Fishbowl Parties and the Swinger Origin Story

Can you share bodies and keep hearts?

The swingers of the 1950s bet yes. They were half right. The emotional firewall they tried to build was leaky from the start. But their experiment proved something: consensual non-monogamy was possible. Later generations would figure out for whom.

The Myth and the Reality

The origin story everyone tells: World War II fighter pilots, facing likely death, made pacts to care for each other's widows. "Care for" became euphemism. Key parties emerged. Suburban swingers were born.

The myth is probably false. Historical evidence for these pacts is thin to nonexistent. But the myth persists because it provides a romantic origin story for something that actually emerged from much messier, more mundane circumstances—boredom, opportunity, and the particular isolation of postwar American suburbs.

The phenomenon it explains—married couples sharing sexual partners while maintaining primary bonds—emerged from real conditions:

Military communities with young couples far from family oversight. The particular bond of shared danger creates intimacy between couples that civilian life doesn't replicate. Young marriages formed quickly—marry before deployment became standard practice. These couples barely knew each other, were stationed far from home, and faced the constant possibility of death. Alcohol flowed freely. Boredom was crushing. Privacy was absolute. The combination was volatile.

Military bases created their own social ecosystems. The same hundred couples, rotating through the same parties, month after month. Everyone knew everyone. Betrayal meant social death, which paradoxically made experimentation safer—you couldn't just ghost someone when you'd see them at the commissary tomorrow. The accountability was built in.

Suburban anonymity where no one knew your parents. The postwar suburb was historically novel: neighborhoods of strangers, couples isolated in nuclear units, no extended family watching. Your neighbors didn't know what church you grew up in. Your spouse's family might be three states away. You could experiment with your marriage and no one who'd known you as a child would ever find out.

This privacy was unprecedented in human history. For most of time, humans lived in villages where everyone knew everyone's business. The mid-century suburb inverted this—you lived surrounded by people who knew nothing about you except what you chose to show. Privacy enabled experimentation. Anonymity created permission.

The sexual revolution's first wave. Kinsey's reports (1948 for men, 1953 for women) revealed Americans' actual behavior diverged wildly from stated norms. Extramarital sex wasn't rare—it was common, just hidden. People were already doing this. Now they knew they weren't alone.

The reports functioned as social proof. If half of married men had affairs, and a quarter of married women, then maybe the monogamy norm was the lie and the cheating was the truth. Swinging offered a way to have what people were already taking—just honestly instead of deceptively.

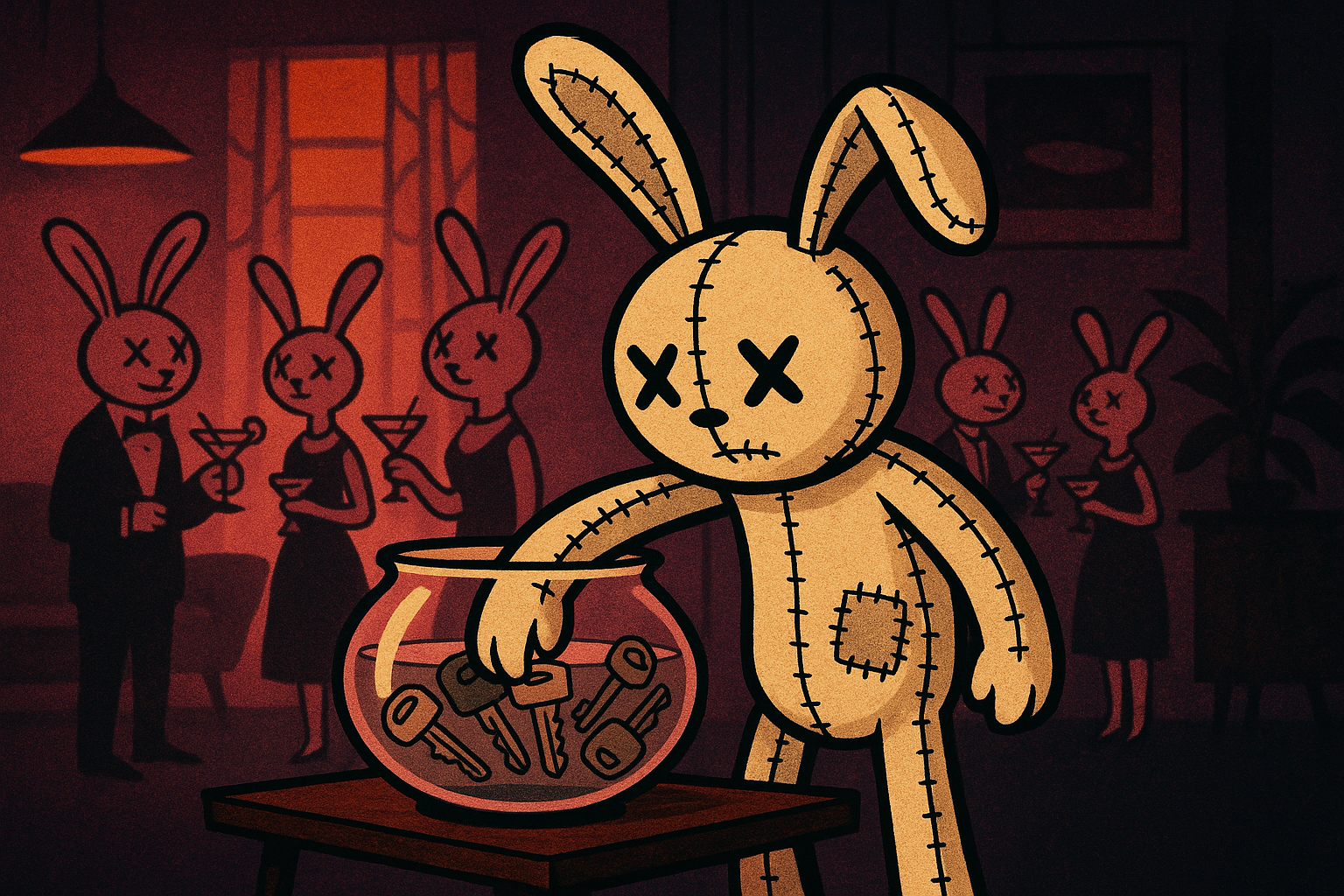

How the Key Party Worked

The classic setup:

- Couples arrive at a party

- Men put car keys in a bowl

- At evening's end, women draw keys

- You go home with whoever's keys you drew

The randomness served multiple functions. Plausible deniability—"it was just chance" removes the sting of active choosing. You didn't select him; fate did. This emotional sleight of hand let people do what they wanted while maintaining the fiction that they didn't really want it.

Democratic distribution—no one gets rejected. In a room where everyone's keys go in the bowl, everyone goes home with someone. No awkward pairing off. No obvious winners and losers. The randomness was the great equalizer.

Reduced negotiation—skip the awkwardness of asking directly. The key party eliminated the entire negotiation phase that makes sexual encounters complicated. No one had to seduce anyone. No one had to ask. The structure did the work.

And it worked even when everyone was drunk. Which they usually were. The alcohol provided additional plausible deniability—"we were drunk, it didn't mean anything"—while also lowering the inhibitions that might have prevented participation in the first place.

But here's what the structure revealed: the couple remained the unit. The rules protecting couple primacy were strict, almost paranoid in their specificity.

No solo play—both partners present or neither participates. If your spouse couldn't make the party, you didn't go. This wasn't just fairness; it was mate-guarding dressed as equality. Both partners had to witness what the other was doing. No opportunities for secret escalation.

No dating—sex at events only, no ongoing relationships. You didn't exchange numbers. You didn't meet for coffee. What happened at the party stayed at the party. The encounters were anonymous even when everyone knew each other's names. The structure prevented intimacy from having room to grow.

No emotional connection—physical only, feelings are cheating. This was the central rule, the load-bearing wall of the entire structure. You could fuck someone else's spouse. You couldn't love them. You couldn't even really like them beyond surface friendliness. Emotional infidelity was the unforgivable sin; physical infidelity was Saturday night.

Sometimes no same-couple repeats—prevents attachment formation. Some swinger groups rotated partners deliberately, ensuring you never played with the same couple twice in a row. Familiarity breeds attachment. Attachment threatens the primary bond. Better to keep everyone strange.

The logic: you can share bodies without sharing hearts. Keep the sex recreational and contained. The marriage is the real relationship; everything else is entertainment. Sex is like tennis—you can play with other people without it meaning anything about your actual partnership.

This logic worked. Sometimes. For some people. When it held.

Where It Broke

The emotional firewall didn't hold.

Oxytocin doesn't check the rules. The neurochemistry of sex bonds regardless of intent. Orgasm releases bonding hormones designed to create attachment. You can decide intellectually that sex is recreational, but your brainstem is running different software. It thinks you're pair-bonding. It responds accordingly.

Some couples discovered that "just sex" became feelings—violating the core premise, threatening the primary relationship with exactly what the structure was designed to prevent. The wife who was supposed to treat the other man as a living dildo found herself thinking about him during the week. The husband who was just having fun started to actually care whether his swing partner was happy. The feelings emerged despite everyone's best intentions and all the rules designed to prevent exactly this.

Consent was murkier than anyone admitted. The lifestyle's official position was that everyone participated enthusiastically. The reality was messier. Some partners agreed to swinging under pressure—wanting to please their spouse, fearing abandonment if they refused, believing they should be cool enough to handle it. The first experience was often genuinely consensual. The fifth time, the tenth time, when the initial curiosity had worn off and what remained was going through motions to keep your partner happy—that's where consent got complicated.

Enthusiastic mutual consent is harder to verify than the lifestyle assumed. "Yes" can mean many things: "Yes, I genuinely want this" and "Yes, I'll do this to keep you" sound identical from outside. Many couples swung for years before one partner finally admitted they'd never actually wanted it. By then, the resentment was profound.

Gender dynamics were uneven. Early swinging was often more beneficial for men—more variety, fewer social consequences—than women, who bore more risk and were sometimes pressured to participate. The sexual double standard didn't disappear just because couples were swinging. A man who swung was adventurous. A woman who swung was a slut—even within the lifestyle itself, subtle hierarchies emerged. Women's participation was simultaneously required (couples only, no single men) and judged.

Women also bore more of the physical risks—pregnancy, STIs with more serious consequences for female anatomy, higher rates of sexual violence. The lifestyle was theoretically egalitarian. In practice, women were more vulnerable.

And there was no framework for when it went wrong. The lifestyle had elaborate rules for playing but few tools for processing jealousy, hurt, or the discovery that this wasn't working. If you started swinging and discovered you hated it, what then? Admitting failure meant confronting the possibility that your marriage needed something you'd tried and failed to provide. Easier to keep swinging and pretend it was fine.

The community also punished exit. If you left the lifestyle, you often lost your entire social circle. The friends you'd made at parties weren't really friends—they were playmates. Stop playing and the invitations stop. The lifestyle became a trap: stay and be miserable, or leave and be alone.

The Attachment Sorting

Swinging self-selected for certain attachment styles and destroyed others:

Avoidant attachment often liked the structure. Sex without emotional demands. Variety without vulnerability. The rules prevented intimacy from developing with swing partners, which suited avoidants perfectly. You could have sex with multiple people while never really being close to anyone—including your spouse.

The danger: using swinging to avoid deepening intimacy with the primary partner. For avoidants, swinging could become a sophisticated escape mechanism. Why work on emotional connection with your wife when you're getting variety elsewhere? Why address the distance in your marriage when the lifestyle frames that distance as healthy boundaries? Swinging gave avoidants permission to never fully show up.

Secure attachment could potentially handle swinging if both partners genuinely wanted it. The key word is "genuinely"—not tolerating it, not agreeing reluctantly, but actively desiring the experience. Secure couples who swung successfully treated it as shared adventure with excellent communication.

These couples were rare but real. They checked in constantly. They had explicit veto power that felt safe to use. They could talk about jealousy when it emerged without the conversation becoming an indictment. They swung because they wanted to, not because they were fixing something broken. For them, swinging added spice to an already satisfying meal.

Anxious attachment typically suffered. Watching your partner with someone else triggers every abandonment fear. Even if the anxious partner initiated—sometimes they did, seeking excitement or trying to seem cool—the reality was usually devastating.

The anxious person would agree to swing for various reasons: to prove they weren't jealous, to keep their partner from leaving, to seem sophisticated and modern. But the actual experience of watching their partner attracted to someone else, aroused by someone else, choosing to be with someone else—it confirmed every terror. You're not enough. They want someone else. They're going to leave.

The structure provided no reassurance. In fact, it was designed to prevent reassurance. The whole point was that your partner was having sex with someone else. That's not reassurance. That's confirmation of your worst fears. Just exposure to worst fears, again and again, with no framework for processing the activation except "you agreed to this, deal with it."

Disorganized attachment was drawn to the intensity but struggled with the rules. The push-pull of wanting connection and fearing it played out destructively. The intimacy of swinging—even though it was supposed to be "just sex"—triggered engulfment fears. The distance maintained by the rules triggered abandonment fears. There was no stable position. Every experience confirmed that relationships are simultaneously necessary and dangerous.

What They Got Right

For all its limitations, early swinging pioneered tools that modern ENM still uses:

Explicit rules. Unlike affairs, everything was negotiated upfront. What's allowed, what's forbidden, what requires discussion. This was radical transparency in an era when most couples never discussed sex explicitly at all. The lifestyle forced couples to articulate boundaries that would have otherwise stayed assumed and unspoken.

The act of rule-setting itself built intimacy. You had to talk about what you wanted, what you feared, what you could handle. These conversations required vulnerability. Many couples found that the negotiation process deepened their relationship even before they attended their first party.

Couple veto power. Either partner could stop at any time. No explanation required. This preserved couple primacy while allowing exploration. If something felt wrong, you could pull the emergency brake. The veto wasn't failure—it was safety.

Community accountability. Reputation mattered. Violate norms and you're out. This created surprisingly strong ethical constraints. You couldn't just ghost someone or lie about your relationship status when you'd see them at the next party. The community was small enough that bad behavior had consequences. This accountability system protected participants better than legal structures would have.

Compartmentalization. Sex happened in designated spaces and times, kept separate from daily life. This created clear containers. Monday through Friday was regular marriage. Saturday night was the lifestyle. The compartmentalization prevented the alternative structure from consuming everything. You could experiment without your entire life becoming the experiment.

What They Learned

The attempt to quarantine sex from emotion was only partially successful. The couples who thrived long-term developed emotional tools the early lifestyle didn't provide—processing jealousy, maintaining connection, distinguishing between discomfort and damage.

Processing jealousy meant not just suppressing it but actually working through it. The couples who lasted learned to talk about what triggered them, what helped, what made it worse. They developed practices: checking in before and after parties, creating aftercare rituals, building in recovery time. The lifestyle's early attitude—"if you're jealous, you're not evolved enough"—gave way to "jealousy happens, here's how we handle it."

Maintaining connection became intentional work. Date nights became sacred. The primary relationship needed active tending or it would wither while attention went to the exciting new people. Successful long-term swingers treated their marriage like a garden that needed constant care, not like a foundation that could be taken for granted.

Distinguishing between discomfort and damage was subtle but critical. Discomfort was the feeling of stretching beyond your comfort zone—manageable, potentially growth-inducing. Damage was actual harm to the relationship. Learning to tell them apart prevented both premature quitting (at mere discomfort) and dangerous persistence (through actual damage).

Modern ENM inherits both the innovations and the lessons. The negotiation practices, the emphasis on couple communication, the community structures—all descend from suburban experiments with keys in a bowl.

But modern practice also learned from swinging's failures: emotions can't be fully compartmentalized, consent requires ongoing attention not just initial agreement, and attachment styles determine who can handle what. The polyamory movement explicitly rejected swinging's "no feelings" rule, building structures that accommodate emotional connection alongside physical. Relationship anarchy rejected the couple-centricity entirely.

The swingers were the beta testers. Modern ENM is the refined product, debugged through decades of trial and error.

The swingers asked whether you could share bodies and keep hearts. The answer: sometimes, for some people, under some conditions. Your attachment style is the biggest predictor of which category you're in. Secure attachment might handle it. Anxious attachment will probably suffer. Avoidant attachment might thrive or might use it to avoid intimacy altogether.

The key parties are mostly gone now, relics of a specific historical moment. But the core question they explored—can sexual exclusivity be separated from committed partnership—remains live. Every couple in an open relationship is still answering the question the swingers asked first. The answers are just more nuanced now.