Failure Engineering: Blast Radii and Error Budgets

Why designing for failure is the only way to not fail

The Wrong Question

"How do we prevent this from failing?"

Wrong question. Failure isn't preventable. Every complex system will fail—components degrade, networks partition, humans make errors, edge cases you never imagined will emerge from the combinatorial darkness. The question isn't whether failure happens. The question is what happens when it does.

Google's Site Reliability Engineering, Netflix's Chaos Engineering, Amazon's correction of errors—these aren't paranoid overkill. They're the only rational response to systems too complex to fully understand, too interconnected to fully isolate, and too critical to let fail catastrophically.

Failure is a feature. The only question is whether you've designed for it.

The Pattern: From Prevention to Containment

Traditional engineering tries to prevent failure through quality control, testing, redundancy. This works for complicated systems—bridges, engines, things with known failure modes.

It doesn't work for complex systems. Complex systems have emergent failure modes—combinations of conditions that were individually fine but collectively catastrophic. You can't prevent what you can't predict.

The shift: from failure prevention to failure containment. Accept that failures will occur. Design systems that fail gracefully—where failures are contained, detected quickly, and recovered from automatically. The goal isn't zero failures. It's zero catastrophes.

The Mechanism: The Engineering of Graceful Failure

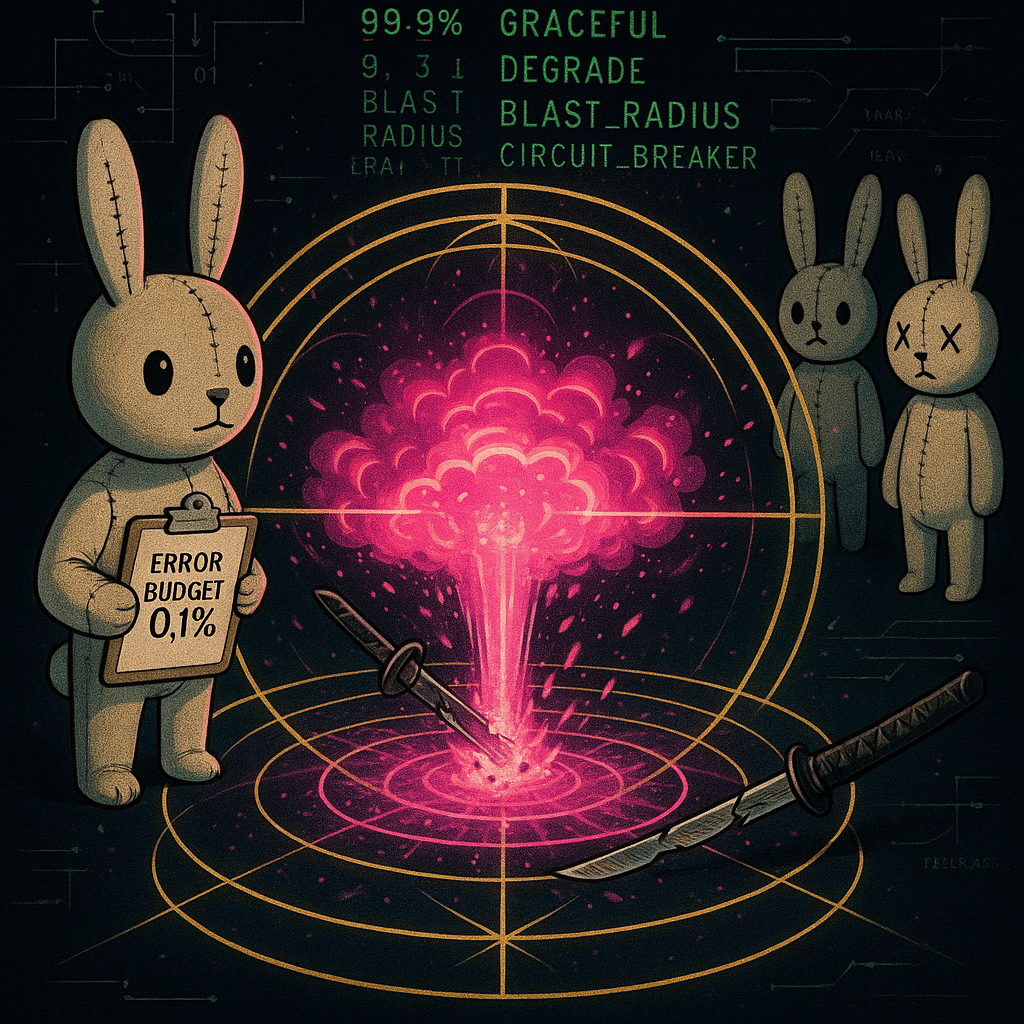

Blast Radius

When something fails, how much else fails with it? That's your blast radius. A well-isolated failure affects one component. A poorly-isolated failure cascades through the entire system.

Techniques for reducing blast radius: Bulkheads (isolated compartments that don't share fate). Circuit breakers (automatic disconnection when downstream systems fail). Timeouts (bounding how long you wait for something that isn't coming). Graceful degradation (offering reduced functionality instead of total failure).

Every dependency is a potential cascade path. Every synchronous call is a way for someone else's failure to become your failure. Blast radius design is the art of cutting these paths—accepting that failures will happen, but refusing to let them propagate.

Error Budgets

SRE introduced a counterintuitive concept: an error budget. If your SLO is 99.9% availability, you're allowed 0.1% downtime. That's your budget. You can spend it.

Budget healthy? Ship faster, take risks, run experiments—you have room to fail. Budget exhausted? Freeze features, focus on reliability, pay down technical debt. The budget creates a dynamic balance between velocity and stability.

This reframes the relationship between development and operations. It's not dev wanting to ship versus ops wanting stability. It's a shared budget they both manage. Spend it well.

Redundancy's Double Edge

The intuitive response to failure risk is redundancy. Two servers instead of one. Three data centers. Backup everything.

But redundancy adds complexity. Complexity causes failures. Your backup system is another system that can fail—and now you have failure modes in the backup itself, plus failure modes in the switchover, plus failure modes in the monitoring that detects when to switch.

Redundancy is necessary but not sufficient. Every redundant component is also a new failure mode. The art is adding enough redundancy to survive failures without adding so much complexity that you cause new ones.

"Everything fails, all the time." — Werner Vogels, CTO of Amazon

The Application: Failure Engineering for Humans

These principles aren't just for servers. They're for any complex system you're part of—including yourself.

Cognitive load budgets. You have limited error budget for decisions. Every decision depletes it. High-stakes decisions when budget is exhausted lead to failures. Design your day so critical decisions happen when budget is full. Routine decisions should be automated or habituated—don't spend budget on what doesn't need it.

Blast radius for commitments. When you fail at something (and you will), how much else fails with it? If every commitment is interconnected—one missed deadline cascading through all your projects—your blast radius is enormous. Isolate commitments. Build bulkheads between life domains. A failure at work shouldn't detonate your relationships.

Graceful degradation for energy. What's your reduced-functionality mode? When you're depleted, sick, or overwhelmed, what still works? Design a minimal operating mode—the essentials that keep running when everything else has to stop. You can't prevent depletion. You can design for it.

Circuit breakers for relationships. When a relationship is failing, do you have automatic disconnection before it cascades into everything else? Boundaries are circuit breakers. They prevent one struggling relationship from taking down your entire social system.

The Through-Line

The systems that survive aren't the ones that never fail. They're the ones that fail well. Contained blast radius. Measured error budgets. Graceful degradation. Quick recovery.

This requires a psychological shift. Stop treating failure as aberration. Start treating it as a design parameter. The question isn't "how do I prevent this from failing?" It's "when this fails—because it will—what should happen?"

Design for failure, or failure will design your disasters for you.

Substrate: Site Reliability Engineering (Google), Chaos Engineering (Netflix), Normal Accident Theory (Perrow)