Captain Flint: The Founder Who Lies for the Mission

Part 2 of 13 in the Black Sails: A Leadership Masterclass series.

Every lie Captain Flint tells is a lie you've told. Or will tell. Or are telling right now.

To the crew: "We're chasing the Urca gold. Five million dollars. Everyone gets rich." To his partners: "We're building a pirate republic. Freedom from the empire." To Eleanor: "I care about Nassau's future." To himself: "This is about principle. This is about justice. This is about civilization's corruption."

All lies. Useful lies. Necessary lies. Lies that build things that truth couldn't build.

The real story? A British naval officer fell in love with a lord's son. The empire destroyed them for it—institutionalized Thomas, cast out James. Captain Flint is revenge wearing a mission statement. The pirate republic is a weapon pointed at the people who took everything from him.

But you can't recruit a crew with "help me process my grief through violence against the state." You need a story they can fight for. So Flint gives them one.

The pitch deck isn't the truth. It's the story that makes the truth achievable.

I've been thinking about this for years now: the lie that works becomes the truth that matters.

Watch what happens. Flint tells the pirate republic story so many times, with such conviction, to so many people, that it starts becoming real. Not just to the crew—to Flint himself. He needs the lie to work, so he invests in it. He invests in it, so he starts caring about it. He cares about it, so it stops being entirely a lie.

Nassau actually becomes a functional republic. People actually fight for it. Something real emerges from the instrumental fiction.

This is how companies get built. The founder tells the vision story—partly true, partly aspiration, partly manipulation—and the telling produces the reality. People join. They build. They create. And suddenly the company is the thing the founder only half-believed when they started pitching.

The lie eats the liar. But sometimes it gives birth to something true in the process.

There's a mechanism here worth understanding. The lie creates commitment. Flint tells the pirate republic story to recruit crew. The crew joins based on that story. Now Flint has crew who expect him to pursue the republic. Their expectations constrain his options. He can't pivot away from the lie without losing them.

So the lie becomes operationally true even if it started instrumentally false. Flint is building a republic because he said he was building a republic and people believed him and now he's trapped by their belief into actually doing it.

This is the founder bind. You tell a story to raise capital, recruit talent, generate momentum. The story works. Now you're locked into delivering on it. The performance becomes the reality. You can't admit it was ever performance without destroying everything the performance built.

Most founders experience this but won't admit it. Flint is the version who knows he's performing and keeps performing anyway because stopping would mean admitting the whole thing was theater—and the people who believed aren't ready for that admission.

Here's where Flint crosses a line that most business content won't acknowledge exists.

The noble lie assumes the liar will honor the spirit of the lie. Will actually pursue the outcome that justifies the telling. Will, at some point, deliver on the promise.

But Flint won't. Not really. Not when it conflicts with the real mission.

He'll sacrifice Nassau for his war. He'll sacrifice the crew for his vendetta. He'll sacrifice everything—because his goal was never their goal. The story he told them was always, at some level, purely instrumental. The people who believed it were always, at some level, expendable.

Silver sees this clearly. "This man will burn everything down for a personal grievance he's been nursing for a decade." Silver isn't wrong. That's exactly what Flint will do.

So when does the noble lie become simple manipulation? When does the visionary become the narcissist? When does the founder become the con artist?

The show doesn't answer. The show just shows you a man walking that line for four seasons and lets you sit with your own judgment.

There's a cost to being Flint that nobody talks about.

Not the external cost—the enemies, the betrayals, the empire coming for him. Everyone talks about that.

The internal cost: he can never stop performing.

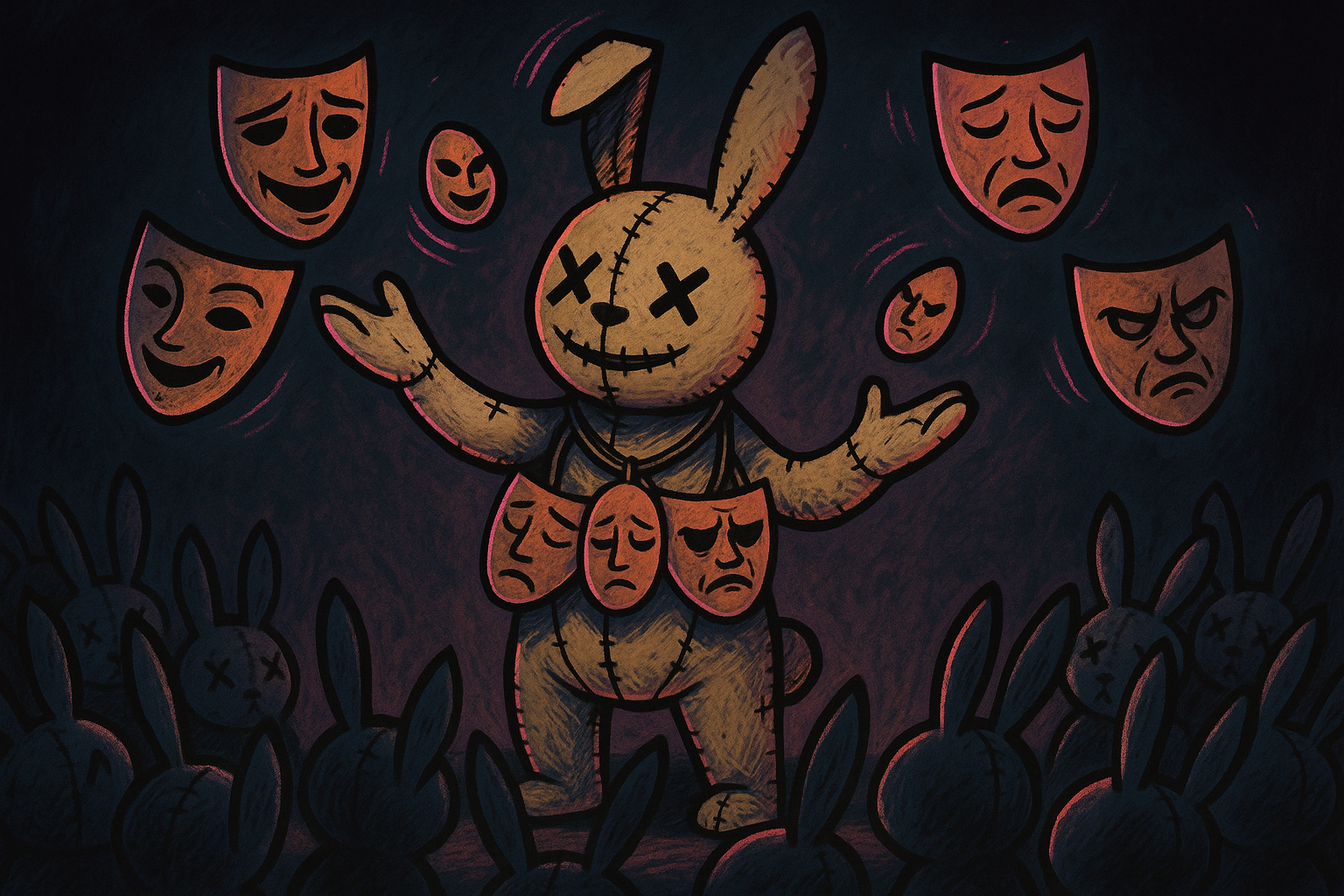

Even in private. Even with allies. Even, eventually, with himself. The mask becomes the face. Captain Flint consumes James McGraw. By the end, he's told the lie so long that he doesn't know where the performance stops and the person starts.

His war is revenge—but also more than revenge. The pirate republic is instrumental—but also something he genuinely cares about now. The men are pawns—but also men he's responsible for. The categories have collapsed.

This is founder psychology at scale. The vision you pitched becomes the vision you believe. The story you told becomes the reality you inhabit. You started performing certainty; now you can't remember what doubt felt like.

James McGraw wanted revenge. Captain Flint wanted a republic. Somewhere along the way they merged into something that wanted both and neither and couldn't tell the difference.

This is the psychological cost of leadership through narrative. You can't tell inspiring lies without being shaped by them. The crew needs to see certainty, so you perform certainty. You perform it long enough, you become it. Not because you're convinced—because the performance becomes your default mode and there's no one you can drop the mask around.

Flint has no peers. No one he can confess to. No one who knew James McGraw well enough to call him out when Captain Flint goes too far. He's alone in his performance, and loneliness makes the performance more complete, which makes him more alone.

This is what happens to founders who can't vulnerability with anyone. They become the pitch. The pitch becomes them. Five years in, they can't remember which parts of the vision they believed and which parts they made up to close the round. Ten years in, it doesn't matter—the made-up parts have as much reality as anything else.

The noble lie is a loan. Eventually it comes due.

It works while circumstances support it. While the story matches enough of reality. While people want to believe.

It fails when reality diverges too far. When the Urca gold doesn't solve the problems it was supposed to solve. When the crew realizes they've been fighting for someone else's vendetta. When the people you've been managing realize they've been managed.

Flint's lies start collapsing in Season 3. The truth seeps through. The coalition fractures. And Flint discovers what every founder eventually discovers: you can't pitch your way out of a product problem.

The lie got him this far. The lie can't carry him further. And now he has to find something else—or watch everything he built fall apart.

Here's what triggers the collapse: Silver sees through it. Not because Silver is smarter—because Silver has no emotional investment in the lie. He joined late, never believed the story, only cared about outcomes. When Silver looks at Flint, he doesn't see a visionary. He sees a traumatized man weaponizing his grief.

And once someone sees it clearly, they can name it. And once it's named, others can see it too. The spell breaks. Not all at once—some keep believing because they need to believe. But enough doubt enters the system that the lie stops being load-bearing.

This is the moment every founder fears: when someone on the team says out loud what everyone was thinking quietly. When the emperor-has-no-clothes moment arrives. When the shared hallucination that made everything work suddenly stops working.

Flint tries to recapture the momentum. Makes the pitches more dramatic. Pursues victories more desperately. But desperate energy repels rather than attracts. The crew can smell the fear. They realize Flint needs them more than they need Flint. The power dynamic inverts.

Should leaders lie?

The naive answer is no. Truth is a virtue. Lying is wrong. Leaders should be honest.

The sophisticated answer is that it's complicated. Leaders manage meaning. Meaning-making sometimes requires simplification, selective emphasis, narrative construction. The line between "inspiring vision" and "noble lie" is blurry by design.

The cynical answer is obviously yes. All leadership is performance. All vision is story. The only question is whether the lies work.

Flint embodies all three answers simultaneously. He lies consciously, strategically, effectively. His lies enable things that truth couldn't. His lies also corrupt things that might have stayed clean. His lies build a republic and poison the builder.

The show never tells you whether he's a hero or a villain. It just shows you a founder lying, and what those lies produce—the good and the bad and the complicated middle—and leaves you to decide.

Here's what I take from Flint:

Some things can only be built with lies. Some people can only be moved by stories. Some visions can only be achieved by leaders willing to simplify, manipulate, perform.

But lies compound. Lies isolate. Lies consume the person telling them. The noble lie is powerful, but it costs something, and the cost grows, and one day you look up and realize you don't know what's true anymore.

Flint built a pirate republic. It was real. It mattered. It existed because he lied it into existence.

Then it fell apart. Partly because of the lies. Partly because of the things lies can't solve. Partly because lies and reality eventually collide, and reality doesn't care how good your story was.

The question every founder has to answer: what are you willing to lie about? Where's the line? How much simplification is inspiration and how much is manipulation? When does the noble lie become just a lie?

Flint never drew that line. Or drew it and kept moving it. By the end, he's so deep in the lie that extraction is impossible. He can't admit what he's done without destroying what he's built. He can't pivot without betraying everyone who believed. He's trapped in his own narrative.

This is the failure mode of founder-as-storyteller. The story becomes a prison. You're performing for an audience that believes you, and you can't disappoint them, and you can't step off stage, and eventually the performance is all there is.

Some founders navigate this. Find ways to be honest enough to stay sane while being inspirational enough to keep building. Flint never found that balance. His honesty died with Thomas. Everything after was performance.

Captain Flint: founder, visionary, liar.

The same man. That's the point.

Previous: Black Sails Is the Best Business Show Ever Made Next: Long John Silver: The Redpill Savant Who Read Greene in the Bunk