Beginners Feel Like Experts

Why the less you know, the more confident you are. Explore the Dunning-Kruger effect, calibration problems, and why real expertise feels like doubt instead of certainty.

Why the less you know, the more confident you are—and why real expertise feels like doubt

You watch a few YouTube videos on investing. Now you see the market clearly. These patterns are obvious. Why doesn’t everyone just do this? You’re ready to trade.

Six months later, after the market has humiliated you, you realize you knew nothing. The patterns weren’t patterns. The clarity was an illusion. You were confidently incompetent.

Welcome to Mount Stupid. Population: everyone who’s ever started learning anything.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect

The Dunning-Kruger effect is the tendency for people with low ability to overestimate their competence, while people with high ability underestimate theirs.

It’s often summarized as “stupid people don’t know they’re stupid.” But that’s wrong, and kind of mean.

The real finding is more interesting: everyone is bad at estimating their own competence, but the direction of the error depends on where you are in the learning curve.

At the beginning, you overestimate. You don’t know what you don’t know. The territory looks simple because you can’t see the complexity yet.

As you advance, you start to see how much there is to know. The more you learn, the more gaps you discover. Confidence drops. You might even feel less competent than when you started.

If you keep going, you eventually reach actual expertise. But by then, you’re aware of how hard it is. You assume others must find it this hard too—so you underestimate your relative ability.

The result is a confidence curve that doesn’t match the competence curve. Beginners feel like experts. Experts feel like beginners.

The Geography of Competence

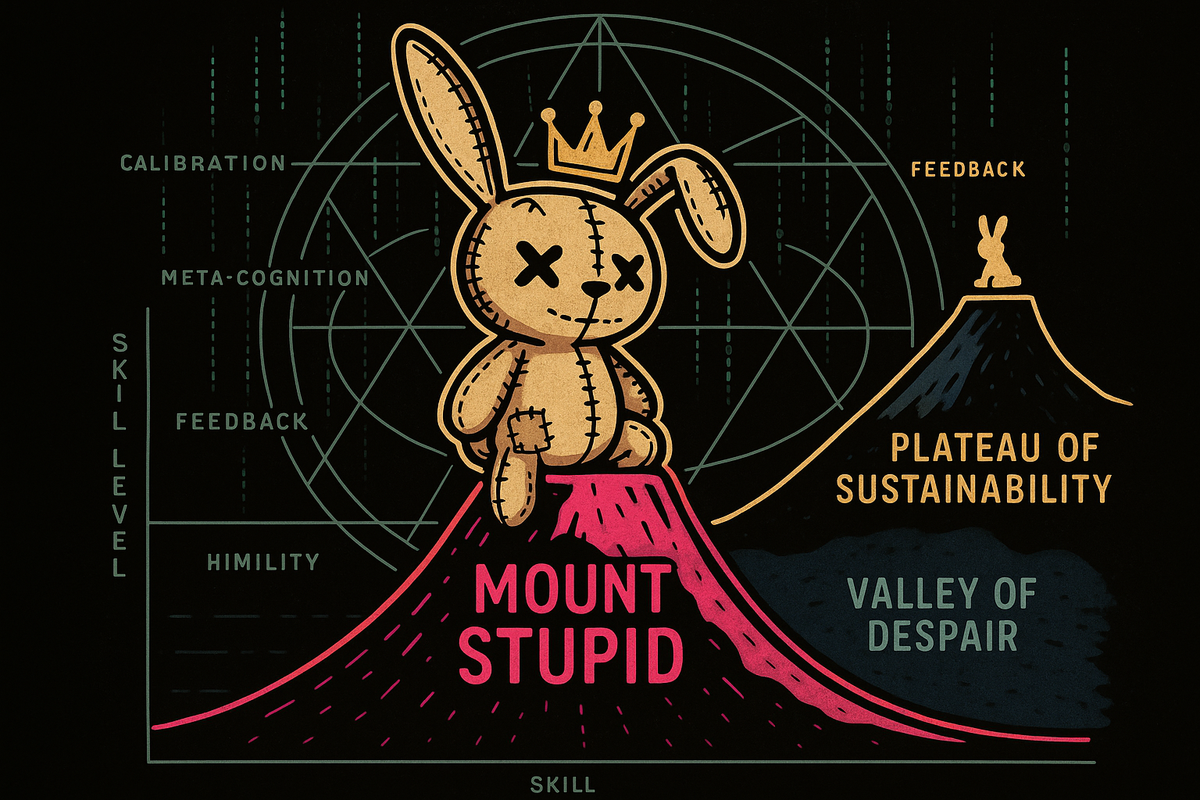

The popular image is a curve with named landmarks:

Mount Stupid (peak of confidence, minimal competence): You’ve just learned enough to think you understand. The YouTube videos made it seem simple. You’re confident because you can’t see what you’re missing.

Valley of Despair (low confidence, growing competence): You’ve learned enough to realize how much you don’t know. The more you study, the more gaps appear. You feel less competent than before, even though you’re actually more competent.

Slope of Enlightenment (rising confidence, rising competence): You’re building real skill, and your confidence starts to calibrate. You still see gaps, but you also see that you can fill them.

Plateau of Sustainability (calibrated confidence, high competence): Real expertise. You know what you know, you know what you don’t, and your self-assessment is fairly accurate.

Most people never get past Mount Stupid. They learn just enough to feel confident, encounter no serious challenge, and remain confidently incorrect forever.

Why It Happens

The Dunning-Kruger effect is a calibration problem.

Calibration means your confidence matches your accuracy. Well-calibrated people are confident when they’re right and uncertain when they’re wrong.

Calibration requires feedback. You need to make predictions, see outcomes, and update your confidence accordingly. This is how you learn how much your intuitions can be trusted.

The problem: feedback is often missing, delayed, or ambiguous.

The novice investor sees their first successful trade and feels validated. They don’t see the other possible outcomes. They don’t have enough trials to distinguish luck from skill. Their feedback is noisy and sparse.

The expert has thousands of data points. They’ve been wrong many times. They’ve seen how complex the domain really is. Their feedback is dense and humbling.

Dunning-Kruger isn’t about intelligence. It’s about exposure. Beginners are poorly calibrated because they haven’t accumulated enough evidence to know the limits of their knowledge.

The Meta-Cognition Problem

Here’s the deeper issue: the skills needed to assess competence are the same skills needed to be competent.

To know you’re bad at chess, you have to be good enough at chess to recognize bad play. If you can’t recognize a blunder, you can’t recognize that you’re blundering.

To know you don’t understand economics, you have to understand enough economics to see the gaps in your understanding. If you don’t know what you’re missing, you can’t feel the absence.

This is why Dunning-Kruger is so pernicious. The very incompetence that leads to poor performance also leads to poor self-assessment. The bug is protecting itself.

Where This Costs You

Intellectual humility. After reading one book on a topic, you feel equipped to argue with experts who’ve spent decades in the field. The book gave you vocabulary and a few ideas. It didn’t give you the ten thousand hours of edge cases, failures, and complications that constitute real understanding.

Career decisions. You’re confident you can do the job you’ve never done. Maybe you can. But your confidence isn’t evidence—it’s just Dunning-Kruger. The job looks simple from outside. It probably isn’t.

Advice-giving. The less you know, the more certain your advice. Beginners give confident recommendations. Experts hedge, qualify, say “it depends.” If someone is certain about a complex topic, they might be on Mount Stupid.

Learning plateaus. Overconfidence kills curiosity. If you already understand, why keep studying? Mount Stupid is where self-directed learning often stops.

Hiring and evaluation. Confident candidates seem more competent. But confidence at interview might be Dunning-Kruger, while the uncertain candidate might have deeper knowledge and better calibration.

The Irony for Experts

The flip side hurts too. Experts underestimate their ability.

When you’ve worked in a domain for years, the knowledge feels obvious. Surely everyone knows this. You’ve forgotten what it was like not to know. The curse of knowledge: you can’t reconstruct your beginner’s mind.

So you undervalue your expertise. You assume others are as capable. You don’t charge enough, advocate enough, or claim the authority you’ve earned.

Dunning-Kruger cuts both ways. The beginner is overconfident. The expert is under-confident. Somewhere in between is the sweet spot of accurate self-assessment.

The Move

Calibration is a skill. You can get better at it.

Track predictions. When you form a confident opinion, write it down with your confidence level. Check back later. Over time, you’ll learn where your confidence is calibrated and where it overshoots.

Seek disconfirmation. Confidence is self-reinforcing. You look for evidence that supports your view and interpret ambiguous evidence charitably. Deliberately seek information that might prove you wrong.

Ask experts for the gaps. When you think you understand something, ask someone who’s been in the field longer: “What am I missing? What do beginners usually get wrong?” Their answer will reveal complexity you couldn’t see.

Update on being wrong. Every time you’re wrong, it’s calibration data. Not a failure—a correction. Over time, these corrections drag your confidence curve toward reality.

Assume you’re on Mount Stupid. In any domain where you’re not extensively experienced, default to the assumption that you’re missing something. The feeling of understanding is not evidence of understanding.

The Dunning-Kruger effect isn’t about stupidity. It’s about the structure of learning. Early knowledge brings false confidence. Real competence brings appropriate humility.

If you feel like you’ve got it all figured out, you probably don’t.

And if you feel like you’ll never understand, you’re probably further along than you think.

This is Part 11 of Your Brain’s Cheat Codes, a series on the mental shortcuts that mostly work—and the specific situations where they’ll ruin you.

Previous: Part 10: They’re Lazy vs. Traffic Was Bad

Next: Part 12: The Shortcut Barbell — Integration