Black Sails Is the Best Business Show Ever Made

Part 1 of 13 in the Black Sails: A Leadership Masterclass series.

Succession is about inheriting power. Black Sails is about building it—then watching it eat you alive.

I need you to understand something: a show about 18th-century pirates, produced by Michael Bay, airing on Starz between soft-core porn blocks, accidentally became the most sophisticated examination of startup dynamics, platform economics, and organizational failure ever filmed. Better than Billions. Better than Silicon Valley. Better than anything set in an actual office.

It just took four seasons for anyone to notice.

Here's the setup. Nassau, early 1700s. A self-governing community of criminals operating outside British law. No kings. No taxes. No rules except what the captains enforce.

It's a startup.

The pirates are founders. The ships are companies. The crews are employees who can vote out leadership at any time—actual democratic governance, centuries before corporate America pretended to invent it. The treasure is revenue. Nassau is the market. And the British Empire is the Fortune 500 competitor with unlimited runway who will eventually notice you exist.

Every business dynamic you've ever experienced plays out on these ships. But with swords. And consequences.

Succession is about the wrong thing.

The Roys are fighting over inheritance. Who gets the kingdom when the king dies. It's a medieval question dressed in helicopters. Compelling television, but the stakes are soft—worst case, you lose your money and have to be merely rich instead of obscenely rich.

Black Sails asks harder questions: How do you create something from nothing? How do you hold it together when the people who built it want different things? How do you survive when the empire finally looks your way?

The worst case in Black Sails is hanging. Or worse—watching everything you built get absorbed by the system you were trying to escape. The show understands that organizational death is often worse than physical death. At least the hanged man doesn't have to watch.

The cast is a taxonomy of power.

Captain Flint is the founder-visionary. Brilliant, driven, lying to everyone including himself about what the mission actually is. The pitch deck says "pirate republic" but the real motivation is revenge for a dead lover, and he'll sacrifice the entire crew to get it. Every startup founder who said "we're changing the world" while knowing runway was six months—that's Flint. The lie isn't a bug. The lie is how things get built.

Long John Silver is the operator who arrives with nothing and ends up running everything. No formal authority. No resources. No position. Just an understanding of how power actually moves that exceeds everyone around him. Silver doesn't want to be in charge—he wants to be comfortable—but his pattern recognition is so good that leadership keeps accreting to him by accident. The operator always inherits. The visionary always flames out. This is the show's darkest thesis and it's probably true.

Charles Vane is sovereignty as value. He will not bend. Not for money. Not for love. Not for survival. When the British offer him a deal—submit and live—he chooses the noose. Some people would rather die free than live managed. Vane is what happens when "I answer to no one" is the core operating principle. The show respects him. The show also kills him. Draw your own conclusions.

Eleanor Guthrie is platform power before platforms existed. She doesn't sail—she runs the port. Every pirate who takes a prize needs somewhere to sell it. Every ship that needs supplies needs her infrastructure. The pirates think they're the power because they have guns. Eleanor knows she's the power because she has the choke point. She's AWS. She's the App Store. She's what happens when you control the layer that everything else depends on. Her tragedy is that she trades platform power for institutional power—tries to legitimize by marrying into the British system—and loses everything. Platforms are powerful until they want to be something else.

Max starts in a brothel. Not as owner—as merchandise. Exploited, abused, sold. The lowest position a woman could occupy in Nassau's economy. She ends the series running that economy. No sword. No ship. No inheritance. Just leverage, timing, and the willingness to do what others wouldn't. Max is the only character who actually wins. That should tell you something about what winning requires.

Jack Rackham isn't the best pirate. Isn't the best fighter. Isn't the best anything. But he's the one telling the story—and when the smoke clears, the narrator is the one who decides what it meant. Narrative control beats operational control. The writer outlasts the warriors. Jack Rackham is a lesson for anyone who thinks execution is everything.

The show understands something about lies that most business content won't admit.

Flint lies constantly. To the crew about the prize. To his partners about the plan. To himself about the reasons. The lies aren't weakness—they're technology. Leadership technology.

The men can't handle the truth. The truth is that this is Flint's personal vendetta against an empire that destroyed someone he loved. The truth is that the pirate republic is a means to an end that only Flint cares about. The truth is that most of them will die for a cause they don't understand.

So Flint tells them stories. The treasure. The freedom. The republic. Stories they can fight for.

Every founder does this. The pitch deck isn't the truth—it's the story that makes the truth achievable. The vision isn't real yet—it's the story that might make it real. The mission statement isn't what the company does—it's what the company needs to believe about itself to do anything at all.

Flint is just more honest about being dishonest. Or more dishonest about being honest. The show never tells you which.

Then they get the gold.

The Urca de Lima. Spanish treasure galleon. Five million dollars. The prize Flint has been chasing since episode one. The treasure that's supposed to change everything, fund the war, secure the republic, make it all worth it.

They get it.

And then nothing changes. Or rather—everything changes, but in the wrong direction.

The gold creates new problems. How to move it. How to protect it. Who controls it. The treasure that was supposed to be the solution becomes a new category of crisis. The coalition that held together while chasing the gold fractures the moment they have to decide what to do with it.

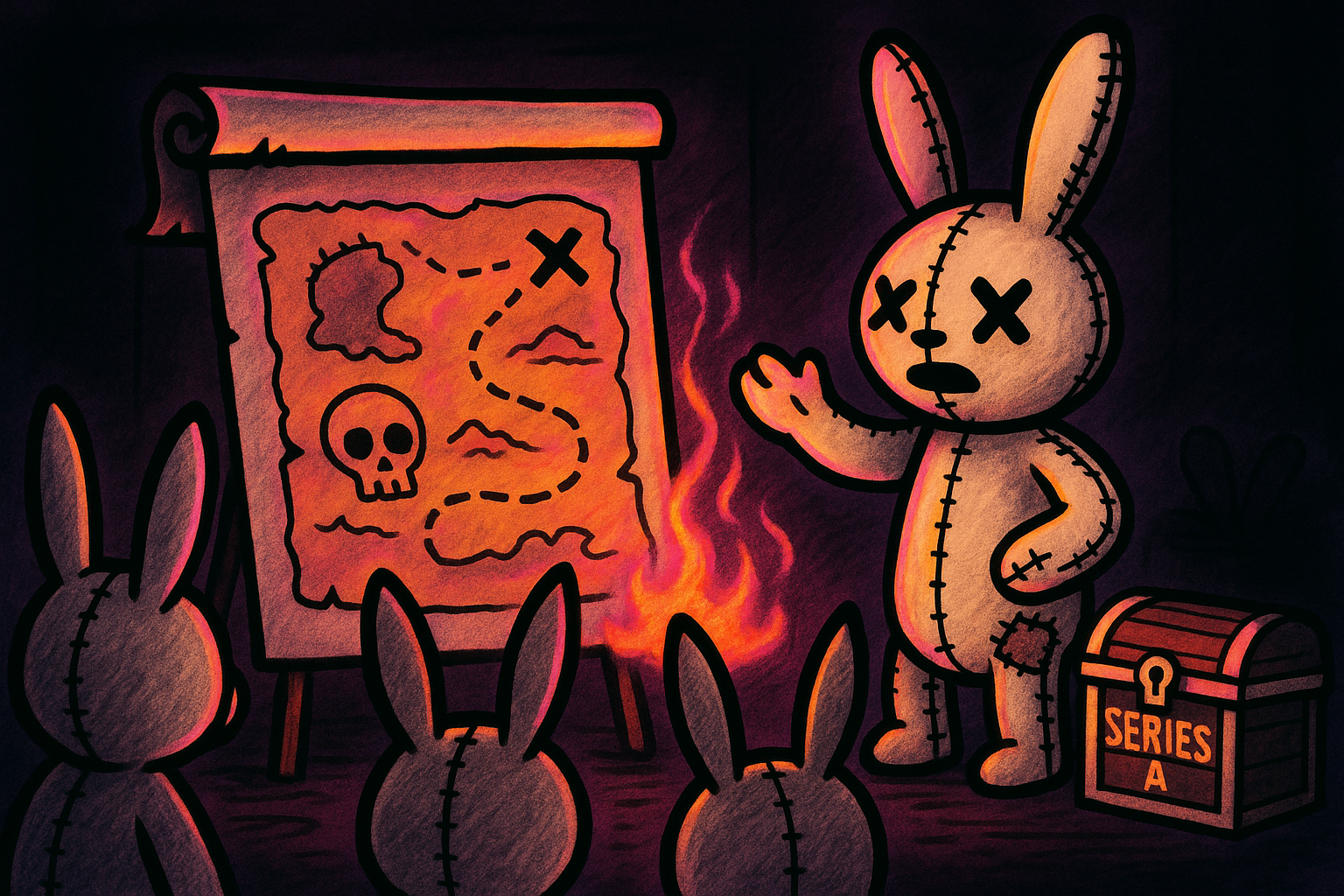

This is product-market fit. This is closing your Series A. This is the acquisition offer. The thing you were chasing was supposed to be the answer. You get it, and you discover the hard part was just beginning.

The Urca gold doesn't save the pirate republic. It accelerates the conflicts that destroy it.

Peter Turchin would recognize Nassau immediately.

His theory of elite overproduction: societies destabilize when they produce more elites than there are elite positions. Too many princes fighting for one throne. Too many lawyers competing for too few partnerships. Too many MBAs chasing too few corner offices.

Nassau is elite overproduction in miniature.

Too many captains. Not enough ships. Too many men who see themselves as protagonists. Not enough roles for them to play. Everyone has tasted freedom, tasted power, tasted being somebody. No one wants to go back to being nobody.

When everyone's an alpha, violence is the only sorting mechanism.

The show watches this play out across four seasons. Captains killing captains. Alliances forming and breaking. The talented destroying each other because the ecosystem can't support them all. It's also every startup ecosystem you've ever seen. Every VC-funded cohort with more founders than exits. Every industry with too many players chasing too little profit pool.

The overproduction must resolve. The resolution is rarely gentle.

The pirate republic falls.

This isn't a spoiler. It's history. Nassau was reclaimed by the British. The pirates were hanged or pardoned into submission. The dream of a free society outside imperial control lasted less than a generation.

The show is a meditation on why. Why freedom projects fail. Why communes collapse. Why startups that swore they'd stay cool become bureaucracies. Why every revolution ends in new tyrannies.

The reasons are structural:

The empire eventually notices. You can only operate in the margins while the giants are distracted. Eventually they look your way. They have more resources, more patience, more legitimacy. They will wait you out, buy you out, or crush you. There is no fourth option.

Internal conflict compounds. Without external structure, internal structure must be negotiated constantly. Every decision is a fight. Every fight drains energy. The resources that should go to building go to governing. You can't outrun this.

The founders want different things. Flint wants revenge. Silver wants safety. Vane wants sovereignty. Eleanor wants power. They're all building "the pirate republic"—but they're not building the same thing. The divergence is invisible until it's fatal.

Success changes the equation. Getting what you wanted doesn't end the story. The scrappy insurgent becomes the defender of something. Defending is a different game than attacking. Most founders can't make the transition.

The ruthless outlast the principled. People who will do anything have an advantage over people who won't. Eventually someone is willing to do what others aren't. They win. They're not who you wanted to win.

The operator inherits.

Silver ends the show having outmaneuvered everyone. Not through fighting—though he can fight. Not through vision—he has none. Not through resources—he started with nothing.

Through reading the room.

Silver understands power the way some people understand mathematics. He sees the moves before they happen. He knows what everyone wants, what they'll do to get it, what they'll sacrifice to avoid losing it. He doesn't need to be the most powerful person in the room. He needs to be the person who understands the room best.

The visionaries flame out. The warriors die. The platforms get captured. The operator adapts.

This is the show's dark thesis about leadership: the visionary is necessary to start things. But the visionary doesn't survive them.

Watch it again.

If you saw Black Sails for the ships and swords, you missed it. Go back. Watch Flint's noble lies. Watch Silver's ascent. Watch Eleanor's platform play. Watch Max's impossible climb from the bottom. Watch the elite overproduction cycle grind through Nassau. Watch the freedom project fail in exactly the ways freedom projects always fail.

It's the most honest leadership content ever filmed.

It just happens to be about pirates.

Previous: Black Sails: A Leadership Masterclass Disguised as Pirate TV Next: Captain Flint: The Founder Who Lies for the Mission