Disorder Is Relative to Environment

Disorder Is Relative to Environment

Here's a line that sounds like a joke but isn't:

"Alcoholism is when the drinker becomes unmanageable, not when the drinking becomes unmanageable."

The joke works because it points at something true: disorder is defined by dysfunction in context. The same behavior can be pathological in one environment and perfectly functional in another.

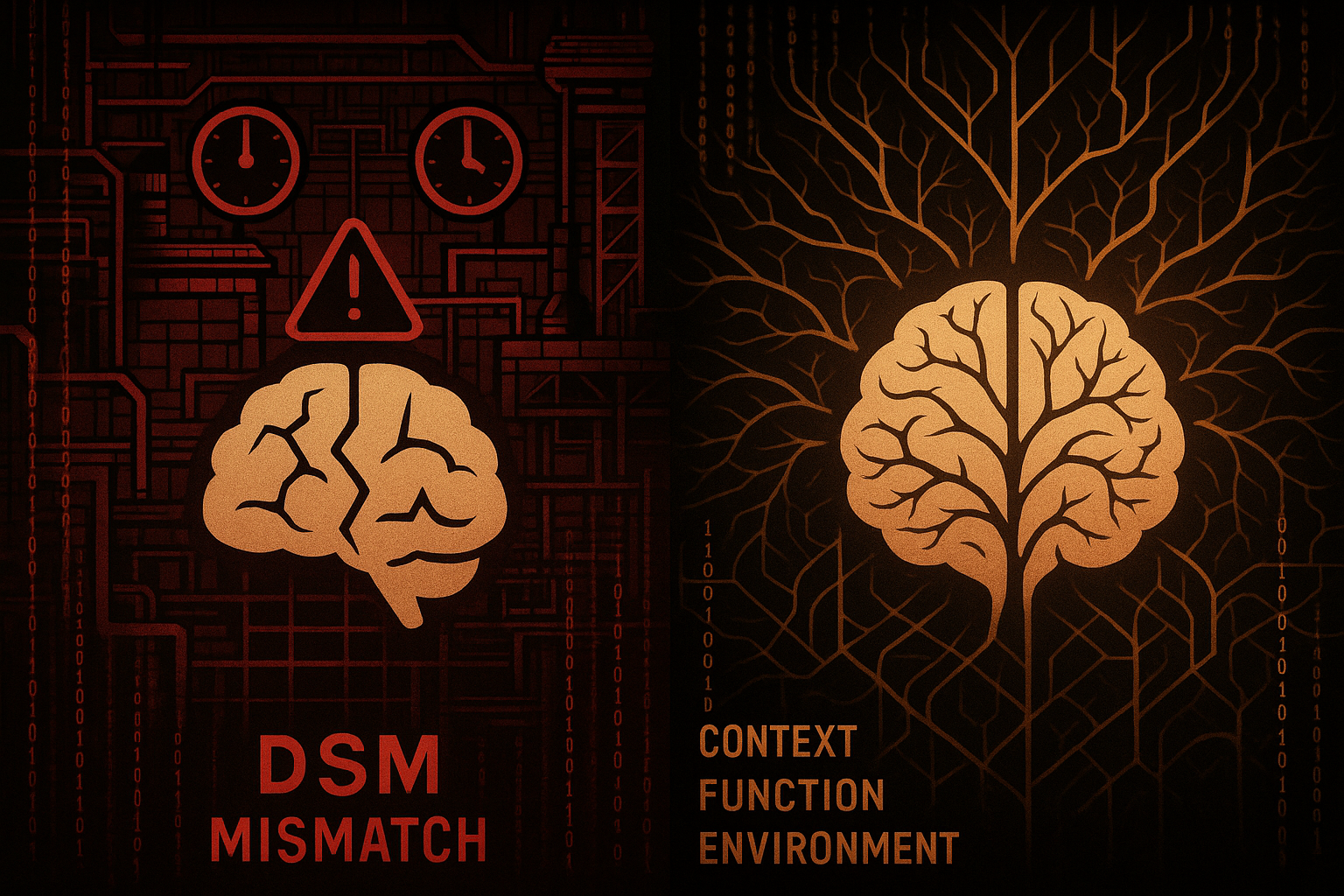

The DSM—the manual that defines mental disorders—doesn't diagnose based on brain states or blood tests. It diagnoses based on symptoms that cause "clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning."

Distress. Impairment. Functioning.

All of these are relative to environment. And when the environment changes radically, the definitions should change with it.

The Bus Stop Test

Consider reading.

A generation ago, sitting at a bus stop reading a book was unremarkable. Admirable, even. A sign of intellectual curiosity.

Today, sitting at a bus stop reading a physical book while ignoring your phone is almost... weird. Not checking your notifications. Not responding to messages. Not aware of what's happening in your various feeds.

In the current attention economy, sustained focus on a single offline object is increasingly non-functional. It doesn't integrate with how information flows, how social obligations are maintained, how opportunities arrive.

Is reading a disorder now? Of course not. But the point stands: what counts as "functional behavior" is relative to the environment in which you have to function.

ADHD as Environmental Mismatch

We've medicalized attention patterns that don't fit the current institutional environment—schools designed for industrial-era compliance, workplaces optimized for long-form focus—and called the mismatch a disorder.

But consider alternative environments where ADHD traits might be neutral or even advantageous:

- Emergency response: Rapid attention shifting, high stimulus tolerance, quick decisions under pressure

- Entrepreneurship: Comfort with chaos, ability to juggle multiple priorities, energy bursts for new projects

- Creative work: Divergent thinking, making unexpected connections, following tangents productively

- Hunting/gathering: Scanning for threats/opportunities, rapid context-switching, not getting locked into one focus

For most of human history, attention worked differently. The sustained, single-task focus that schools demand is an invention of the last few centuries—designed to produce factory workers and bureaucrats.

The kid who "can't focus" in class might focus fine in environments that match their attention pattern. The disorder isn't in the brain; it's in the fit between brain and environment.

Anxiety in Anxious Times

The DSM defines Generalized Anxiety Disorder as "excessive anxiety and worry" that the person finds difficult to control.

"Excessive" relative to what?

If you're a young person looking at climate projections, political instability, economic precarity, potential automation of your career, and a housing market that seems designed to exclude you—how much worry is "excessive"?

Some level of anxiety in response to genuinely uncertain and threatening conditions isn't disorder. It's accurate perception.

The pathologization of anxiety assumes a baseline level of environmental stability against which excess worry can be measured. When that baseline dissolves, the concept of "excessive" worry becomes harder to define.

This doesn't mean anxiety is never problematic. Anxiety that prevents functioning, that spirals into paralysis, that disconnects from actual threat levels—that's worth addressing.

But the kid who's anxious about the future might not have a disorder. They might be paying attention.

Depression in Disconnected Worlds

Depression rates among young people have increased dramatically. The standard explanation is "something's wrong with the kids."

Alternative explanation: something's wrong with the environment.

Humans evolved in tight-knit communities with clear social roles, physical activity built into daily life, exposure to nature, meaningful work, and stable relationships. Modern life—especially for young people—often provides:

- Weak and unstable social ties

- Sedentary existence

- Alienation from nature

- Work that feels meaningless

- Relationships mediated by algorithms

When you take an organism evolved for one environment and place it in a radically different one, symptoms emerge. Is that a disorder of the organism, or a feature of the mismatch?

Maybe depression is sometimes the brain's accurate signal that something is wrong with the situation, not the brain.

The Function of Diagnosis

This isn't to say diagnosis is useless. Diagnosis does important work:

- It provides access to accommodations (extra time, medication, support services)

- It offers a framework for understanding one's experience

- It reduces shame by locating the problem in biology rather than character

- It connects people to communities who share their experience

But diagnosis also does problematic work:

- It locates the problem in the individual rather than the environment

- It suggests the person needs to change, not the context

- It can become an identity that limits rather than liberates

- It medicalizes variations that might be neutral in different contexts

The question isn't "is this a real disorder?" The question is "what work is the diagnosis doing, and is that work useful?"

What This Means for Kids

When we diagnose kids at increasing rates—ADHD, anxiety, depression, spectrum conditions—we're making a claim: the problem is in the kid.

But the environment kids inhabit has changed more in the last two decades than in the previous two centuries. The social environment, the information environment, the economic environment, the attention environment—all radically different from what humans evolved with.

Before we conclude that kids are broken, we should consider whether the environment is what's broken, and the kids are just responding accurately.

The diagnostic frame says: this child has a disorder that impairs their functioning.

The environmental frame says: this child has traits that mismatch with their context, and either the traits or the context could change.

Same child. Same behaviors. Different implications.

The Reframe

Disorder is a relationship, not a thing.

It's the relationship between an organism's traits and an environment's demands. Change the environment, and the same traits can shift from disorder to neutral to advantageous.

When we see rising rates of diagnosis among young people, we can ask:

"What's wrong with the kids?"

Or we can ask:

"What's changed about the environment that's making normal human variation look like pathology?"

The second question is harder. It doesn't lead to a simple intervention. But it might be closer to the truth.

Your kid's "disorder" might be an accurate response to an environment that demands things human brains weren't designed to provide. That doesn't mean the traits aren't challenging. It means the challenge might be on both sides of the equation.

This is Part 7 of the Kids Are Alright series. Next: "Your Kids Are Training for Jobs That Don't Exist Yet."