Brene Brown and the Feminization of Therapy

Part 8 of 9 in the Toxic Masculinity in 2026: A Field Guide series.

Brené Brown told the world that vulnerability is strength.

She wasn't wrong. Her TED talk has fifty million views because it resonated. The research is real. The insight is genuine. Vulnerability does enable connection. Shame does corrode wellbeing. The armor we build does isolate us.

And.

The therapeutic culture that emerged from this insight has a gender problem. Vulnerability has been universalized as virtue when it's actually a gendered strategy. The way women process emotion became the way everyone should process emotion. What helps women often doesn't help men.

This isn't an MRA complaint. This isn't "men are the real victims." It's a genuine question about whether contemporary therapy recognizes different legitimate processing styles—or whether it pathologizes male psychology while treating female psychology as default.

I don't know the answer. But the question is worth asking.

The Brené Brown Framework

Brown's work emphasizes:

Vulnerability. Showing yourself without armor. Revealing uncertainty, emotion, need. Letting yourself be seen.

Shame resilience. Recognizing shame, talking about it, processing it through connection.

Emotional expression. Naming feelings, discussing feelings, sharing feelings with trusted others.

Connection. Relationships as the site of healing. Isolation as the problem; belonging as the solution.

This framework is genuinely helpful for many people. It's research-based. The outcomes are positive. The approach works.

The question is: does it work equally well for everyone?

Processing Differences

Men and women, on average, process emotion differently.

This isn't essentialism—it's observation. Individual variation is enormous. Plenty of men are verbal processors. Plenty of women are action-oriented. But population-level patterns exist, and they matter for how we structure support.

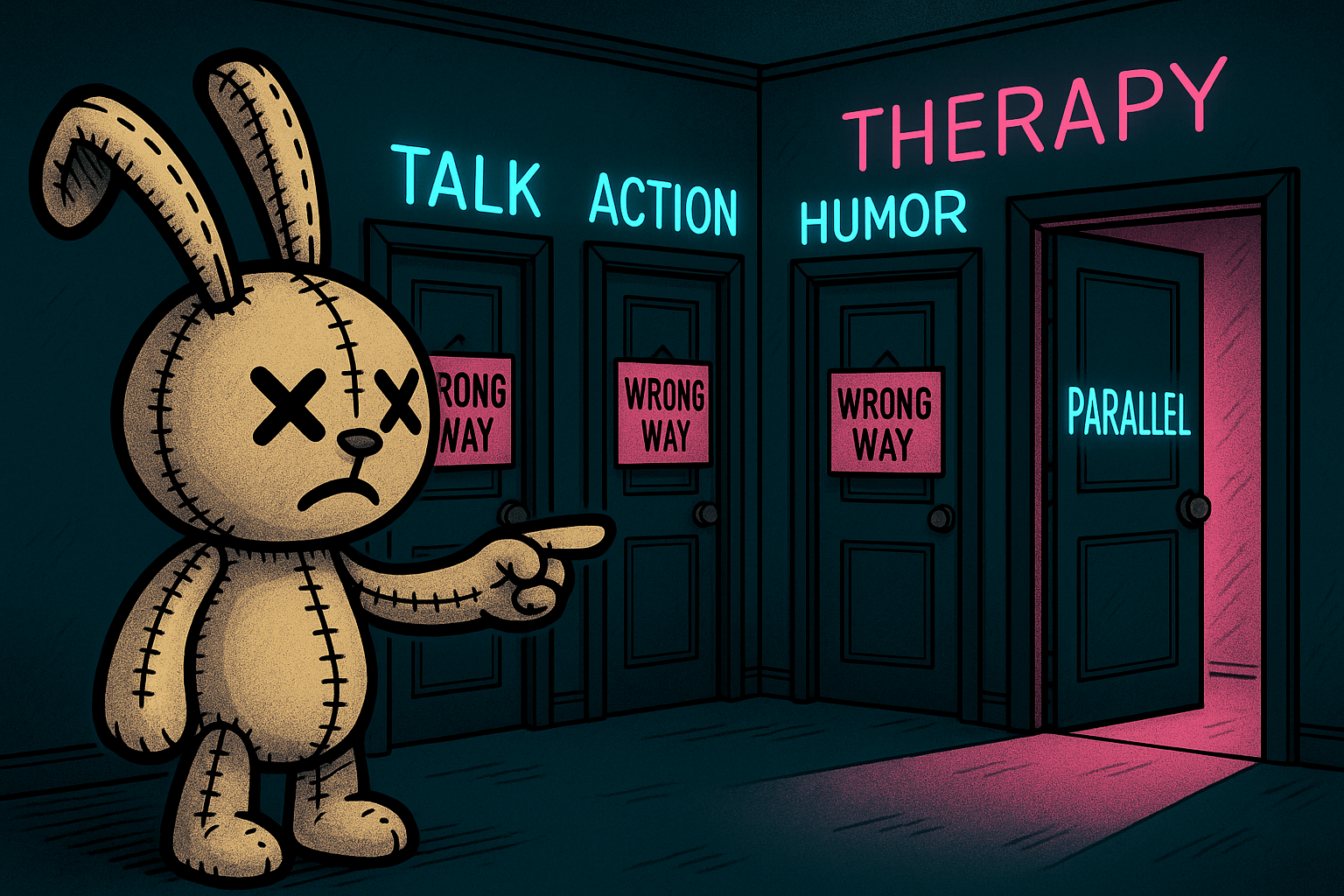

Men tend toward: Action-based processing. Doing something about the problem. Parallel activity while talking (walking, driving, working together). Humor as connection and release. Problem-solving orientation.

This shows up consistently. The man who processes best while shooting basketball with a friend. Who opens up in the car, side-by-side, not making eye contact. Who uses jokes to approach painful topics—not to deflect, but because humor is how he metabolizes pain. Who needs to be doing something with his hands while talking about hard things.

The action isn't avoidance—it's the container that makes processing possible. Remove the action and you remove the safety. Ask him to sit still, make eye contact, and verbally process, and he shuts down. Not because he's resistant, but because that's not his entry point.

Women tend toward: Verbal processing. Talking through the emotion. Face-to-face connection. Empathy and validation before solutions. Relationship as the primary container for processing.

This also shows up consistently. The woman who needs to talk through what happened, often multiple times, before she knows how she feels about it. Who values face-to-face presence. Who experiences problem-solving suggestions as dismissive—she's not asking for solutions, she's processing through narration. Who uses relationship as the place where emotion gets metabolized.

The talking isn't performative—it's how the processing happens. The verbal narration is the work, not a prelude to work. Sit with her, listen, validate, and the emotion moves through. Offer solutions too quickly and you interrupt the process.

Neither is superior. Both are legitimate. The question is whether contemporary therapy treats them equally.

The question is also: where do these differences come from? Some is probably biological—testosterone correlates with action-orientation, estrogen with relational-orientation, though effects are modest. Some is definitely cultural—boys socialized to solve problems, girls socialized to discuss feelings. Individual variation swamps the population patterns.

But the patterns exist. And if therapy is designed around one pattern, it will serve people who match that pattern better than people who don't.

The Therapeutic Default

Mainstream therapy—the kind most people encounter—has a processing style.

Sit across from each other. Make eye contact. Talk about feelings. Name emotions. Process verbally. Connect through disclosure.

This is female-typical processing. It works well for people whose psychology matches. For others, it's awkward, unnatural, effortful in ways that may not be productive.

The man who processes best while shooting hoops with a friend. The man who opens up while driving, not face-to-face. The man who uses humor to approach painful topics. The man who needs to do something before he can discuss something.

Is therapy structured for him? Or does therapy ask him to process like someone he isn't?

What Gets Pathologized

Consider what gets labeled as resistance or avoidance:

Using humor. "You're deflecting with jokes." But humor is a genuine processing tool. Some people approach pain through levity. Pathologizing this may prevent authentic processing.

Wanting to fix it. "You're jumping to solutions." But solving the problem is how some people process emotion about the problem. The action is the processing.

Preferring parallel activity. "You need to sit with it." But some people access emotion better while doing something. The activity creates safety.

Needing space. "You're withdrawing." But processing often requires consolidation. Going away to come back integrated.

These patterns are more common in men. They're often treated as failures to engage rather than different modes of engagement.

The Vulnerability Problem

Vulnerability is the core virtue of contemporary therapeutic culture. Show yourself. Be seen. Drop the armor.

For women, vulnerability often leads to support. She cries; she's comforted. She admits struggle; she's validated. She shares that she's overwhelmed; people help. Vulnerability activates caregiving in others. The cultural script is: woman shows vulnerability → others respond with support.

This isn't universal, but it's common enough to be reliable. Women learn they can be vulnerable and generally receive support for it. The strategy works often enough to be reinforced.

For men, vulnerability often leads to loss. He cries; his partner feels burdened or loses attraction. He admits struggle; his status drops. He shares that he's overwhelmed; people wonder why he can't handle it. Vulnerability can activate contempt rather than care. The cultural script is: man shows vulnerability → others lose respect.

This shows up in research. Women often report wanting male partners to be emotionally open. Men attempt emotional openness. Women respond with some combination of discomfort, loss of attraction, or criticism. The man learns: vulnerability is punished, not rewarded. Better to keep the armor on.

This isn't universal. Healthy relationships support male vulnerability. Secure women can hold space for male emotion without losing attraction or feeling burdened. But the population-level pattern matters: vulnerability isn't equally safe across genders.

Brené Brown's research is based largely on women's experiences. Women in her studies who practiced vulnerability reported better relationships, more connection, less shame. The findings are real. But they may not generalize across gender.

Telling men to be vulnerable without addressing the contexts that punish male vulnerability is incomplete advice. It universalizes a strategy that works better in some social contexts than others.

The man who follows the advice, tries vulnerability, gets burned—he doesn't conclude "I need to find better people." He concludes "vulnerability is a trap." And the therapeutic culture that told him to be vulnerable has no good response. If it goes badly, the problem must be him—he did it wrong, or he's with the wrong person, or he needs to work on himself more.

The alternative hypothesis—that vulnerability has different costs and benefits depending on gender—rarely gets considered. Because that would mean the universalized framework isn't universal.

The Therapy Pipeline

Who becomes a therapist?

People drawn to emotional work. People who value processing, connection, verbal expression. People whose own psychology responds well to therapeutic frameworks.

These are, disproportionately, women. Not exclusively—there are many excellent male therapists. But the profession skews female.

This creates a feedback loop. The people designing therapy are the people who respond well to therapy as currently designed. The frameworks feel natural because they match the designers. Differences in processing style become deficits to correct rather than variations to accommodate.

What Would Change

If therapy took male processing seriously:

More action-based modalities. Working while talking. Walking sessions. Activity as container for conversation.

Less emphasis on emotional disclosure as the metric. Progress measured by function and wellbeing, not by amount of feeling expressed.

Humor as valid processing. Not deflection to overcome, but genuine approach to pain.

Problem-solving as processing. Doing something about the problem is engaging with the emotion about the problem.

Different relationship to vulnerability. Recognizing that vulnerability has different costs in different contexts.

Some therapists do this. Some modalities accommodate different processing styles. But the mainstream cultural message—Brené Brown, the TED talks, the pop psychology—emphasizes the verbal-disclosive-vulnerable framework as universal.

The Both/And

This isn't "Brené Brown bad, traditional masculinity good."

Traditional masculinity has problems. Emotional suppression. Inability to ask for help. Disconnection that leads to isolation. Inability to admit weakness. Many men are genuinely harmed by the armor they've built. They die younger, die more from suicide, suffer more from social isolation, struggle to form intimate friendships.

The armor is real and it causes real harm. The man who can't admit he's struggling, can't ask for support, can't process grief or fear or vulnerability—he's cut off from huge domains of human experience. That's a problem.

And.

The solution isn't to impose a different processing style. The solution is to expand therapeutic capacity. To recognize multiple legitimate ways of engaging with emotion. To stop treating female-typical processing as the correct processing that men need to learn.

Maybe the man who processes through action isn't avoiding emotion—maybe he's processing emotion through the modality that works for his nervous system. Maybe the humor isn't deflection—maybe it's a legitimate approach to pain. Maybe the side-by-side conversation in the car is more intimate for him than face-to-face disclosure in a therapy office.

Maybe some men need to learn to be vulnerable. The men who've armored so completely they can't access their own inner life—yes, they need to learn vulnerability. They need to soften the armor enough to let experience in.

Maybe some therapy needs to learn to meet men where they are. To structure sessions around activity when that's what works. To validate humor as genuine processing. To stop pathologizing action-based coping and recognize it as different, not deficit.

The both/and is hard to hold. It requires believing simultaneously that traditional masculinity causes harm and that therapeutic culture has blind spots about male psychology. That men need to change and that therapy needs to change. That vulnerability matters and that vulnerability has gendered costs we're not accounting for.

This is more complex than the standard narrative. The standard narrative is simple: men are emotionally shut down, therapy teaches emotional openness, problem solved. This narrative says: some men are shut down and need opening, some men are open but process differently than therapy expects, and we need to distinguish between these cases instead of treating all male emotion as deficit.

I Don't Know

I started this piece by saying I don't know the answer.

Maybe I'm wrong. Maybe the emphasis on verbal vulnerability is correct for everyone and male resistance is just resistance to be overcome.

Maybe I'm right. Maybe therapeutic culture has been feminized in ways that pathologize male psychology and mistake one processing style for the only legitimate processing style.

Probably both contain truth. The male armor does hurt men. And the therapeutic framework often doesn't understand male psychology.

The question is worth holding. What if the way we've structured emotional health is gendered? What if the universalization of one style as virtue excludes people who process differently?

Brené Brown isn't wrong. Vulnerability matters. Shame corrodes.

But vulnerability as universal prescription, shame-talk as the only valid approach, emotional disclosure as the metric of health—this may be incomplete.

This may be a framework built by people who process one way, universalized to people who process differently, with the differences labeled as deficits.

Or maybe not. I genuinely don't know.

But I think the question is worth asking, even if I can't answer it.

Previous: The Divine Feminine Isnt the Opposite of Toxic Masculinity Next: Why Some Bi Men Just Stop Dating Women