Eleanor Guthrie: Platform Power and the Merchant Class

Part 7 of 13 in the Black Sails: A Leadership Masterclass series.

Eleanor Guthrie doesn't sail. Doesn't fight. Doesn't chase ships or seize cargo or do any of the things the show makes you think pirates do.

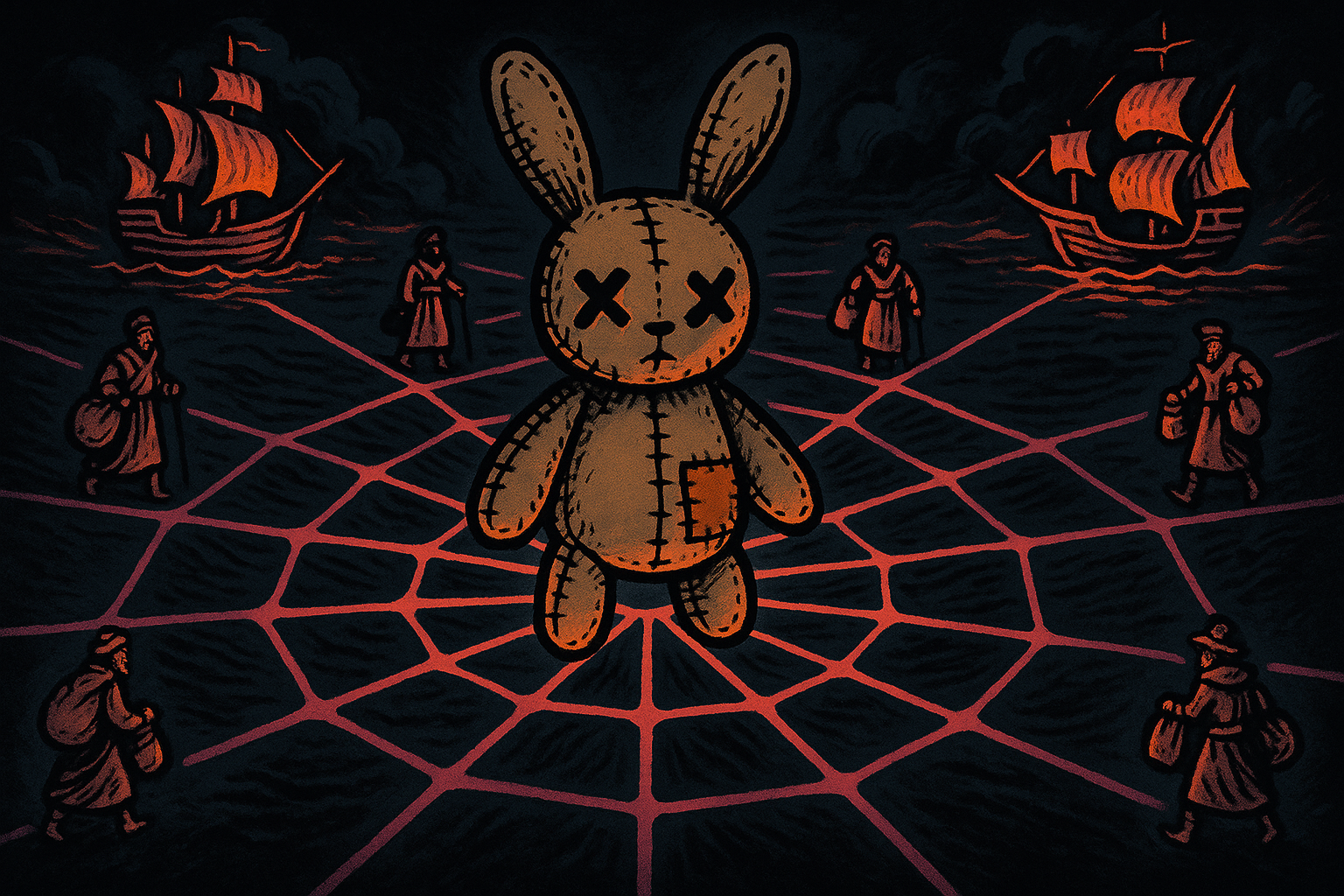

She runs the port.

This distinction matters more than anything else in Nassau's economy. While captains like Flint and Vane compete for glory and Teach builds his reputation and Silver plots his survival, Eleanor is building something structural. She's not in the piracy business. She's in the infrastructure business that makes piracy possible.

Every pirate who takes a prize needs somewhere to sell it—stolen goods don't move through legitimate markets. Every ship that needs supplies needs somewhere to provision. Every captain who wants to operate out of Nassau needs Eleanor's blessing, Eleanor's infrastructure, Eleanor's network of colonial merchants who don't ask questions.

The pirates think they're the power because they have the guns. Eleanor knows she's the power because she has the choke point.

She's not a pirate. She's the platform. And the platform extracts rent from everything that flows through it.

This is AWS. This is the App Store. This is Stripe. This is every piece of infrastructure that becomes load-bearing for an ecosystem.

The sellers do the work; Amazon takes the cut. The developers build the apps; Apple takes 30%. The pirates risk their lives seizing cargo; Eleanor takes her percentage.

The people doing the primary activity feel like the innovators. The platform extracts the rent.

Eleanor figured this out two hundred years before Silicon Valley. She understood that violence needs economics, economics needs infrastructure, and whoever controls infrastructure controls everything that depends on it.

Platform economics in 1715. Hiding in a pirate show.

Here's why platform power is so durable: switching costs. A pirate crew could theoretically sell their cargo somewhere else. But where? The legitimate markets won't touch stolen goods. Other ports lack Eleanor's network of buyers. Her relationships with colonial merchants—the people willing to turn a blind eye for the right price—took years to build. They trust her. They don't trust random pirates.

So the pirates have options in theory, zero options in practice. This is lock-in without contracts. Eleanor doesn't need legal enforcement when economic reality does the work for her.

The platform operator who controls critical infrastructure doesn't need to be the best at anything except being necessary. Eleanor isn't the smartest person in Nassau. She's just the person no one can work around.

Here's the vulnerability nobody sees until it's too late: everyone hates the toll booth.

The pirates use Eleanor but resent the extraction. Flint sees her as a resource. Vane sees her as a complication. The crews see her as the person who takes a cut from their labor.

The British tolerate her but don't respect her. She's useful as long as she's useful. The moment she's not, she's disposable.

Even Max—the person Eleanor was closest to—ends up taking her position. Not through love or loyalty. Through recognizing that Eleanor's platform is vulnerable and being ready when it falls.

This is the platform operator's loneliness. You're essential but not loved. You're the infrastructure everyone depends on and everyone resents. If they could route around you, they would. You know it. They know it. The relationship is pure dependency with no gratitude.

Eleanor keeps expecting recognition, loyalty, appreciation. She doesn't get it. Platforms don't get love. They get used.

The psychology of this position warps people. Eleanor starts believing she deserves gratitude—that providing essential services should earn her respect, loyalty, maybe affection. It doesn't. The more essential you become, the more you're taken for granted. Like plumbing. Like electricity. Like AWS when it's working.

You only notice infrastructure when it breaks. The rest of the time, you resent paying for it.

This creates a trap: Eleanor tries harder to prove her value. Provides more services. Takes more risk. Invests more in the ecosystem. And the more she invests, the more entitled everyone feels to her services, and the less they appreciate the provision.

She's giving more and receiving less recognition. This is the platform operator's death spiral—trying to earn love from people who will only ever see you as plumbing.

Eleanor's tragedy is that she tries to convert platform power into institutional power.

She marries into the British system. Becomes respectable. Trades her position as pirate queen for position as colonial wife. She's trying to legitimize—lock in her gains by joining the winning team.

It destroys her.

The platform worked because it was outside the system. Eleanor's value was that she could connect the illegitimate economy to the legitimate one. She was the bridge. When she crosses the bridge—when she becomes fully legitimate—she loses the position that made her valuable.

The pirates won't trust her now. The British never fully accept her. She's neither fish nor fowl. The platform operator who tried to become an institution loses both.

Watch how quickly it unravels. The moment Eleanor signals she's choosing legitimacy, the pirates start routing around her. They find new buyers. They work with Max, who stays in the gray area Eleanor abandoned. Eleanor's trying to build bridges to the empire while her actual business crumbles behind her.

Meanwhile, the British see her history. See what she built. See who she worked with. They don't see a valuable ally. They see someone who profited from chaos they're now trying to end. Her past isn't an asset to be leveraged—it's a liability to be contained.

She ends up in the worst position: too legitimate for the illegitimate economy, too illegitimate for the legitimate one. The platform operator needs to straddle that line. Eleanor tried to step off it. The line was the only place she could stand.

This is the classic legitimacy trap. Platform operators exist in gray areas—legal enough to function, illegitimate enough to serve illegitimate customers. The moment you legitimize fully, you can't serve the customers who made you powerful. The moment you stay fully illegitimate, the legitimate system can crush you.

Eleanor tries to resolve this tension by joining the empire. She thinks she can bring her platform with her—that the British will let her keep operating if she's one of them now. She's wrong. The British don't want her platform; they want the space where her platform operates. They want to replace her, not partner with her.

This is what happens to every platform that tries to legitimize: you become a competitor to the system you're trying to join. The system doesn't absorb you. It absorbs your market position and discards you.

The correct move—the move Max makes—is to stay in the gray area permanently. Never legitimize enough to trigger regulatory capture. Never go so dark that the state has to crush you. Maintain the ambiguity that lets you operate.

This requires giving up respectability. Eleanor wanted both—wanted to be the merchant queen and be respected by British society. You can't have both. The platform position requires accepting that you're the person who makes unsavory things possible. The moment you need social approval, the platform becomes a liability rather than an asset.

Eleanor should have stayed in the gray area. That was her defensible position. The moment she chose sides, she became disposable to both.

Then Woodes Rogers arrives. And this is the part tech platforms are learning right now.

Rogers doesn't compete with Eleanor's platform. He asserts that the crown owns the platform. Always did. Eleanor was a temporary license holder; the license is now revoked.

This is what happens when platforms meet states. The state has legitimacy. The state has force. The state can simply declare that it's taking over.

You can't route around state power the way you can route around market power. The state makes the rules about rules. When the state decides your platform is a problem, your platform is a problem. When the state decides it wants your infrastructure, it takes your infrastructure.

Eleanor's attempt to ally with the state—to marry into it, to become part of it—was an attempt to avoid this fate. If she's on the state's side, maybe the state won't take her platform.

Doesn't work. The state takes the platform anyway. It just takes Eleanor too.

The mechanism is elegant in its brutality. Rogers arrives with pardons. Any pirate can surrender and rejoin civilization. This splits Eleanor's customer base. The pirates who want out take the deal. The ones who stay are now criminals in open rebellion—which makes Eleanor's continued service to them treason rather than commerce.

Her platform is criminalized overnight. Not through competition—through reclassification. What was gray-area business yesterday is sedition today. The rules changed. The rule-makers changed them. Eleanor has no recourse because platforms have no sovereignty.

This is the lesson crypto platforms, payment processors, and marketplace operators keep learning: regulatory risk isn't just a line item. It's existential. When governments decide your platform enables bad actors, your platform ends. Not gradually. Immediately.

Eleanor built something real. It worked. It generated value. None of that matters when the sovereign arrives. Sovereignty beats platforms. Every time.

Eleanor understood platform economics two hundred years before we had the word. She just didn't understand it well enough to survive.

Platform power is real. Controlling infrastructure is controlling the ecosystem. Everyone who uses the platform depends on the platform.

Platform power is contingent. It exists at the pleasure of the system around it. It requires that no alternatives emerge, that users don't coordinate, that regulators don't regulate. These conditions can change.

Platform power is lonely. Nobody loves the toll booth. Gratitude goes to the people who create value, not the people who extract rent.

Platform power doesn't transfer. Trying to legitimize—to turn platform position into institutional position—often destroys both.

There's a fifth lesson Eleanor's arc teaches: platform power decays from within. Even before Rogers arrives, Eleanor's position is eroding. Max learns how the platform works by working inside it. Other merchants see Eleanor's margins and want them. The pirates resent the extraction and look for alternatives.

The platform operator's advantages are information asymmetry and relationship monopoly. Both decay over time. Information spreads. Relationships can be copied. The longer you run the platform, the more people understand how it works, and the easier it becomes to replicate.

Eleanor's mistake was believing platform position was permanent. It's not. It's a temporary monopoly on coordination that decays unless you're constantly reinforcing it. She spent too much energy trying to legitimize and not enough defending the position that made legitimization possible.

By the time Rogers arrives, her platform is already weakened from within. He doesn't crush a strong position. He takes a deteriorating one.

Eleanor Guthrie: pioneer of platform economics, victim of platform economics.

The infrastructure play is powerful until someone decides to take the infrastructure. Or until the infrastructure operator forgets that power is something you hold, not something you have.

Previous: Jack Rackham: The Narrator Survives Next: Max: From the Bottom to Platform Control