Complexity 101: Emergent Beasts vs. Clockwork Toys

Human intuition fails catastrophically with complex adaptive systems. Understand emergence, feedback loops, attractors, and why typical problem-solving approaches backfire.

Why your intuition keeps betraying you—and what to do about it

The Betrayal

You've tried to fix something and made it worse. Resistance increased. The problem mutated. What worked last time exploded this time. You pulled a lever expecting A and got Z, sideways, on fire.

Then later—maybe in a different domain—you did nothing. Watched. The problem resolved itself. Not perfectly, but it found some equilibrium you couldn't have engineered if you'd tried for a decade.

Your intuition is lying to you. Not because you're stupid, but because it was trained on the wrong class of problems. Most of the shit that matters—relationships, organizations, markets, your own goddamn habits—belongs to a category your brain never evolved to handle. And until you can see the difference, you'll keep getting blindsided by systems that refuse to behave.

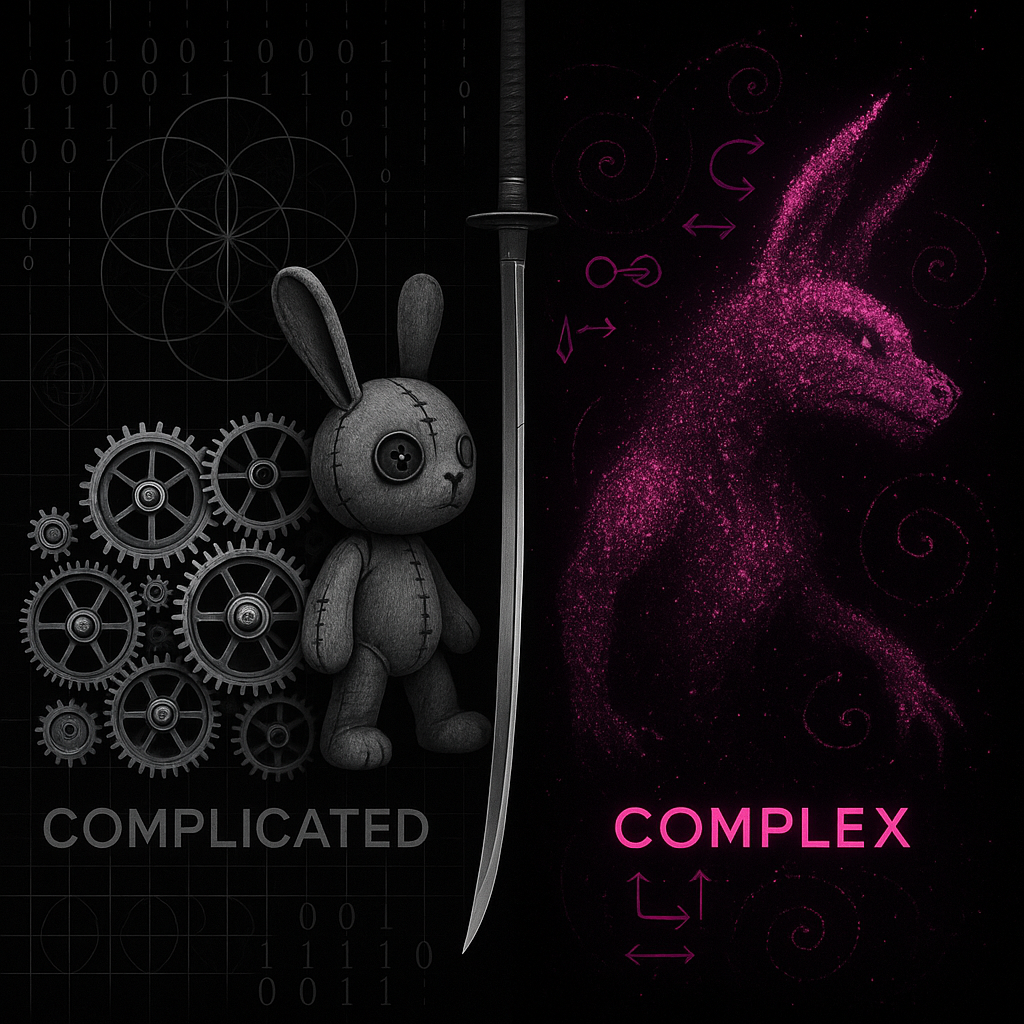

This is the complicated/complex divide. It's not academic taxonomy. It's the difference between systems you can control and systems you can only influence. Miss this distinction and you'll spend your life pulling levers that aren't connected to anything.

The Pattern: Clockwork vs. Beasts

Dave Snowden's Cynefin framework and the Santa Fe Institute's complexity science converge on the same fundamental insight: there are two radically different kinds of systems, and they require opposite approaches.

Complicated Systems (Clockwork)

A jet engine. The tax code. A Swiss watch. A thousand moving parts, intricate as hell, but ultimately traceable. You can disassemble them, understand each component, map the causal chains, predict the outputs. Expertise works. Analysis works. Given enough time and knowledge, you can master them completely.

The signature: if you understand the parts, you understand the whole. Causation is linear or at least linearizable. History doesn't matter much—the same inputs produce the same outputs regardless of path.

Complex Systems (Beasts)

A market. An ecosystem. A relationship. An organization. Your nervous system. These aren't just complicated—they're complex. The parts interact in non-linear ways. They adapt. They generate emergent properties that exist nowhere in the components. Understanding every part doesn't help you understand the whole, because the whole is a verb, not a noun.

The signature: the system behaves in ways no component intended. Small causes produce large effects (or no effects). Large interventions disappear without trace (or backfire catastrophically). History matters—the same inputs at different times produce different outputs. The beast has moods.

The Mechanism: Why Beasts Don't Behave

Three features make complex systems ungovernable by clockwork intuition: feedback loops, attractors, and emergence. This isn't metaphor. It's the mathematical structure of why your interventions keep failing.

Feedback Loops

Positive feedback amplifies change. A leads to more B, which leads to more A. Exponential growth. Exponential collapse. Tech debt is a positive feedback loop: shortcuts create complexity, complexity creates pressure, pressure creates shortcuts. Viral content works the same way—views create visibility, visibility creates views.

Negative feedback dampens change. Thermostats. Hunger-eating-satiation. These produce stability, homeostasis. But add delay to negative feedback and you get oscillation—overshoot, undershoot, overshoot. The market correction that over-corrects. The micromanager who under-manages after being told to back off, then over-manages again when things slip.

The intervention implication: you're never pushing on an isolated variable. You're pushing on a loop. And unless you know where you are in the loop, you can't predict whether your push will amplify, dampen, or trigger oscillation.

Attractors

Complex systems settle into patterns—regions of state-space they tend toward. A point attractor is a stable state (thermostat holding 70°F). A limit cycle is a stable oscillation (boom-bust). A strange attractor is chaotic but bounded (weather—unpredictable, but within ranges).

The brutal truth: interventions that don't change the attractor structure get undone. You push the system away from its basin, it rolls back. This is why org change initiatives fail—they perturb the system without reshaping what the system is attracted to. Six months later, same patterns, new jargon.

To create lasting change, you don't push—you reshape the landscape. Change what the system is attracted to, and it'll move itself.

Emergence

Emergence is what happens when component interactions generate system-level properties that exist nowhere in the components themselves. No neuron is conscious. No trader is a market. No employee is a culture. These properties appear at the system level through interaction patterns.

The design implication: you cannot mandate emergent properties. You cannot engineer culture by defining values. You cannot create innovation by scheduling innovation time. You can only shape the conditions from which the desired emergence might arise—and accept that it might arise differently than expected, or not at all.

"The system is not the sum of its parts. It's the product of their interactions." — Russell Ackoff

The Application: How to Work With Beasts

Knowing the theory is useless without deployment. Here's how the complicated/complex distinction changes your actual behavior:

Stop predicting, start probing. In complicated systems, you analyze then act. In complex systems, you act to learn. Small experiments. Safe-to-fail probes. You're not trying to get it right—you're trying to see how the system responds. Intervention as information-gathering.

Map the loops before pulling levers. When you feel the urge to fix something, stop. Ask: what are the feedback loops? Am I pushing on a positive loop (amplification risk) or negative loop (oscillation risk)? Where's the delay? Most problems aren't events with simple causes—they're loop symptoms. The intervention point is in the loop structure, not the symptom.

Shape conditions, not outcomes. You can't control emergence, but you can influence what emerges. Create the conditions for the attractor you want. Make the desired behavior the path of least resistance. This is slower than mandate. It's also the only thing that actually works.

Example: Tech Debt as Feedback Pathology. Tech debt spirals because it's a positive feedback loop with delay. Shortcuts → complexity → time pressure → shortcuts. The fix isn't heroic refactoring (perturbing the attractor). It's changing what the system is attracted to—build quality into the process, make shortcuts harder than doing it right, shorten the feedback loop between cause and consequence. You don't fight the beast. You change what the beast is hungry for.

The Through-Line

Your intuition was trained on clockwork. Most of what matters is beast. This isn't your fault—evolution didn't prepare us for systems that generate their own behavior, adapt to our interventions, and exhibit properties that exist nowhere in their parts.

But now you know. Complicated systems yield to analysis and expertise. Complex systems yield to probing and condition-shaping. The first step is always the same: look at the system you're trying to influence and ask the brutal question.

Is this a clockwork toy I can master? Or a beast I can only dance with?

Answer wrong, and you'll spend your life pulling disconnected levers. Answer right, and you'll stop fighting systems that were never going to submit—and start shaping the conditions from which your desired outcomes might emerge.

The beast doesn't care about your plans. But it does respond to its environment. Change that, and the beast moves itself.

Substrate: Complexity science (SFI), Cynefin framework (Snowden), Cybernetics (Wiener, Ashby)