The Kids Are Alright: Stop Optimizing for the Remembered World

We've spent this series dismantling the standard story.

The standard story says kids are broken—distracted, lazy, anxious, addicted, unprepared. It says parents need to fix them through better discipline, less screen time, more structure, clearer rules.

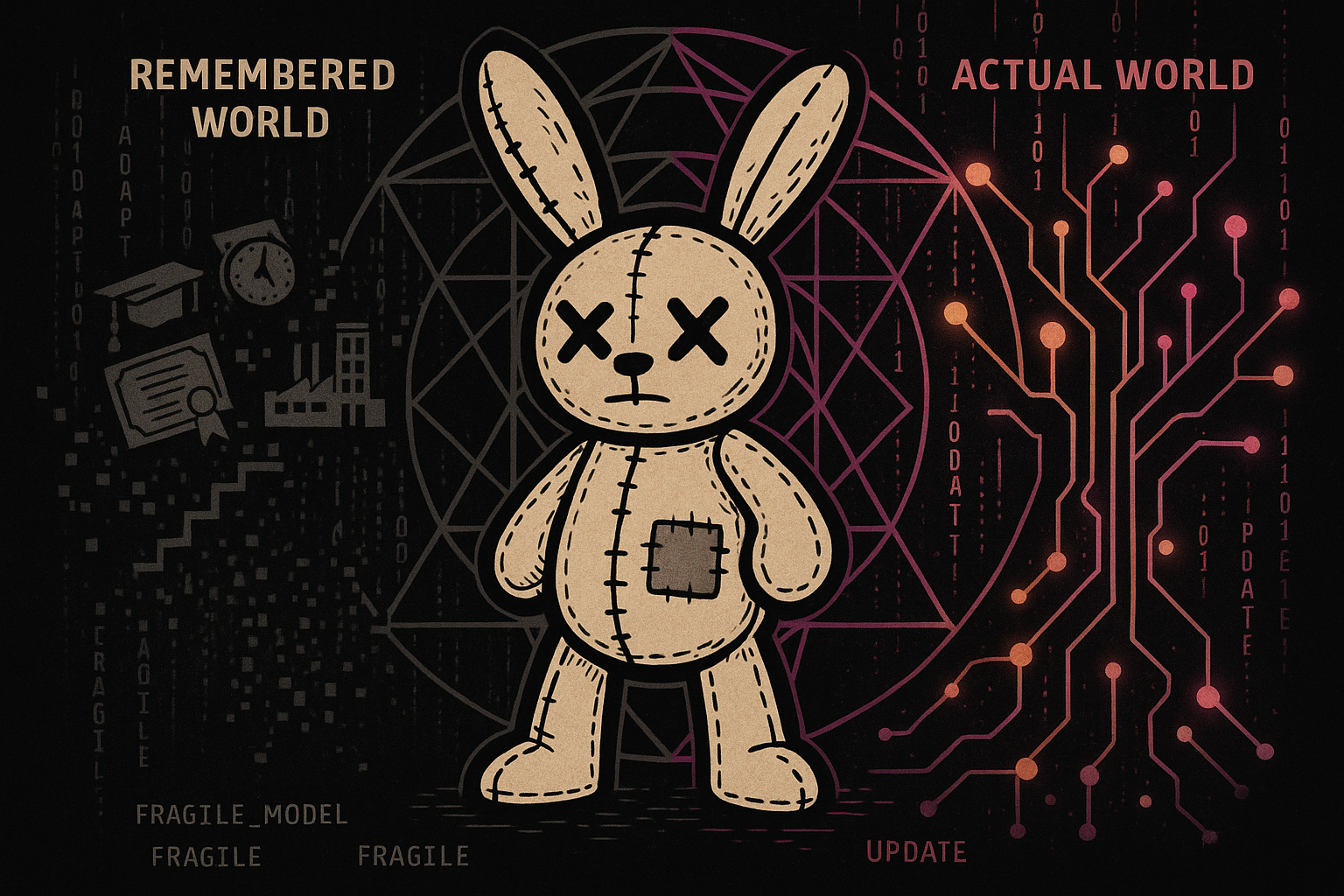

The alternative story says: your model of childhood is fragile, not your children.

Let's put it all together.

The Core Insight

Every generation grows up in a world their parents didn't. Every generation develops traits that look pathological to the previous generation. Every generation turns out roughly fine.

What changes is the environment. What stays constant is parents measuring kids against a remembered world that no longer exists.

The parenting frameworks (Baumrind's styles) assumed predictable futures. The disorder categories (DSM criteria) assumed stable environments. The success metrics (grades, college, career) assumed legible pathways.

None of these assumptions hold anymore.

This doesn't mean the kids are fine and there's nothing to worry about. It means the frame is wrong. The kids aren't failing to meet reasonable standards. The standards are calibrated to conditions that have evaporated.

What We've Covered

Parenting styles were designed for a different world. The authoritative ideal—high warmth, high structure—works when parents know what they're preparing kids for. When the future is uncertain, structure becomes guesswork dressed as confidence.

Authoritative parenting is two things bundled together. The relational component (warmth, responsiveness, co-regulation) transfers regardless of context. The structural component (rules, expectations, guidance toward outcomes) is only as good as the parent's model—which might be wrong.

Attention isn't broken; it's calibrated differently. The ADHD explosion reflects a mismatch between attention patterns shaped by information-rich environments and institutional demands shaped by information-scarce environments. Same brains, different fit.

Screen time is a useless category. Lumping together creation and consumption, connection and isolation, active and passive use obscures more than it reveals. The terrain matters; the duration doesn't.

Friction intolerance is rational. Every generation optimizes for cognitive load. Kids raised in a friction-minimized economy have low friction tolerance—not because they're lazy, but because they're calibrated to the world we built.

Present-orientation might be smart. Ergodic reasoning—understanding that you're not the average, you're one path through a possibility space—leads to different financial logic than naive compounding models. The avocado toast math might be better math.

Disorder is contextual. When the environment shifts faster than the diagnostic criteria, traits that were neutral become pathological and pathological traits become neutral. The problem might be the fit, not the kid.

Skills are being acquired; you just can't see them. Content creation, algorithm navigation, community management, attention arbitrage—these don't appear on résumés yet but will matter in an economy that doesn't fully exist yet.

Co-regulation is the skill that transfers. When content-specific guidance fails, nervous-system presence remains. You can't prepare them for a specific future; you can stay connected while navigating uncertainty together.

The Practical Synthesis

So what does this mean for how you actually parent?

1. Update your model of success.

The pathway you followed—school → credentials → stable career → home ownership → retirement—might not exist for them. Stop measuring them against it.

Ask instead: Are they developing adaptability? Learning agility? Network? Emotional regulation? These matter regardless of what the economy looks like in 2045.

2. Distinguish content from capacity.

Content is specific knowledge, skills, rules—things that might become obsolete.

Capacity is the ability to learn, adapt, connect, regulate—things that remain valuable regardless of conditions.

Pour energy into capacity. Hold content loosely.

3. Let go of friction nostalgia.

They shouldn't have to pay costs that don't develop anything. Driving to Blockbuster didn't build character; it was just the price of watching a movie.

Identify which friction is developmental (learning an instrument, building relationships, physical training) and which is pure cost. Insist on the former. Let go of the latter.

4. Reframe the "time-wasting."

What looks like wasted time might be skill acquisition you can't recognize because the skills don't have names yet.

Watch what they're actually doing. Ask questions instead of assuming. They might be building things you can't see.

5. Prioritize regulation over content.

When you don't know what to say, don't say anything. Just be present and regulated.

Your nervous system being available for them to couple with matters more than your advice. Especially when your advice is based on a world that's receding.

6. Accept that you don't know.

The most honest thing you can tell your kid about the future is: "I don't know."

This isn't failure. It's accuracy. And modeling comfort with uncertainty is itself a gift.

The Bigger Picture

Every generation has thought the next one was going to hell.

Socrates complained about young people's disrespect. Victorian moralists panicked about novels. 1950s parents worried about rock and roll. 1980s parents worried about video games. 2000s parents worried about the internet.

The kids turned out fine. Not because there were no problems—there were always problems—but because each generation adapts to its actual environment rather than the remembered environment of the previous generation.

Your kids are adapting to their environment. It's an environment with higher information density, more parallel demands, less predictable pathways, and different friction profiles than yours.

Their adaptations look wrong to you because you're measuring against the wrong baseline.

Measured against the world they actually inhabit, most of them are doing remarkably well.

The Final Reframe

The kids aren't alright because they're meeting some external standard. They're alright because they're doing what every generation has always done: adapting to the world they're actually in rather than the world their parents remember.

Your job isn't to fix them.

Your job is to:

- Stay connected while the terrain shifts

- Offer your nervous system as a stable reference

- Support their capacity development without pretending to know where it leads

- Let go of the world you remember and see the world they're actually navigating

The panic is understandable. Parenting is terrifying, and the rate of change makes it more terrifying.

But the kids are doing what they've always done: growing up in a world their parents don't fully understand and figuring it out anyway.

They're alright.

The question is whether you can see it.

This completes the Kids Are Alright series. For more on navigating uncertainty, see our Future Inevitability series.