The Avocado Toast Math Is Actually Correct

The Avocado Toast Math Is Actually Correct

"If millennials stopped buying avocado toast and lattes, they could afford a house."

You've heard this. It's become a meme, a punchline, a symbol of boomer-millennial culture war. The usual response is to point out that skipping $15/day doesn't add up to a $400,000 house.

But here's the thing: the kids doing the math aren't wrong. They're actually doing better math than the people criticizing them.

They're just using a different model of how wealth works. And their model might be more accurate.

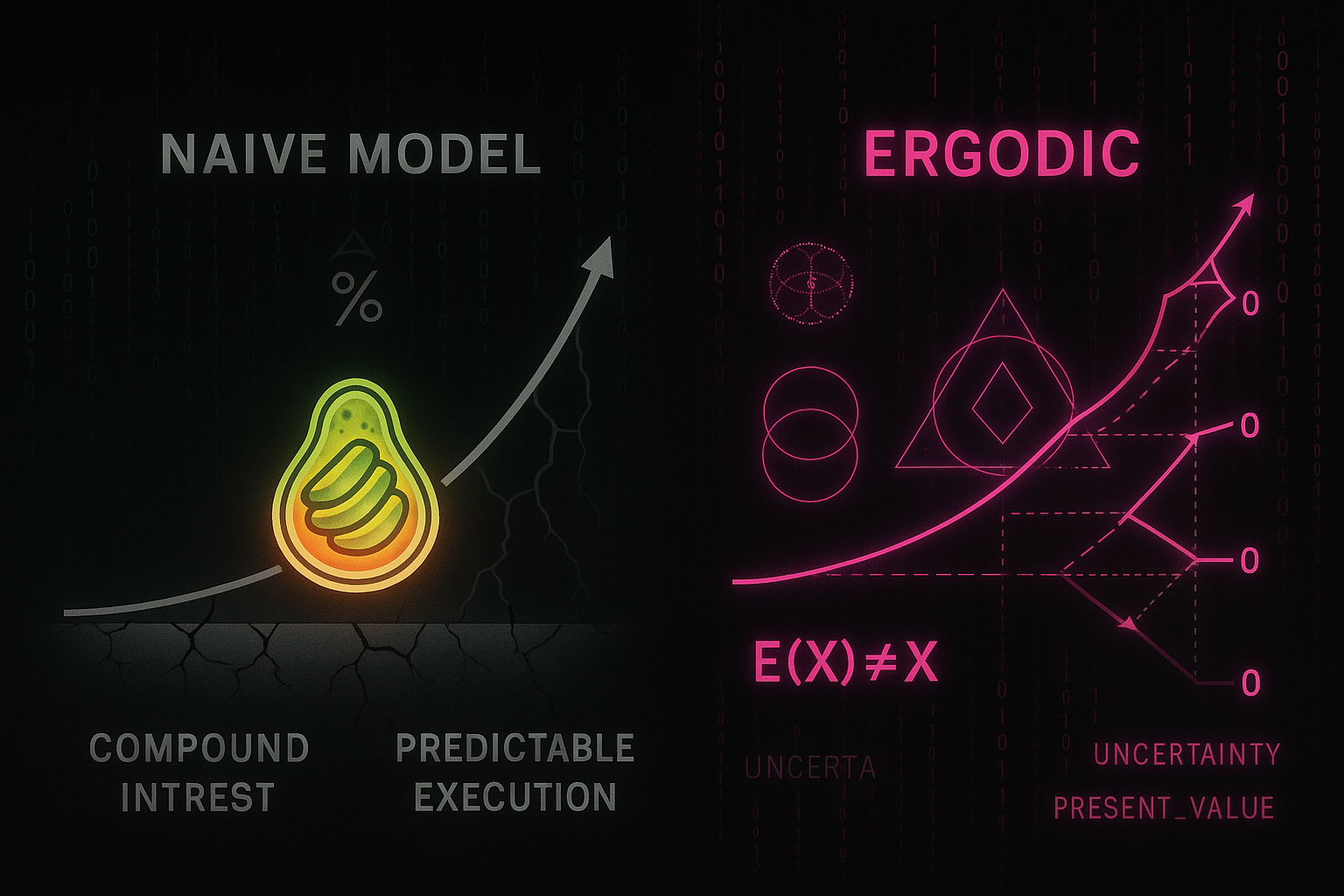

The Compounding Myth

The standard financial advice goes like this: small savings compound over time. Save $5/day, invest it at 7% annual returns, and in 40 years you'll have... a lot of money. The math is technically correct.

But the math assumes things that aren't true anymore:

Assumption 1: Stable, predictable returns. The 7% figure comes from historical stock market averages. But averages hide volatility. And volatility matters more when you're a single person than when you're a statistical average. You don't live a thousand lives; you live one. A market crash at the wrong time wipes out decades of compounding.

Assumption 2: Stable currency value. Compound interest calculations assume dollars in 2065 are worth something predictable relative to dollars today. But inflation is variable, monetary policy is increasingly experimental, and nobody actually knows what purchasing power looks like in 40 years.

Assumption 3: Stable employment. The "save consistently for 40 years" model assumes you'll have income consistently for 40 years. In a gig economy with frequent job changes, industry disruptions, and no guaranteed pensions, that's a big assumption.

Assumption 4: Housing prices stay accessible. The whole "save for a house" framing assumes house prices don't outpace your savings rate. In most major metros, they have. For decades.

The kids look at these assumptions and notice they don't hold. The response isn't financial irresponsibility. It's epistemic accuracy.

Ergodicity: The Concept That Changes Everything

Here's where it gets technical, but stay with me because this is the key.

Standard financial math treats you as if you were the average of many people. If 1,000 people invest in the stock market and the average return is 7%, you're supposed to expect 7%.

But you're not 1,000 people. You're one person. And what happens to you specifically matters more than what happens on average.

This is called ergodicity, and it's the concept that separates naive financial thinking from sophisticated financial thinking.

A game is ergodic if the time-average (what happens to one person over many periods) equals the ensemble average (what happens to many people in one period). Most financial instruments are not ergodic. The average outcome across many people doesn't predict your outcome as one person over time.

Example: Russian roulette with a million dollars. Five chambers empty, one loaded. If 6 people play once each, on average they make $833,333. Great expected value! But if one person plays 6 times, they're dead. Same "average," completely different outcome.

Your kid intuits this. They see people who did everything right—saved, invested, followed the rules—get wiped out by a medical bill, a market crash, a job loss. They see that the "average" outcome isn't available to any individual person, just to statistical aggregates.

So they buy the avocado toast. Because optimizing for a future that might not arrive the way the models predict is a bad bet.

Present-Orientation as Rational Strategy

Under uncertainty, optimal strategy changes.

When the future is predictable, you optimize for it. You sacrifice now for later. This works when "later" looks roughly like you expect.

When the future is unpredictable, present-orientation becomes more rational. You extract value now because you can't be sure the value will be available later.

This isn't shortsightedness. It's time-horizon calibration under uncertainty.

Your parents could reasonably expect that saving for a house would result in owning a house. The relationship between behavior and outcome was legible.

Your kid looks at housing prices, wage stagnation, climate instability, political volatility, and thinks: "The relationship between saving now and security later is much less clear."

That's not irresponsibility. That's probability assessment.

The Consumption-as-Investment Move

Here's another angle the critics miss: some consumption is investment.

The latte your kid buys at the coffee shop might be where they:

- Work on their side project

- Have the conversation that leads to a job opportunity

- Maintain the social connection that becomes their support network

- Rest enough to perform well at work

The avocado toast brunch might be:

- Social capital maintenance

- Mental health investment

- Network development

- Actually enjoying life, which turns out to matter

The "cut all consumption" model treats every dollar spent as purely lost. But humans aren't just financial optimizers. We're social animals who need connection, experience, and yes, pleasure to function well.

The kid spending $15 on brunch instead of putting it in an index fund might be making a better investment. Just not one that shows up in a brokerage account.

What the Boomers Had

Let's be honest about what previous generations had that made "sacrifice now, save for later" actually work:

- Pensions. Actual guaranteed retirement income, not "hope the market doesn't crash when you're 68."

- Affordable housing relative to income. The house-to-income ratio has roughly tripled since the 1970s.

- Stable employment. Jobs that lasted decades at companies that didn't disappear.

- Lower education costs. College that could be paid for with a summer job.

- Healthcare that didn't bankrupt you. Before a single medical event could wipe out a lifetime of savings.

The "just save more" advice assumes the infrastructure that made saving work still exists. For many young people, it doesn't.

They're not failing to save. They're correctly assessing that the savings-to-security pipeline is broken.

The Reframe

Your kid's financial intuitions might be better than yours.

They're operating with an implicit understanding that:

- The future is less predictable than models assume

- Individual outcomes diverge from averages

- Present value is certain while future value is probabilistic

- Social capital is real capital

- Enjoying life isn't a bug in the optimization function

This isn't financial nihilism. It's ergodic reasoning applied to household economics.

The avocado toast isn't the problem. The problem is a set of economic assumptions that haven't updated to match reality.

Your kid did the math. They just used better variables.

This is Part 6 of the Kids Are Alright series. Next: "Disorder Is Relative to Environment."