DoorDash Kids Aren't Lazy—They're Friction-Optimized

DoorDash Kids Aren't Lazy—They're Friction-Optimized

Your grandparents drove forty-five minutes to a restaurant, waited an hour for a table, and called it a nice evening. Your parents hit the McDonald's drive-through in twelve minutes and felt efficient. Your kid opens an app, taps twice, and food materializes at the door while they continue doing whatever they were doing.

Three generations. Same need. Radically different friction tolerance.

And somehow we've decided the kid is the problem.

The Friction Collapse Is a Feature, Not a Bug

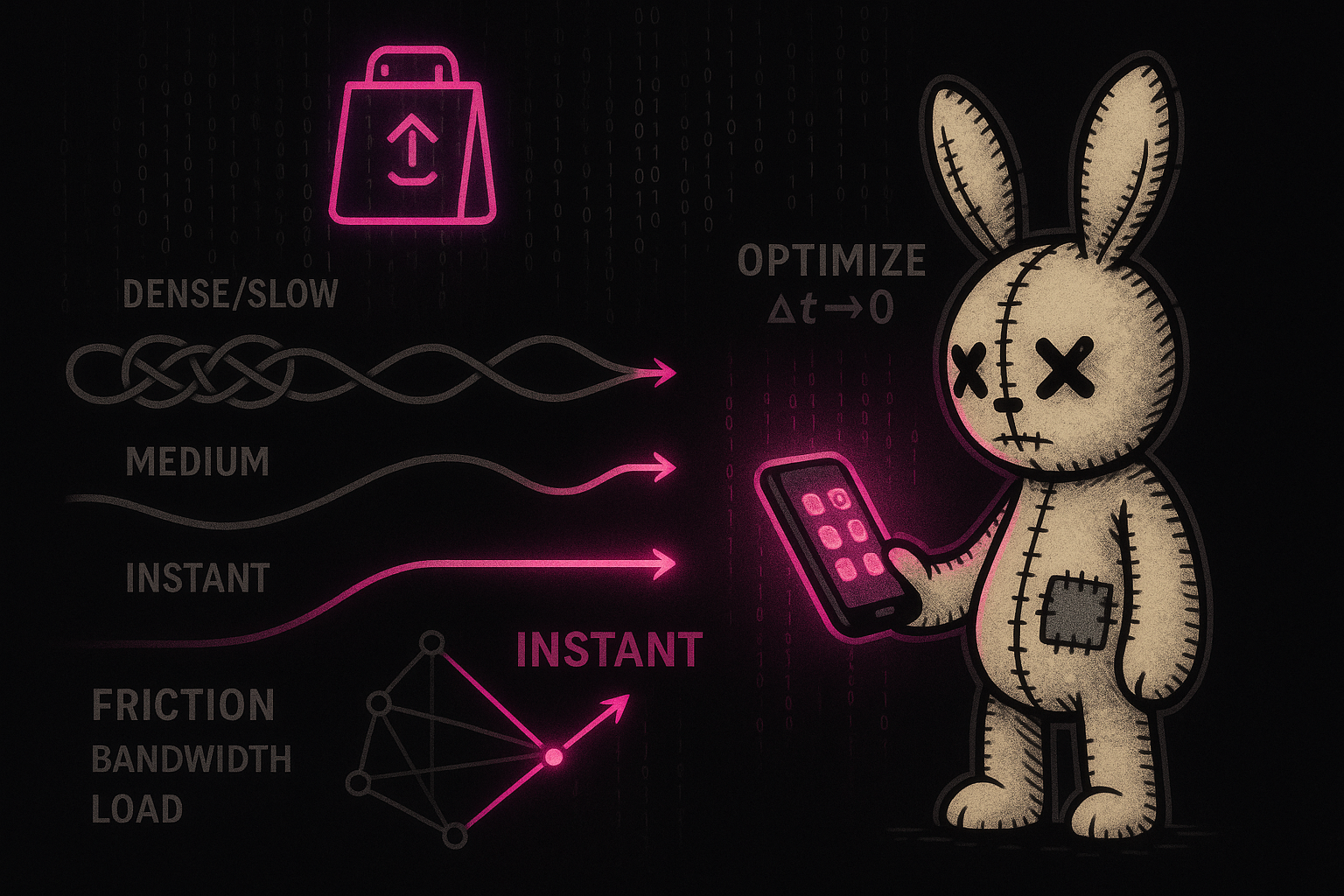

Every generation optimizes for cognitive load. This isn't new. What's new is the pace.

Your grandparents' leisure required planning, travel, waiting, social performance. The restaurant wasn't just food—it was an event that consumed an entire evening's bandwidth. That made sense when bandwidth was cheap and options were limited.

Your parents traded experience for speed. Fast food wasn't laziness; it was adaptation to a world where both parents worked and time became the scarce resource. The drive-through was a rational response to constraint.

Your kid? They're not trading anything. They're just... not paying the friction tax at all. The app handled it. The algorithm optimized the routing. The gig worker absorbed the travel. From your kid's perspective, food appears with roughly the same cognitive cost as opening the refrigerator.

This isn't decay. It's continued optimization along the same vector every generation has followed.

Friction Was Never the Point

Here's what the "kids these days" crowd misses: friction was never a virtue. It was a cost.

Nobody drove forty-five minutes to the restaurant because driving was good for them. They did it because that's what getting food required. The experience was a side effect of the friction, not the goal.

When we romanticize the friction—"we had to work for things"—we're confusing the tax with the value. It's like saying kids today don't appreciate music because they don't have to flip the record. The inconvenience wasn't the point. The music was.

Your kid figured out how to get the value without paying the cost. That's not laziness. That's intelligence applied to constraint removal.

The Economy Trained Them for This

This is the part that makes the "lazy" framing absurd: the entire economy has been optimized to reduce friction. That's what the last twenty years of tech investment accomplished.

- Amazon didn't win because people wanted more steps between wanting something and having it

- Uber didn't disrupt taxis by adding complexity

- Netflix didn't beat Blockbuster by making you drive somewhere

- Every successful platform of the last decade has the same value proposition: fewer steps, less waiting, reduced cognitive load

We built an entire economy around friction removal, deployed it at scale, and then act surprised when kids raised in that economy have low friction tolerance.

They're not broken. They're calibrated to the environment we built for them.

What Looks Like Laziness Is Actually Bandwidth Reallocation

Watch what your kid does with the time they didn't spend on friction.

They're not staring at walls. They're managing multiple Discord servers, maintaining streaks across platforms, navigating social dynamics more complex than most office politics, and context-switching between attention demands that would have overwhelmed any previous generation.

The bandwidth they save on food acquisition goes somewhere. Usually toward the thing the economy actually rewards now: managing information flow, maintaining social presence, and navigating algorithmic attention markets.

You might not value what they're doing with that bandwidth. But that's a different argument than "they're lazy."

The Real Question Isn't "Why Won't They Do Hard Things?"

The question is: what constitutes a "hard thing" in their environment?

For your grandparents, getting dinner was genuinely hard. It required planning, resources, social navigation. The friction was the challenge.

For your kid, getting dinner is trivially easy. The hard things are elsewhere: managing parasocial relationships, curating identity across platforms, dealing with infinite optionality, processing more information in a day than your grandparents saw in a month.

They're not avoiding hard things. They're solving different problems. The problems that their environment presents as challenges.

The Friction-Tolerance Mismatch

Here's where it gets uncomfortable for parents: your kid's friction tolerance is calibrated to a world that exists, while your expectations are calibrated to a world that's receding.

When you say "just call them," you're asking them to accept friction that, in their world, is entirely unnecessary. Texting accomplishes the same goal with less overhead. Your insistence on the phone call isn't teaching them a skill—it's teaching them to pay costs that don't need to be paid.

When you say "go to the store," you're asking them to spend time and cognitive load on logistics that an app handles in seconds. Unless you're teaching them something about the store—negotiation, physical selection, social interaction—the trip itself is pure friction.

The question isn't whether friction-tolerance is valuable. It's whether the specific friction you're insisting on teaches anything applicable to the world they'll actually inhabit.

What This Means for Parenting

None of this means friction is never valuable. Sometimes the friction is the point:

- Learning an instrument requires friction (that's where the skill develops)

- Physical training requires friction (that's what builds capacity)

- Deep relationships require friction (that's how trust forms)

The distinction is between friction-as-cost and friction-as-training. Driving to the restaurant was friction-as-cost. It didn't build anything. It was just the price of the thing you actually wanted.

The parenting move isn't "reintroduce friction everywhere." It's "identify which friction is actually developmental and which is just nostalgia for inconvenience."

Your kid shouldn't have to walk uphill both ways in the snow. But they probably should learn to do things that are hard on purpose, for the purpose of building capacity.

The DoorDash thing isn't the battle worth fighting.

The Optimization Will Continue

Your grandkids will look at your kids' friction tolerance and find it quaint. "You had to open an app? And wait twenty minutes?"

The direction is set. Friction reduction is what technology does. The question for every generation isn't "how do we go back" but "what do we do with the bandwidth we've freed up?"

Your kids aren't lazy. They're just the first generation to take the friction collapse for granted.

What matters now is what they build with the cognitive space that opened up.

This is Part 5 of the Kids Are Alright series. Next: "The Avocado Toast Math Is Actually Correct."