Fat Tails Aren't Just Unlikely—They're a Different Universe

Six-sigma events should occur once every 1.38 million years but happen in markets every few years. Explore why normal distributions fail, how correlation collapses in crises, and what barbell strategies actually work.

Why your risk models are lying and how to stop believing them

Pillar: MONEY | Type: Pattern Explainer | Read time: 9 min

The Lie Your Models Tell

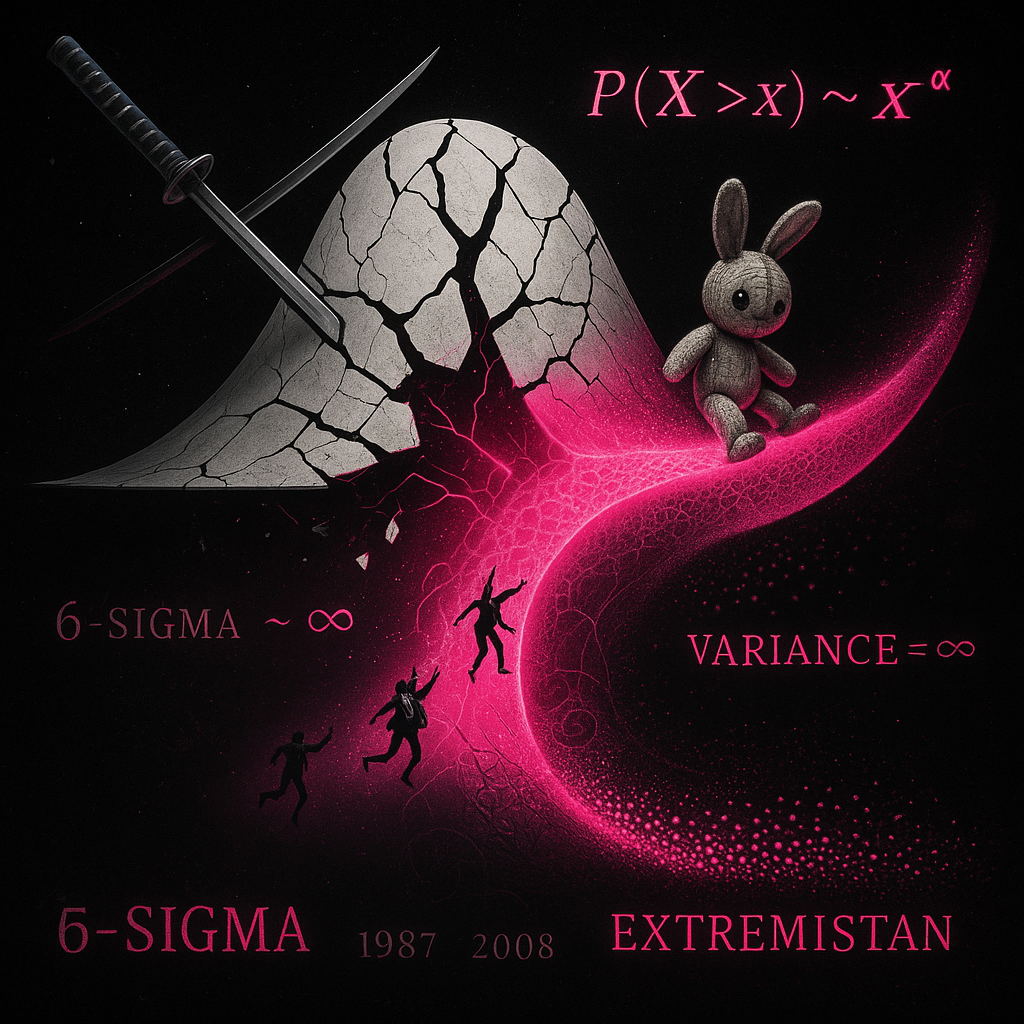

A six-sigma event—six standard deviations from the mean—should occur once every 1.38 million years according to a normal distribution. In financial markets, six-sigma events happen every few years. Black Monday 1987. LTCM 1998. The 2008 crisis. The March 2020 crash.

Either reality keeps producing impossible events, or the model is wrong.

The model is wrong. Financial returns don't follow normal distributions. They follow fat-tailed distributions—where extreme events are orders of magnitude more likely than bell curves predict. This isn't a minor calibration error. It's a completely different statistical universe. And every risk model built on Gaussian assumptions is lying to you about what's actually possible.

The Pattern: Mediocristan vs. Extremistan

Taleb's distinction cuts through the noise. Mediocristan is the land of bounded variables—height, weight, IQ. No single observation can meaningfully change the average. If you sample 1,000 people and add the heaviest person on Earth, the average barely moves.

Extremistan is the land of unbounded variables—wealth, book sales, city populations, market returns. A single observation can dominate all others. Add Jeff Bezos to your sample of 1,000 people and he IS the average. The other 999 become rounding errors.

Markets live in Extremistan. The statistics of Mediocristan—normal distributions, standard deviations, confidence intervals—don't apply. Using them anyway is how quants blow up.

The Mechanism: Power Laws and Infinite Variance

Why Tails Are Fat

Normal distributions have thin tails because they assume independence and bounded influence. Each data point is one roll of the dice, independent of others, with bounded impact.

Markets violate both assumptions. Returns aren't independent—today's crash affects tomorrow's behavior. Influence isn't bounded—a single large player or cascading panic can move the entire market. When independence and boundedness fail, fat tails emerge mathematically.

Many market variables follow power-law distributions: P(X > x) ~ x^(-α). When the exponent α is low enough (≤ 2), variance becomes infinite. Not large. Infinite. Your sample variance doesn't converge no matter how much data you collect. Every historical dataset is an underestimate of true risk.

Agent-Based Generation

Where do fat tails come from mechanistically? Agent-based models show how. Simulate a market with heterogeneous agents—different strategies, different information, different constraints. Let them interact.

Result: fat tails emerge spontaneously. No external shock required. The endogenous dynamics of agents reacting to each other generates extreme events. Herding produces momentum. Momentum produces crowding. Crowding produces fragility. Fragility produces crashes. The tail event isn't an external shock hitting a stable system—it's the system eating itself.

The Correlation Trap

Here's where it gets worse. In normal conditions, assets show low correlations. Your "diversified" portfolio seems protected.

In crisis, correlations spike toward 1.0. Everything falls together. Why? Because the same agents hold multiple assets. The same margin calls force selling across portfolios. The same flight to liquidity hits everything simultaneously. Your diversification was diversified against normal volatility. It was never diversified against tail events.

"In a crisis, all correlations go to one." — Old trading desk wisdom

The Application: Living in Extremistan

Stop trusting backtests. Historical data undersamples tails by definition. The worst event in your backtest is probably not the worst event possible. Your "worst-case" is just the worst case that happened to occur in your sample. The real worst case is worse.

Assume infinite variance. If you're uncertain whether variance is finite or infinite, assume infinite. Design as if the next drawdown could be larger than any you've seen. Because it can be.

Real diversification means different risk factors. Different assets held by the same people aren't diversified—they'll be sold together in crisis. Real diversification means exposures that respond differently to liquidity crises. Usually that means actual cash, not "cash equivalents."

Barbell is the only coherent response. Ultra-safe assets that survive any tail event + convex bets that benefit from tail events. Nothing in the middle. The middle is where you're exposed to tails without benefiting from them.

The Through-Line

Fat tails aren't just "rare events are more common than expected." They're a different statistical universe with different rules. Mediocristan tools in Extremistan get you killed.

The math is clear: returns aren't normal, variance may be infinite, correlations spike in crisis, historical data undersamples tails. Every model that ignores this is a model that will fail precisely when you need it most.

Your risk model should scare you. If it doesn't, it's lying.

Substrate: Power-Law Distributions, Agent-Based Modeling, Correlation Dynamics, Taleb's Incerto