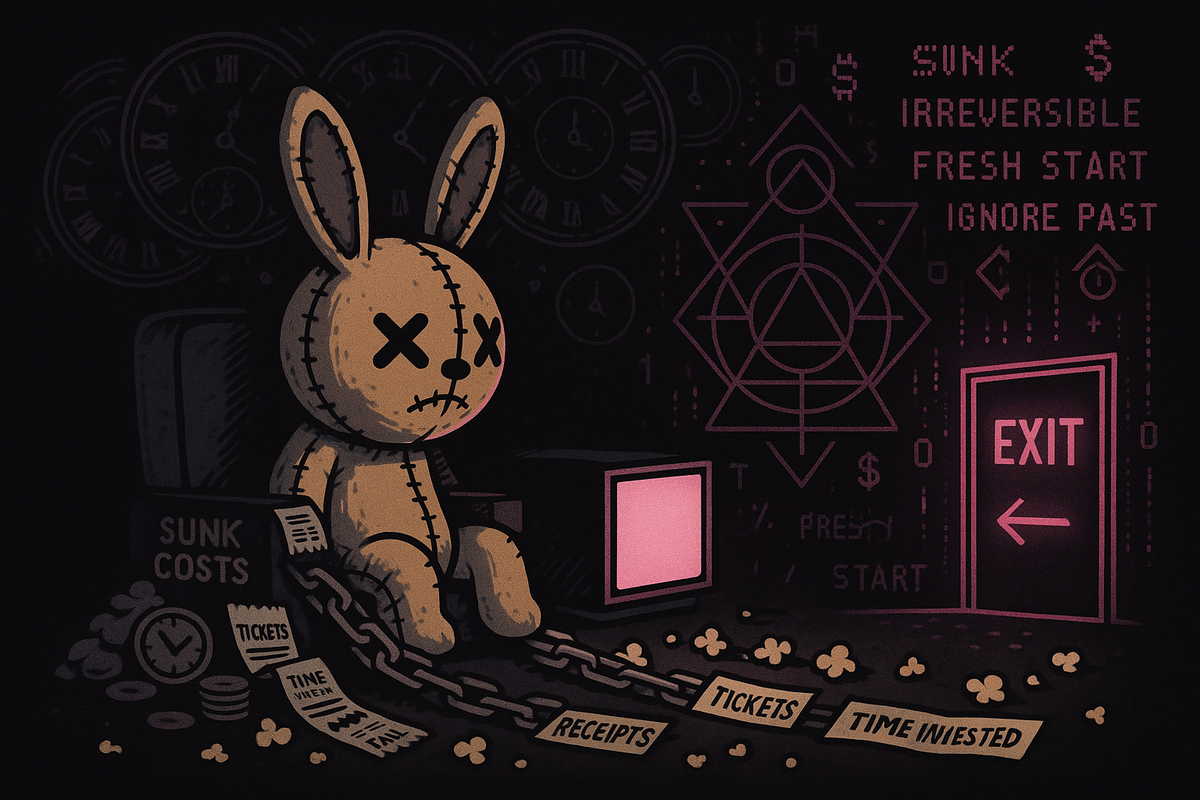

Don't Finish Bad Movies

Why do we finish terrible movies? The sunk cost fallacy keeps us trapped in bad jobs, failing relationships, and poor investments. Learn the cognitive science behind quitting smarter.

Why you stay in bad jobs, hold losing stocks, and keep reading books you hate—and how to stop

The movie is terrible. You knew it thirty minutes in. The plot is predictable, the dialogue is wooden, and you’re bored.

But you’ve already watched an hour. You paid for the ticket. You drove to the theater. You got the popcorn.

So you stay. You sit through another ninety minutes of mediocrity because leaving would mean “wasting” the time and money you already spent.

Except here’s the thing: that time and money is already gone. Whether you stay or leave, you don’t get it back. The only question is what you do with the next ninety minutes.

And you just spent them on a bad movie because of a cost that was already sunk.

The Fallacy

The sunk cost fallacy is continuing a course of action because of previously invested resources—time, money, effort, emotion—even when continuing is no longer the best choice.

The fallacy is treating past costs as relevant to future decisions. They’re not. Sunk costs are sunk. They cannot be recovered regardless of what you do next.

The rational question is always: “From this point forward, what’s the best use of my resources?” The past investment is irrelevant. It’s done. It’s not coming back.

But that’s not how it feels.

Why It Happens

Sunk cost fallacy is loss aversion’s cousin. You’ve already “spent” something, and walking away feels like losing it—like confirming that it was wasted.

Staying, continuing, doubling down—these feel like preserving the possibility that the investment will pay off. As long as you’re still in the game, the loss isn’t finalized. There’s still a chance it was worth it.

Walking away makes the loss real. And losses hurt. So you stay.

There’s also an identity component. Admitting the investment was a mistake means admitting you made a mistake. The longer you’ve been on a path, the more your identity becomes attached to that path. Leaving isn’t just abandoning a project—it’s abandoning a version of yourself.

Escalation of commitment, it’s sometimes called. The more you’ve invested, the harder it is to stop, because stopping means writing off everything you’ve put in.

The Question That Clarifies

Here’s the move. One question:

“If I were starting fresh today, with no history, would I make this same choice?”

Would you start watching this movie, right now, knowing what you know?

Would you take this job, today, knowing what you’ve learned?

Would you start this relationship, now, given what you understand about it?

Would you buy this stock, at this price, with this information?

If the answer is no—if you wouldn’t start this from scratch—then you’re only continuing because of what you’ve already spent. And what you’ve already spent is gone.

The past got you here. But the past can’t tell you what to do next.

Where This Gets Expensive

Careers. “I’ve been in this field for ten years. I can’t start over now.” But you’re not starting over—you’re starting from here, with ten years of skills and knowledge. The question is whether the next ten years are best spent continuing or pivoting. The past ten are sunk.

Relationships. “We’ve been together for so long. I can’t throw that away.” You’re not throwing it away. It happened. The question is whether the future you want is best pursued with this person or separately. The history is real, but it’s not a reason to continue if continuing isn’t right.

Investments. You bought a stock at $100. It’s now at $50. You hold, waiting to “get back to even.” But the stock doesn’t know your cost basis. The question is whether, at $50, it’s worth holding—not whether you’d feel bad selling at a loss. The loss already happened. Selling just makes it visible.

Projects. You’ve spent six months building something. It’s not working. But you’ve invested so much… The question is whether, starting now, the best use of your next six months is continuing this project or starting something else. The past six months are spent either way.

Education. “I’ve already done two years of this degree. I can’t quit now.” You’re not losing two years by changing direction. Those years are gone. The question is whether the next two years are best spent finishing this degree or doing something else.

The Mechanism

Here’s what’s happening computationally:

Your brain tracks investments. It maintains a mental ledger of what you’ve put into various projects, relationships, commitments. This tracking was adaptive—in the ancestral environment, quitting too easily meant losing the benefits of persistence.

The problem is that the tracking doesn’t distinguish between recoverable and unrecoverable investments. It just registers “I’ve put a lot into this,” and generates a feeling of aversion to abandoning it.

This made sense when most investments were partially recoverable. If you’d spent weeks building a shelter, the shelter was still there even if it wasn’t perfect. Abandoning it meant genuinely losing something tangible.

But many modern investments are purely sunk. Time is gone. Tuition is spent. The opportunity cost of staying is invisible to the mental ledger.

Your brain feels the explicit loss of “giving up” but doesn’t feel the implicit loss of continuing. So it pushes you to continue even when continuing is the worse choice.

The Tricky Part

Sometimes persistence is right. Sometimes the investment does pay off. Grit matters.

The sunk cost fallacy doesn’t say “always quit when things are hard.” It says “don’t let past investment be the reason you continue.”

Here’s the distinction:

Good reasons to continue: The project is still promising. You’re learning. The opportunity is still there. The relationship is worth fighting for. The work is meaningful.

Bad reasons to continue: I’ve already put so much in. I can’t have wasted all that. It would feel like admitting defeat. I’ve come this far.

Notice that the good reasons are all about the future—what continuing offers going forward. The bad reasons are all about the past—what you’ve already spent.

Past investment isn’t a reason to continue. It’s just a reason you’re here. What matters is what happens next.

The Move

When you feel the pull to continue something, ask why.

If your reasons are about the future—genuine opportunity, meaningful work, recoverable situation—those are real reasons. Continue.

If your reasons are about the past—time spent, money invested, identity attached—those aren’t reasons. Those are sunk costs pulling at you.

Then ask the fresh-start question: Would I begin this today?

If yes, continue. The past and the future both point the same direction.

If no, you’re being held by a ghost. The past is gone. You’re not getting it back. The only question is what you do with the time that remains.

Don’t finish bad movies.

This is Part 6 of Your Brain’s Cheat Codes, a series on the mental shortcuts that mostly work—and the specific situations where they’ll ruin you.

Previous: Part 5: Losing Hurts Twice As Much

Next: Part 7: Same Data, Different Decision — The Framing Effect