coming home to you anyway.

What fails: treating metamours as threats, forcing closeness that isn't organic, using them as scapegoats for problems that are actually between you and your partner.

If your partner isn't giving you enough time, that's between you and them. The metamour isn't stealing time—your partner is choosing how to allocate it. If your partner seems distant, that's a relationship problem, not a metamour problem. Using the metamour as the explanation lets you avoid the harder conversation about what's actually wrong in your relationship.

The metamour who looks like a threat might just be a person also trying to figure this out. They didn't choose to be in your life either. They're navigating the same awkward terrain, probably also worried about whether you hate them, probably also unsure what the right level of contact is.

Your attachment style shapes how you see them before you even meet. Anxious attachment sees threats. Avoidant attachment sees obligations. Secure attachment sees people. Know your pattern. It's filtering your perception of someone who might actually be perfectly reasonable if you could see them clearly.